An ‘epic’ discussion about the Philippines’ wealth of long narrative poems

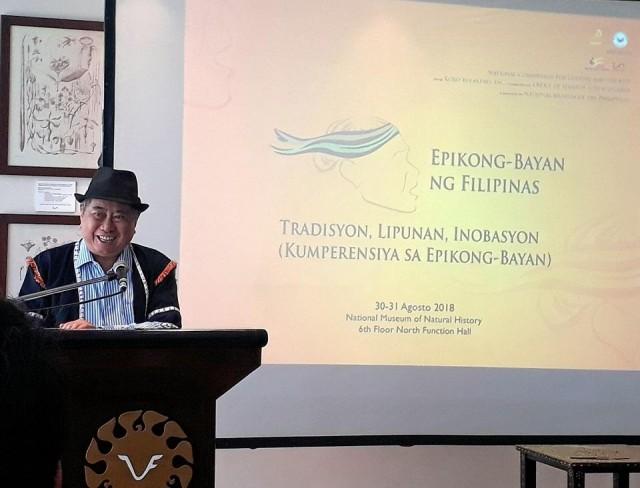

It was expected to bring in only about a hundred participants, but the students, teachers, and school administrators from all over the country who showed up to the Epikong-Bayan ng Filipinas: Tradisyon, Lipunan, Inobasyon conference at the National Museum of Natural History in Manila last week were nearly double that number.

Among them was a 50-year-old English teacher from Central Luzon who attested, during an open forum, that Biag ni Lam-ang is the national epic of the Philippines.

While the statement was carried out as an honest inquiry, it stirred up a hornet’s nest. Even more so as cultural workers and leaders of indigenous peoples’ communities were present at the conference.

The question gave the participants a glimpse of how pitiable the educational system is. Not lagging behind is another problematic detail in textbooks for decades: lack of knowledge about who authored Biag ni Lam-ang.

Placing Pedro Bucaneg

In his opening remarks, National Artist for Literature and National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) Chairman Dr. Virgilio Almario asked the participants who among them knew who Pedro Bucaneg was.

Bucaneg was an Ilocano poet who lived in the 17th century.

Expressing his frustration that majority have not heard about Bucaneg, Almario noted, “Sa epikong-bayan na lamang, tuwing nagsasalita ako sa mga kumperensiya ng titser, sabi ko, ‘Alam ba ninyo na mayroon tayong mahigit nang 50 na recorded na epikong bayan?’ Siyempre ang sagot nila, ‘Hindi po.’”

It was unfortunate, he said, that teachers could only mention five of them, including Biag ni Lam-ang, Hudhud, and Darangën.

“Doon nga sa Cordillera nung minsan tinanong ko kung sino ang bida sa Hudhud, nagtinginan sa malayo ang mga titser,” Almario said, relating that that the teachers only knew the title of Hudhud, but were not aware of its story.

“Ipinagmamalaki natin na tayo ay mayroong rich and diverse cultural heritage. Pero hindi natin natatamasa dahil hindi natin alam. Kaya napakahalaga na sa ating pag-uusap ngayon ay magsimula tayo talaga na seryosohin hindi lamang ang pag-uusap, kundi ang pagsasaliksik, pagkakaroon ng dagdag na kaalaman, at pag-iisip din kung paanong ang ating kaalaman ay ma-popularize.”

Almario’s speech, entitled “Kung Bakit Mahalaga si Pedro Bucaneg,” began with E. Arsenio Manuel’s 1962 lecture at Indiana University, which he believes was the first comprehensive study of folk epics in the country.

At the end of Manuel’s long lecture, he emphasized the need for a planned research program, which we lack to this day.

“Ang ating ginagawa, simula lamang para talaga tayo makabuo ng isang research agenda hindi lamang sa ating epikong-bayan, kundi tungkol sa ating cultural heritage. Napakalaking bagay ang nawawala sa atin kapag hindi natin dinibdib, hindi natin sineryoso, ang pagsasaliksik tungkol sa ating intangible cultural heritage.”

Doing research on folk epics and folk literature, in general, is not only the task of Manuel and other scholars.

“Napakababaw ng ugat natin sa nakaraan at iyon ay dahil kakaunti ang alam natin sa nakaraan. Kailangang palalim natin ang ating kaalaman sapagkat nakasalalay doon ang ating pangarap na higit nating makikilala ang ating sarili.”

In Almario’s speech, he noted that Manuel did not acknowledge Bucaneg’s work since “naganap ang pinakaunang rekording ng Biag ni Lam-ang noong 1889 nang ilathala ito ni Isabelo de los Reyes sa kaniyang peryodikong El Ilocano batay sa isang nakasulat na tekstong ipinadala ni Fr. Gerardo Blanco mulang Bangar, La Union.”

Manuel also identified the long narrative poems as “folk epics” and “ethnoepics,” in order to separate them from the known literary “epics,” like the Iliad and Odyssey. It was this reason, according to Almario, that the translation “epikong-bayan” was derived for the conference.

Naming the ethnoepics

Dr. Rosario Cruz-Lucero, who delivered her lecture “Pagbasa ng Epiko Bilang Anyong Pampanitikan: Isang Panimulang Poetika,” said that one of the concerns of the Departmento ng Filipino at Panitikan ng Pilipinas, where she teaches at University of the Philippines (UP), Diliman, was the term “epiko.”

“Gusto sana naming iwasan iyong katagang ‘epiko’ [in referring to our ethnoepics, collectively] kasi tunay natin itong katutubong panitikan. So mayroong mga nagsabing Ulahingan na lang [ang itawag]. Eh siyempre mayroon ding mga taga-Panay bakit hindi Suguidanon,” she related.

Lucero asked the participants to help the academe with this endeavor.

“Ang epiko kasi napakabanyagang salita samantalang ang dami nating pangalan para dito na talagang sa buong kapuluan may commonality. Lahat ng mga ito. [Epiko] ang pinakamasasabing pinaka-national literary form natin. Pati ang konsepto ng bansa, ng nasyon, lumalabas,” she expounded.

National Artist for Music Dr. Ramon P. Santos, who lectured on “Mga Katinigan sa mga Epiko sa Pilipinas,” explained that the word ulahing, for the Manobo ethnoepic Ulahingan, is a style of language and music. He also mentioned that the word ullalim is a generic term for the ethnoepic of the Kalinga people.

Pagsusugid was mentioned by Dr. Maria Christine Muyco, whose lecture was “Ang Limog sa Suguidanon (Epiko ng Panay Bukidnon).” The Kinaray-a word sugid is a generic term which means “to tell.”

Following such reason, suguidanon is a collective generic term for the ethnoepics of Panay. It was the center of Dr. Alicia Magos’s research, which she discussed in her lecture “Ang Epikong Bayan ng Panay Bukidnon.”

Magos was the chief researcher and senior translator for the book Tikum Kadlum (“Enchanted Black Hunting Dog”), the first of a series of books on the 10 epics of Panay Bukidnon, published by UP Press. In 2014, the book received National Book Award for Poetry Category (Hiligaynon/Kinaray-a) from the National Book Development Board and Manila Critic’s Circle.

The suguidanon in 13 volumes was a product of more than two decades of research of Magos, with Anna Razel Ramirez and Eliodoro Dimzon as Project Leaders.

With her lecture “In Search for the Epics of Panay (Panay Epics: Galing sa Pagtuklas hanggang sa Paglimbag at ang Kategorya,” Ramirez sat on the same panel with Magos, discussing the ethnoepics of the Visayan region. While Randy Madrid, another mentee of Magos, lectured on “Mula Ligbok Tungong Hinilawod at Sugidanon: Tradisyon at Inobasyon sa Teksto ng Epikong Panayanon.”

Meanwhile, a History professor at a university in Manila suggested the term “guman.” Another participant, a local official from South Cotabato who claimed he once had a copy of the ethnoepic Indarapatra at Sulayman, revealed that guman, in the Visayan language, means “hindi napuputol ang sinasabi.” It was derived from the word goma (“rubber”).

Guman was part of Ivie Carbon Esteban’s lecture “Re(articulating) Contemporaneity and Dliyagen Cycle: The Subanën Gingguman as Text.”

Esteban explained that, “among the Subanën [people] in the Zamboanga Peninsula, Western Mindanao, the term guman refers to a long narrative of their ancestors who once lived in a kingdom along a mighty and majestic river.” The act of singing, chanting or narrating the guman is called ginggumanen.

Timothy Ong, whose lecture was “The Folk Anthologist and the Philippine Literary Tradition,” also headed for the local collective term for our ethnoepics.

Ong pointed out that although anthology, as a genre, is a text constituted by several smaller, individual texts, it is forced to assume homogeneity.

Because of the nature of the ethnoepics’ orality, he suggested the term “salimbibig,” to transmit from one’s mouth to another’s, as to breathe life into something. He likened it to what Mojares referred to as the Malay nyawa or “breath” and the Greek anima or anemos or “wind.”

“Sa pagbuka ng bibig,” Muyco brought up the term ginhawa. In the sugidanon, hawa was connected to “espasyo/ispirito/hangin.”

Dr. Rosario del Rosario from UP Diliman’s College of Social Work and Community Development, also expressed hesitation in using the term “epic.”

According to del Rosario, American folklore scholar Munro Edmonson had already pointed out in 1971 that the long narratives of Southeast Asia, Indonesia, and the Philippines should not be referred to as “epics.” They are not epics, but “near-epics.”

Lecturing on Philippine Epics of Luzon, del Rosario focused on the Hudhud of the Ifugao people in Northern Luzon. She pointed out that the Ifugao people had no “epic,” just hudhud. Hudhud, she said, is the name of the genre.

Women’s place

It is easy to spot that there are more female lecturers than their counterparts. Dr. Felicidad Prudente lectured on “Ang Pag-awit ng Gasumbi ng mga Buaya Kalinga ng Hilagang Luzon: Paglalarawan, Himig, at Damdamin” and Jonalyn Villarosa on “Pagpapayabong ng Panitikan: Isang Masusing Pag-aaral sa Pala’isgen, ang Epiko ng mga Tagbanwa.”

Del Rosario, whose lecture was a rework of her paper “A Gender Reading of the Ifugao Hudhud of Dinulawan and Bugan at Gondahan, Translated by Lambrecht,” disclosed that she always looks at gender.

Folklorists, she said, have noted the lack of heroines in epics. This was in contrast with what Tanzanian folklorist Joseph Mbele’s observation that “women characters play various roles in African epics, including heroic roles.”

“Audiences and scholars generally fail to note and appreciate the full extent of these roles, focusing instead, on male characters and their actions. Thus, notions such as heroism are seen and understood from a male perspective,” del Rosario explained.

The Ifugao hudhud is not about male heroic struggles. According to del Rosario, “It is about women’s extraordinary struggles in the violent world, where women play the most decisive roles equal to men’s battle skills.”

The hudhud, she asserted, is a representation of a female world view, in which the mother and the maternal brother are prominent, and in which fathers are in the background.

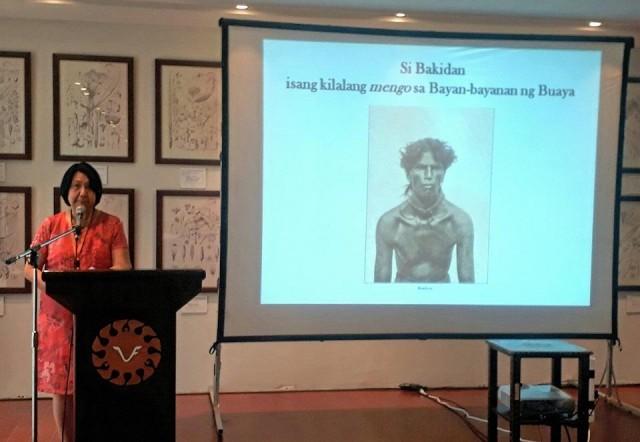

Prudente also placed the heroic role of women in ethnoepics. In her lecture, she explained that aside from the Ullalim, the Kalinga people also have the ethnoepic Gasumbi.

The latter narrates the heroic and extravagant life of Gawan, a mengo (“headhunter”). But according to Prudente, one part of Gasumbi narrates the adventure of five women headhunters, lead by Gammelayan.

Lucero also noted the deliberate gender bias of the colonizers, when the serpent Oryol was referred to as female when the Bikol ethnoepic Ibalong was transcribed and translated into Spanish in the 19th century.

The Bikol languages do not have grammatical gender classifications of the Spanish language.

Revaluing our ethnoepics

As the sessions progressed, it was established that the ethnoepics from different parts of the country constitute the collective literature of the nation.

In her lecture, “Oral Epics in a Cultural Context,” Maria Stanyukovich of the Russian Academy of Science, compared the ethnoepics to musical instruments. It could be as long as the period of waiting for relatives to arrive at a funeral, or chanting the many battles fought by the heroes. Sometimes, it is made short by natural disasters like flood and earthquake, or by a pastor who will rebuke it as an instrument of the devil.

Like the bulos in Madrid’s lecture, ethnoepics can be whole epics or epics comprised of many episodes. Also, as Magos related, “Kung gaano katagal ang epiko mas maraming versions.”

In Eufracio Abaya’s lecture “Ang Epiko Bilang Kaalamang-Bayan: Sa Pananaw nina Isabelo de los Reyes, E. Arsenio Manuel at Damiana Eugenio,” he recalled the folklorists’ role in history and the promotion of folklore studies.

Scholars also offered frameworks in the study of ethnoepics, like Hobart Savior’s lecture “Ulaging: Pagka Bihag Ta Nalandangan and the Agpangan–Gantangan–Timbangan Cultural Framework” and Esteban’s Conceptual Framework of Ethno-epics as Texts and Comparative Framework of the Epic Variants.

But Lucero pointed out that although most people have high regards for our ethnoepics, it is ironic that they try to avoid it. In her lecture, she showed how the themes and characters of our local telenovelas and movies are similar to those of our ethnoepics.

Meanwhile, Villarosa presented a module on how she taught Pala’isgen to university students in Palawan. LaVerne Dela Peña, whose lecture was “Ang Tradisyon ng Hudhud sa Hingyon, Ifugao,” made use of diagrams to make the hudhud more accessible to millennials.

Filmmaker Alvin Yapan (“Ang Bisa ng Pag-uulit sa Biswal na Naratibo”) and dramaturg Rodolfo Vera (“Ang Pagsasadula ng mga Epikong-Bayan sa Kasalukuyang Dulang Filipino”) related how they appropriated various ethnoepics into films and plays.

In his lecture “Ang Estruktura ng Kamalyang Nakapaloob sa mga Epikong Filipino,” former NCCA chairman Felipe de Leon, Jr. noted that we have to find the spiritual meaning in everything that we do. Creativity, he said, is something intrinsic.

In closing, Dr. Elena Mirano felt the need for cultural leaders to come together and surface the strong national agenda for the ethnoepic.

The epic has a cyclic life, Mirano explained. We see it in our life everyday. It is important that the voices are heard very clearly.

“What is our connection to the nation? Do you revalue epic to place it in the national? How do you get it to the educational system?” she said.

Participants were also able to experience the ethnoepics live through the performance of the chanters.

On the first day, Delfin Sallidao chanted a part of Ullalim of the Majukayong Tribe of Mountain Province.

Romulo Caballero, arbiter and barangay chieftain of the Masaroy Village in Calinog, Iloilo, and Rolinda Gilbaliga, a former student of the School for Living Tradition in Barangay Garangan, Calinog, Iloilo, both chanted parts of Sugidanon (Amburukay).

The next day saw Bai Florena Saway of the Talaandig community chant a part of Ang Pagsubok kay Agyu (Ulaging).

Rosie Sula, who is considered as the best T’boli chanter in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato, chanted a part of Tudbulul.

Subanën leader Nilda Mangilay chanted a part of Gingguman.

And Mëranaw onor of Lanaw Sinar Capal, also known as Potri Sinaraulan, chanted Paganay Kiyandatu sa Bumbaran from Darangën.

The conference, which was held on August 30-31, was organized by the NCCA, through Koro Bulakeño, Inc., with the Office of Senator Loren Legarda and the National Museum as partners. — BM, GMA News