Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Film review: Return of the king: Manuel Conde's 'Genghis Khan'

%20surveys%20his%20kingdom%20with%20Lei%20Hai%20(Elvira%20Reyes)%20by%20his%20side.jpg)

Genghis Khan (Manuel Conde) surveys his kingdom with Lei Hai (Elvira Reyes) by his side

"Good Lord, it’s a masterpiece!"

—James Agee, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, poet and film critic, speaking on Manuel Conde's "Genghis Khan"

Sixty years after wowing critics and fellow filmmakers alike at the Venice and Cannes Film Festivals, Manuel Conde’s 1950 masterpiece, “Genghis Khan,” has returned to the Philippines in the form of a brand-new, high-definition digital edition, meticulously restored from badly-damaged prints discovered in Italy, France and the UK.

The screening was the result of nearly a year’s work and collaboration between the Film Development Council of the Philippines and the newly-established National Film Archive of the Philippines, working in tandem with the Venice Film Festival and L’Immagine Ritrovata (which performed the actual restoration). President Benigno S. Aquino III was on hand for the formal repatriation ceremony which took place at the Philippine premiere of the new edition on Sept. 29.

“Genghis Khan” tells the story of Temujin (Conde, who also wrote and directed), a young Mongol prince who takes part in a series of challenges against rival tribes for land rights. Under the auspices of Burchou (Lou Salvador) and his beautiful daughter, Lei Hai (Elvira Reyes), Temujin uses his wits to prevail against larger, stronger opponents to emerge victorious.

“Genghis Khan” tells the story of Temujin (Conde, who also wrote and directed), a young Mongol prince who takes part in a series of challenges against rival tribes for land rights. Under the auspices of Burchou (Lou Salvador) and his beautiful daughter, Lei Hai (Elvira Reyes), Temujin uses his wits to prevail against larger, stronger opponents to emerge victorious. Unknown to any of the participants, Burchou’s advisor had arranged for his lord’s forces to massacre all the rival tribal leaders at that evening’s celebratory feast. Temujin barely escapes with his life, and makes his way home to find his village destroyed and his mother near death.

Instilled with a desire for revenge, the young prince begins spreading the word of Burchou’s treachery, forging alliances and building a power base that will culminate with him ascending to the position of Genghis Khan.

As far as classics go, reminders of the passage of time are unavoidable, be it in the wardrobe, acting style, soundtrack or hairstyles (Luke and Han’s 70’s haircuts in the first “Star Wars,” for instance). What makes a film endure, ultimately, is the ability of the narrative to resonate with audiences, regardless of budget, star power or box office. Thankfully, though it was with some trepidation that this reviewer approached “Genghis Khan,” it is with equal measures of relief and awe that I can report that the film holds up surprisingly well, its themes of honor, family, loyalty, and betrayal still ring true, over 60 years after the fact.

Making no pretense toward historical accuracy, Conde, along with frequent collaborator (and future National Artist for Visual Arts) Carlos Francisco, chose a straightforward tale of adventure, derring-do and loyalty in which to frame their subject of the Mongol who would be Khan. As written and performed, Conde’s Temujin is a character with a mind as deadly to his enemies as any blade, a far cry from the mighty barbarian warrior of legend (as seen in 2007’s “Mongol,” from Kazakhstan) and/or battle-weary chieftain (a legendarily miscast John Wayne in the 1956 Hollywood version) that would characterize later portrayals.

This emphasis on Temujin’s mental faculties is not to say that the film is lacking in the action department – quite the opposite, in fact. Small and large-scale fisticuffs abound; anachronistic European fencing techniques, missed cues and occasionally spotty choreography notwithstanding, Conde’s fight sequences are on par with any number of Hollywood productions of the period (which is more than can be said of many local films, then or now). Thankfully, the strength of the story and performances are able to smooth out any rough edges left by the occasional dodgy swordfight.

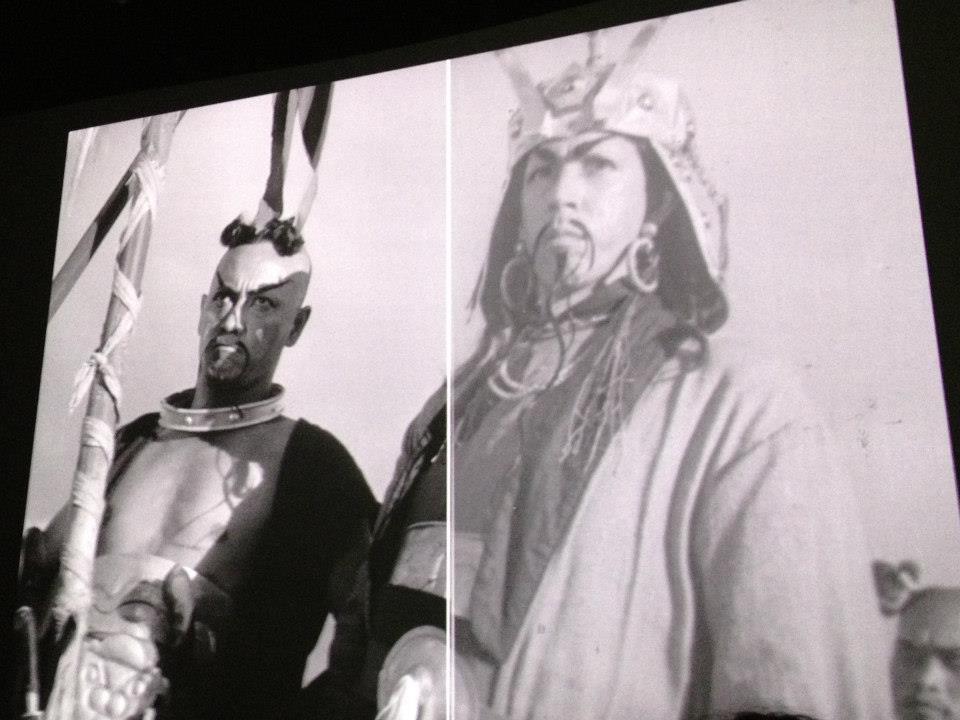

Prior to the screening, representatives from L’Immagine Ritrovata of Italy gave a short presentation on how, for the better part of a year, they scanned every frame of the film into a computer (at 2k resolution) and the painstaking process of digitally removing over 60 years of damage from moisture, scratches, fingerprints, warping, shrinkage, dirt and mold to bring “Khan” back to life.

Visually, especially for those who have only ever seen the film in bootleg form, the picture quality is a revelation, the fruits of L’Immagine Ritrovata’s labor on full display. Contrasts are good, with little bleeding and sparing use of digital noise reduction applied to the overall image. While not quite pristine – some reels were more damaged than others – it’s no exaggeration to say the film has never looked this good, with the characteristically crisp black and white cinematography coming across beautifully in glorious HD.

Such praise cannot be heaped on the aural front, however; while significant time and effort was also put into resurrecting the audio, the source material is rife with hisses and pops inherent to films of the period, especially one as neglected as “Khan.” Furthermore, the surviving prints L’Immagine Ritrovata worked on were of the international festival version, featuring English narration dubbed over the original dialogue. The Tagalog dialogue is still audible – for the most part – but one longs for a chance to see the film in its unedited form.

The restoration work undertaken by L_Immagine Ritrovata is nothing short of miraculous, as seen in this side-by-side comparison.

Despite being made on what international audiences would consider a shoestring budget (roughly P125,000, according to Conde), the filmmakers were able to make the most of the resources they had, whether it was using jeepney headlights to augment the lighting of night scenes or utilizing kalesa-pulling horses sourced from Binondo as Mongol steeds. Imaginative hairstyles and costume designs (also by Francisco) put those of current local productions to shame, as do the details in the various props and weapons.

In “Khan,” Conde and his cohorts were able to craft a true Filipino cinematic gem that still holds up today, not as an oddity or footnote, but as a shining example of what our filmmakers used to be capable of. The cinematography, pacing and editing on display give credence to what Conde’s son, Jun Urbano, said in his remarks prior to the premiere screening, “My father was ahead of his time.”

Indeed, so complete is the directorial conviction on display and so clear the ambition (and sheer audacity) that it is easy to forgive the plains and fields of Taytay standing in for the Gobi Desert in much the same way we forgive the pterodactyls in “Citizen Kane.”

“Genghis Khan” is considered a classic, and rightfully so. If it were only remembered as a product of its time, it would already be worthy of inclusion in the history books. As an artifact of an age when a Filipino production could stand proud and be recognized alongside the finest of world cinema, however, anyone who claims to be a proponent, student or practitioner of local film would do well to catch a screening and take notes. –KG/HS, GMA News

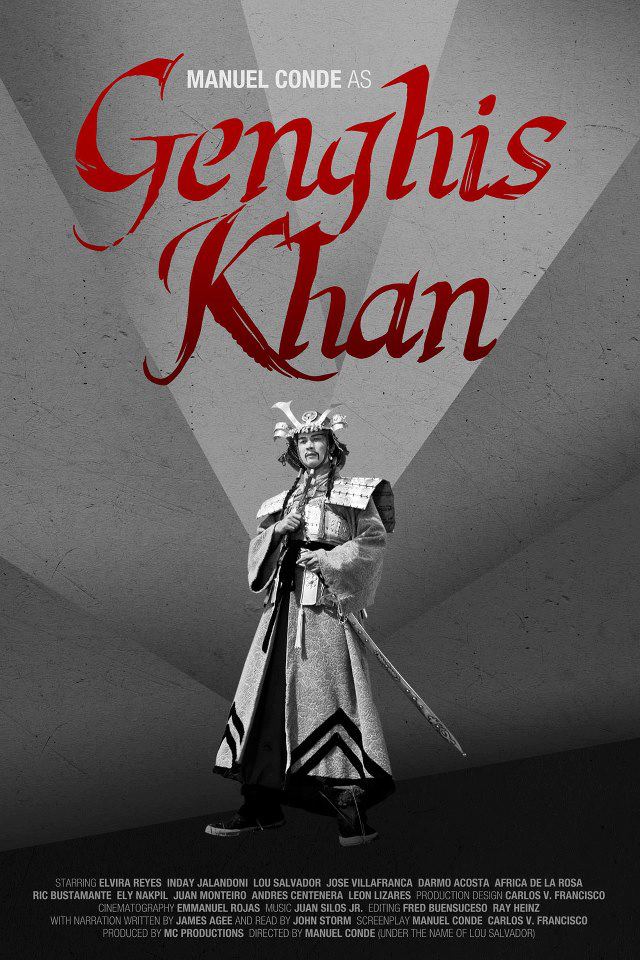

Re-release poster courtesy of Film Development Council of the Philippines

Vintage poster courtesy of Video48

Tags: genghiskhan, filmreview

More Videos

Most Popular