Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Theater review: The tale of a house foul with gore: 'Ang Oresteyas'

By VIDA CRUZ, GMA News

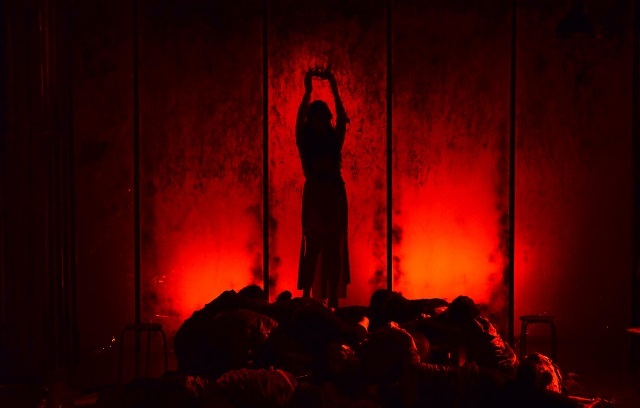

Aeschylus's trilogy is brought to life in "Ang Oresteyas". Photo by Chrissy Agay (Tanghalang Ateneo)

The young Orestes (Nicolo Magno) screams and staggers onto the dim stage, half-mad and drenched in blood, begging the audience to judge him.

Just then, Kasandra, the prophetess no one listens to (Opaline Santos), walks out amid the jerkily-dancing chorus and their metal stools and the three pillars comprised entirely of metal prison bars (designed by Charles Yee).

She proclaims to the audience that Orestes comes from a cursed and bloody line of kings and usurpers, and that he is guilty of murdering his mother Klytemnestra (Frances Makil-Ignacio), who murdered his father Agamemnon (Brian Sy), who murdered Orestes' eldest sister Iphigenia as a war offering to the gods.

The rest of the play painstakingly details the motives and the events that led up to each murder, making it ever more difficult for the viewer to judge Orestes as each side of the story is revealed.

In line with the thrust of Tanghalang Ateneo's 35th season—"Reimagining the Greeks"—the university's most senior theater company staged "Ang Oresteyas," as adapted by Jay Crisostomo IV from Aeschylus's trilogy of plays, "The Oresteia," and directed by Dr. Ricky Abad and Myra Beltran (who also did the choreography).

Milk and blood, black and white

"The Oresteia" is a traditional tale of murder, revenge, justice, and destiny. Performed 2500 years ago in Ancient Greece, this play preceded the more well-known "Oedipus the King" written by Sophocles, a student of Aeschylus. Aeschylus, in turn, is known as the "Father of Tragedy."

The genius of Jay Crisostomo IV was in the way the script was made for a contemporary Filipino audience. "Ang Oresteyas" spooled out into a tale still featuring murder, revenge, justice, and destiny—but it also had something to say about war, family dynasties, adultery, homosexuality, the voice of the masses, the voices of women, sexual politics, and whether the siren call of blood is truly thicker than water (or in this case, milk; there was much reference to mother's milk mixed with blood in this play).

If this does not resonate with the current situation of contemporary Filipinos, I don't know what does.

Sound and the Furies

What is fascinating about the use of the Greek chorus is its many functions—slaves, masses, inner conscience, the Furies (also known as the Erinyes, the Greek goddesses who relentlessly pursue men who have committed crimes). And they do all this while dancing, humming, arguing amongst themselves, making asides to the audience about their "beloved" rulers.

In fact, legend has it that, when the play was first staged in Ancient Greece and the Furies arose around Elektra by Agamemnon's grave, it struck such a fear into the audience that several pregnant women (or one woman, depending on the source) miscarried and died on the spot.

However, in that particular performance I got to watch, the chorus at times lost its synchonicity: some of the foot stomping and arm waves were off and occasionally the energy seemed to flag.

That particular scene with Elektra by the grave and black-veiled chorus doing a robotic dance lost somewhat its chilling-factor—but perhaps more of that can be attributed to the laughter of the audience. I did not realize 'til much later that they were very possibly laughing at the eerie song playing during the scene: a bunch of high-pitched voices humming over and over again what sounds like "Numnumnum."

In any case, this is not the fault of the chorus, and the music (done by Teresa Barrozo) was enticing enough for me to want a copy of any soundtracks the theater troupe may have produced.

Scene-stealers

Scene-stealers

The occasional drop of energy was balanced out by the lead actors, whose entrances, deliveries, and little nuances made this reviewer's hair stand on end.

Makil-Ignacio's Klytemnestra was particularly riveting whenever she went weak in the knees with the vengeance she harbored for her dead daughter; in her imitation of a queenly Filipino soap opera matron what with the way she shouted orders at the slaves; and when, with a tilt of her chin and raised eyebrows, she commanded her lover Agistos (Joseph dela Cruz) to fit her fiery high-heels to her feet like some kind of a dominatrix Cinderella. During Agamemnon's death scene, Klytemnestra was quite imposing, with her figure painted in shadow and a dim red light sharply-defining the darkened carnage (and it is these scenes that made me willing to overlook some minor slip-ups in the timing of the lighting, such as those few times it would come on even before Elektra's stage exit).

Miela Sayo's portrayal of Elektra, Orestes's remaining elder sister, and Santos's Kasandra, also deserve some note: both actresses did a good job of fleshing out the characters—wenches, little girls-turned-half-wild with the loss of their innocence and homes, and ultimately, opinionated women without voices.

The manner in which these three women often stole the scenes from the more-than-competent male leads was rivaled only by the nice touch of unresolved sexual tension moments between Orestes and his friend, the mute prince Pylades (Arvin Trinidad). The only other time I have ever heard such hooting and squealing from an audience over two men who are so clearly attracted to one another was during the televised concert featuring the actors of popular GMA soap opera, "My Husband's Lover."

Not surprisingly, Pylades, the more expressive and often-ignored of the pair, became a crowd favorite.

What's more, the audience got to see this tragic drama played out by actors dressed in steampunk-like military gear (Agamemnon), a sultry red dress befitting a modern socialite (Klytemnestra), and ruined finery in the form of torn stockings and frayed hems that bestow an almost rockstar-like aura for fallen royalty (Orestes, Elektra, and Kasandra). Pylades reminded one of Aladdin—bare-chested and donning white trousers and an embroidered white vest. Kudos to first-time costumer designer Chelsea Ong for the intricacy of the details.

Deleted gods

Part of what made this adapted-to-Filipino version so novel—apart from the dance segments—was the way it engaged its viewers.

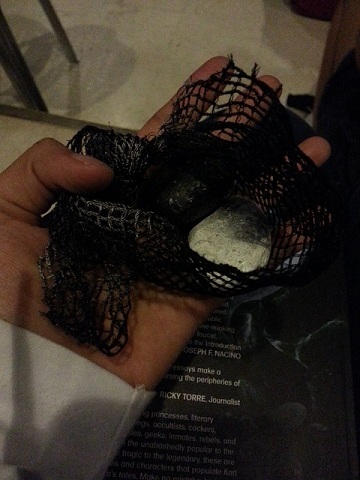

Select members of the audience were given a netted pouch containing two stones: black for "guilty" and white for "not guilty," and this reviewer was lucky to be among those who received stones. It made certain that the viewer considered all sides very carefully before casting their vote.

Did the audience's votes have any bearing on the end of the play? Yes—but not in the way you'd think.

This engagement of the viewers was not present in the original play, however. Instead of the audience passing judgment, the role was filled in by the Greek gods Athena and Apollo, especially in the last of the trilogy, "The Eumenides." The playwright deleted both gods and the happy ending from the original story and transferred the role of the former to the audience, thus summing up the entire third play and leaving it open-ended. Very fitting, as in this day and age, it has become increasingly difficult to judge anything by the black-and-white standards traditionally accorded to the gods and to religion.

This interpretation was visually reflected by the grayness of the stage, the dirty bars, and the warring aspects of the different personalities onstage: warmongering Agamemnon returned victorious from Troy but filled with remorse and humility for the sheer number lives lost and youth spent; Klytemnestra murdered her husband only because he betrayed her by sacrificing a daughter she loved so well; Orestes was by nature an honorable young man, but his manner of honoring his father was through the murder of his mother. The vicious cycle continues.

But religion and spirituality were not entirely gone from the play, whether erased by brutality or by the discerning aesthetics of the playwright.

My favorite scene was when Agamemnon and Klytemnestra met in what looked to be the afterlife, both wearing black and lit in a pale, watery light that both neutralized the entire scene and served to calm the audience after sitting through several emotionally-charged scenes. All the more was the theme of a gray morality highlighted in this restrained, moving scene between husband and wife—it shifts the burden of judgment from the gods to humans.

The verdict

The verdict

"Ang Oresteyas" is hard to like on the level of the pleasurable. But the play was not designed to make the viewer feel good; it was designed to make them think, to reflect on gray moralities. But on that note, since I spent the play's two hours switching between the black stone and the white stone, I congratulate directors Abad and Beltran and the entire cast and crew on a job well done.

And for that reason, apart from the the use of booze and smoke and graphic violence and sexually explicit scenes, this viewer strongly advises parents to leave their younger children with relatives or friends. They are not yet ready for this kind of play.

As to gray moralities and the use of the black and white stones when Orestes so clearly committed the murder, well, the play also asks its viewers to judge not just the act, but the intention behind it as examined via the characters.

For the record, I believed Orestes's intentions were pure, and very nearly laid down the white stone. However, only the audience was privy to the afterlife scene, which finally equalized Orestes's parents in both sin and mercy. And to quote Klytemnestra, the living, breathing Orestes's troubles were just beginning. The gods have been deleted, there is no room for deus ex machina in the living world, and the living do not know what transpires in death.

We all must be held accountable for our actions and take charge of our destinies, afterlife aside.

Black. — BM, GMA News

"Ang Oresteyas" ran from July 10-26 at Ateneo de Manila University's Rizal Mini-Theater. It is the first of Tanghalang Ateneo's plays for their 35th season.

Just then, Kasandra, the prophetess no one listens to (Opaline Santos), walks out amid the jerkily-dancing chorus and their metal stools and the three pillars comprised entirely of metal prison bars (designed by Charles Yee).

She proclaims to the audience that Orestes comes from a cursed and bloody line of kings and usurpers, and that he is guilty of murdering his mother Klytemnestra (Frances Makil-Ignacio), who murdered his father Agamemnon (Brian Sy), who murdered Orestes' eldest sister Iphigenia as a war offering to the gods.

The rest of the play painstakingly details the motives and the events that led up to each murder, making it ever more difficult for the viewer to judge Orestes as each side of the story is revealed.

In line with the thrust of Tanghalang Ateneo's 35th season—"Reimagining the Greeks"—the university's most senior theater company staged "Ang Oresteyas," as adapted by Jay Crisostomo IV from Aeschylus's trilogy of plays, "The Oresteia," and directed by Dr. Ricky Abad and Myra Beltran (who also did the choreography).

Milk and blood, black and white

"The Oresteia" is a traditional tale of murder, revenge, justice, and destiny. Performed 2500 years ago in Ancient Greece, this play preceded the more well-known "Oedipus the King" written by Sophocles, a student of Aeschylus. Aeschylus, in turn, is known as the "Father of Tragedy."

The genius of Jay Crisostomo IV was in the way the script was made for a contemporary Filipino audience. "Ang Oresteyas" spooled out into a tale still featuring murder, revenge, justice, and destiny—but it also had something to say about war, family dynasties, adultery, homosexuality, the voice of the masses, the voices of women, sexual politics, and whether the siren call of blood is truly thicker than water (or in this case, milk; there was much reference to mother's milk mixed with blood in this play).

If this does not resonate with the current situation of contemporary Filipinos, I don't know what does.

Sound and the Furies

What is fascinating about the use of the Greek chorus is its many functions—slaves, masses, inner conscience, the Furies (also known as the Erinyes, the Greek goddesses who relentlessly pursue men who have committed crimes). And they do all this while dancing, humming, arguing amongst themselves, making asides to the audience about their "beloved" rulers.

In fact, legend has it that, when the play was first staged in Ancient Greece and the Furies arose around Elektra by Agamemnon's grave, it struck such a fear into the audience that several pregnant women (or one woman, depending on the source) miscarried and died on the spot.

However, in that particular performance I got to watch, the chorus at times lost its synchonicity: some of the foot stomping and arm waves were off and occasionally the energy seemed to flag.

That particular scene with Elektra by the grave and black-veiled chorus doing a robotic dance lost somewhat its chilling-factor—but perhaps more of that can be attributed to the laughter of the audience. I did not realize 'til much later that they were very possibly laughing at the eerie song playing during the scene: a bunch of high-pitched voices humming over and over again what sounds like "Numnumnum."

In any case, this is not the fault of the chorus, and the music (done by Teresa Barrozo) was enticing enough for me to want a copy of any soundtracks the theater troupe may have produced.

Family matters—like adultery, murder and revenge—unspool in "Ang Oresteyas." Photo by Rynel Mejia (Tanghalang Ateneo)

The occasional drop of energy was balanced out by the lead actors, whose entrances, deliveries, and little nuances made this reviewer's hair stand on end.

Makil-Ignacio's Klytemnestra was particularly riveting whenever she went weak in the knees with the vengeance she harbored for her dead daughter; in her imitation of a queenly Filipino soap opera matron what with the way she shouted orders at the slaves; and when, with a tilt of her chin and raised eyebrows, she commanded her lover Agistos (Joseph dela Cruz) to fit her fiery high-heels to her feet like some kind of a dominatrix Cinderella. During Agamemnon's death scene, Klytemnestra was quite imposing, with her figure painted in shadow and a dim red light sharply-defining the darkened carnage (and it is these scenes that made me willing to overlook some minor slip-ups in the timing of the lighting, such as those few times it would come on even before Elektra's stage exit).

Miela Sayo's portrayal of Elektra, Orestes's remaining elder sister, and Santos's Kasandra, also deserve some note: both actresses did a good job of fleshing out the characters—wenches, little girls-turned-half-wild with the loss of their innocence and homes, and ultimately, opinionated women without voices.

The manner in which these three women often stole the scenes from the more-than-competent male leads was rivaled only by the nice touch of unresolved sexual tension moments between Orestes and his friend, the mute prince Pylades (Arvin Trinidad). The only other time I have ever heard such hooting and squealing from an audience over two men who are so clearly attracted to one another was during the televised concert featuring the actors of popular GMA soap opera, "My Husband's Lover."

Not surprisingly, Pylades, the more expressive and often-ignored of the pair, became a crowd favorite.

What's more, the audience got to see this tragic drama played out by actors dressed in steampunk-like military gear (Agamemnon), a sultry red dress befitting a modern socialite (Klytemnestra), and ruined finery in the form of torn stockings and frayed hems that bestow an almost rockstar-like aura for fallen royalty (Orestes, Elektra, and Kasandra). Pylades reminded one of Aladdin—bare-chested and donning white trousers and an embroidered white vest. Kudos to first-time costumer designer Chelsea Ong for the intricacy of the details.

Deleted gods

Part of what made this adapted-to-Filipino version so novel—apart from the dance segments—was the way it engaged its viewers.

Select members of the audience were given a netted pouch containing two stones: black for "guilty" and white for "not guilty," and this reviewer was lucky to be among those who received stones. It made certain that the viewer considered all sides very carefully before casting their vote.

Did the audience's votes have any bearing on the end of the play? Yes—but not in the way you'd think.

This engagement of the viewers was not present in the original play, however. Instead of the audience passing judgment, the role was filled in by the Greek gods Athena and Apollo, especially in the last of the trilogy, "The Eumenides." The playwright deleted both gods and the happy ending from the original story and transferred the role of the former to the audience, thus summing up the entire third play and leaving it open-ended. Very fitting, as in this day and age, it has become increasingly difficult to judge anything by the black-and-white standards traditionally accorded to the gods and to religion.

This interpretation was visually reflected by the grayness of the stage, the dirty bars, and the warring aspects of the different personalities onstage: warmongering Agamemnon returned victorious from Troy but filled with remorse and humility for the sheer number lives lost and youth spent; Klytemnestra murdered her husband only because he betrayed her by sacrificing a daughter she loved so well; Orestes was by nature an honorable young man, but his manner of honoring his father was through the murder of his mother. The vicious cycle continues.

But religion and spirituality were not entirely gone from the play, whether erased by brutality or by the discerning aesthetics of the playwright.

My favorite scene was when Agamemnon and Klytemnestra met in what looked to be the afterlife, both wearing black and lit in a pale, watery light that both neutralized the entire scene and served to calm the audience after sitting through several emotionally-charged scenes. All the more was the theme of a gray morality highlighted in this restrained, moving scene between husband and wife—it shifts the burden of judgment from the gods to humans.

The audience as jury delivered their own verdict. Photo by Vida Cruz

"Ang Oresteyas" is hard to like on the level of the pleasurable. But the play was not designed to make the viewer feel good; it was designed to make them think, to reflect on gray moralities. But on that note, since I spent the play's two hours switching between the black stone and the white stone, I congratulate directors Abad and Beltran and the entire cast and crew on a job well done.

And for that reason, apart from the the use of booze and smoke and graphic violence and sexually explicit scenes, this viewer strongly advises parents to leave their younger children with relatives or friends. They are not yet ready for this kind of play.

As to gray moralities and the use of the black and white stones when Orestes so clearly committed the murder, well, the play also asks its viewers to judge not just the act, but the intention behind it as examined via the characters.

For the record, I believed Orestes's intentions were pure, and very nearly laid down the white stone. However, only the audience was privy to the afterlife scene, which finally equalized Orestes's parents in both sin and mercy. And to quote Klytemnestra, the living, breathing Orestes's troubles were just beginning. The gods have been deleted, there is no room for deus ex machina in the living world, and the living do not know what transpires in death.

We all must be held accountable for our actions and take charge of our destinies, afterlife aside.

Black. — BM, GMA News

"Ang Oresteyas" ran from July 10-26 at Ateneo de Manila University's Rizal Mini-Theater. It is the first of Tanghalang Ateneo's plays for their 35th season.

More Videos

Most Popular