Art review: Mostly male melancholia at the Ateneo Art Awards

It’s been years since I cared tremendously about the Ateneo Art Awards. That is borne mainly of a self-aware arrogance, where I tend to wait for the winners’ homecoming exhibits – that is, if they get an artist grant that (ideally) comes with being one of the winners.

This year, my interest was really limited to Buen Calubayan’s “Fressie Capulong.” Calubayan’s work is one I’ve followed since 2009, when I interviewed him for being awarded one of 13 young and exciting artists by Nokia and the Philippine Daily Inquirer. Then, Calubayan seemed to be at the tail-end of a series of paintings that reconfigured and reassessed, and therefore blasphemed against, images of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, and Pinoy Catholicism in general.

After a stretch of no exhibits and no art, and becoming an employee of the National Museum, Calubayan’s December 2012 (sort of) comeback exhibit was barely noticed. It also barely sold anything.

Winning the Ateneo Art Award for 2013 could only feel like retribution for “Fressie Capulong” and Calubayan. Though that might be said for most of the artists in this shortlist, too.

It had become expected, the shortlist that the AAA would come out with every year, and this is not entirely the organizers’ fault. After all, the process is one that sends out a call for nominations of exhibits, which is then shortlisted by a jury.

Since the 2009 AAA, the shortlist has had the usual suspects, certain artists have become "suki," and the exhibit looks the same year-in year-out. That might be the nature of a competition such as this, where a jury (of the usual suspects too) would come up with the same(-looking) shortlist every year.

On this, the AAA’s 10th year though, there was reason to celebrate. The exhibit looks calmer than usual, if not austere. Unlike years when it seemed like a contest on concept or grand installations, this year it is mostly paintings and framed works. Unlike years when there seems to be the need for some shock value or the obvious art-in-your-face, this year there is a quiet to the shortlisted exhibits.

At least it was this calm and quiet that overpowered Leeroy New’s loudly colored monsters; it also became easy to miss Nikki Luna’s glass-encased soil installation.

Because one cannot but get carried away by the wonder of works that are limited to a frame, and tacked to a wall. There was something comforting about walls filled with works familiar because personal, because universal, because the reaction to these is visceral. At the same time there was the element of surprise in the diverse temperament in the works here, in the distinct voices of most of these artists.

Meditations on space

Say, Pio Abad’s “Zabludowicz Collection Invites Pio Abad,” which is both an uncanny display of nostalgia for nation and a real concrete act of collecting and sifting through information about a self that does not exist anymore given migration. It is uncanny because the installations look familiar but are not quite what you know: a set of framed stamps with unfamiliar print, a bright pink scarf hanging on a wall with an image of a building not here.

It might be said that it is personal experience that impinges upon the possibility that the spectator might connect with the art that is here.

Which is true too for the work of Ryan Villamael, particularly for the exhibit “Kosmik” where his creative process is one of meditation. Engaging with various religions and meditating on these encounters, Villamael produced “Solaris,” a series of cut paper art that look like reconfigured images of gods and goddesses.

His other shortlisted exhibit, “Flatland,” is a meditation on space, a reimagination of landscapes and structures that constitute our cities. Whether within geometric frames that come together like puzzle pieces to form a bigger shape, or large frameless paper cuts installed against a wall, “Flatland” works with our sense of landscapes and treats it as one-dimensional. Already lost, here found to some extent.

Zean Cabangis’s “Goat Paths” delves into the contemporary predisposition to consume. Here, the objects of collection and acquisition are layered with new shapes and unfamiliar strokes, creating a new image that is both familiar and strange. As the objects become secondary to the layers of shapes and strokes, what Cabangis creates is erasure at its best, where it is not total obliteration of image that is the point of critique as it is the rendering of an object’s habitation of space, its reconfiguration. The final image seems like a meditation not so much on consumption as it is on space, and the lack of it.

Allan Balisi’s “Hollow Spaces” meanwhile plays with the idea of space by messing with our sense of size and scale. Large hands hold a seemingly empty house, people look in on a house that is the size of a dollhouse. Using oil and graphite, the images are monochromatic, and eerily so – as if these are of a different time, seemingly of the past, but also absolutely of the future. The effect is disconcerting, where the world we are treated to is both believably real but also hauntingly fictional. Or is it?

Joey Cobcobo’s “Lola: 101” are a series of monoprint portraits on shifu paper that pay tribute to the symbol of the grandmother as the every woman that we encounter in our lives, not so much a biological connection as it is about respect for elders. That these are not necessarily faces, as they are leaves and twigs, objects found in nature, is part of this artmaking’s delicateness. As it is about a devotion, one that adds a layer to the personal that is already here.

Melancholia and the personal

But probably the personal is what might define much of the works here, as it is what took home the year’s major prizes.

Calubayan’s “Fressie Capulong” was about the archiving of personal history, about the frame that the mother sets upon the child. Made up of some of Calubayan’s early works reconfigured, some images spoke of childhood and becoming. These were tied together by the set of images of Fressie Capulong, in different contexts, wearing different things, colored differently in each frame. The effect is of entering someone else’s home recreated in these images, the people that inform his being tied to but one name.

Charles Buenconsejo’s might have been the dark horse of the three chosen winners for this year’s AAA, not overtly personal as it is. And yet while “Reality is a Hologram” seems less personal than any of the other works here, there was a sense of emotion – of melancholia – still. It might be the dark colors of these lambda metallic prints; it might also be the soft lines and light movement that these images seemed to invoke. That these are also interventions in photography – which is also part of Buenconsejo’s body of work – is what makes this meditation as personal as any other.

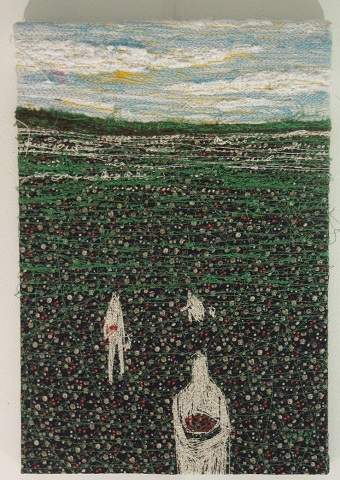

Working with thread on textile, Napay creates images of living that we would know to be real, and yet given his creative vision actually look like works of framed whimsy. It has to be the medium, yes, but also it is the decision to portray real moments and spaces, and remove them from the “real” image.

That is, the factory is not a structure as it is people at work; the harvest is an endless sea of green and later on bright blue sky; a couple sleeping happens under the star-riddled night sky.

The effect is twofold: from afar, it looks like abstract art, the images of people are but sketches made of thread.

Up close, and after staring at it far longer than I would usually allow myself, what shines through is the skillful portrayal of moments, and the kind of emotion that the use of thread invokes.

That is, the knowledge that Napay’s mother is a seamstress for one; but more important the sense that thread on textile is a more personal engagement with material, is an act of weaving and creativity that is about absolute control, and to some extent total whimsy.

The effect of Napay’s work is abstraction. But the process itself is revealed as, the final product is, a meditation too on melancholia.

Milestones, and changes are afoot

On September 8, the Ateneo Art Awards is opening its 10th year anniversary exhibit, including the exhibits and artists that won this year. They are also announcing changes to the AAA.

Though details have yet to be revealed, I cannot but feel a bit sad, if not be a little wary, of these changes. This year’s shortlist have proven after all how the AAA has become a more inclusive display of the kind of artmaking that’s going on, the kind of creativities that are here. To change it now might mean going back to an exclusivity, if you will, that surrounds any award-giving process to begin with, but even more an award that comes from the Ateneo.

Ah, but the Ateneo Art Awards has got my heart back – it must be the male melancholia in this year’s exhibit. Here’s hoping they prove that change will do us all some good. — BM, GMA News

“Marking Time” has been moved from Shangrila Mall EDSA to the Ateneo Art Gallery. “Ateneo Art Awards 2004–2013: A Retrospective,” opens on September 8, 4:00PM. Leong Hall Auditorium, Ateneo de Manila University. Vernissage follows at the Ateneo Art Gallery.