Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

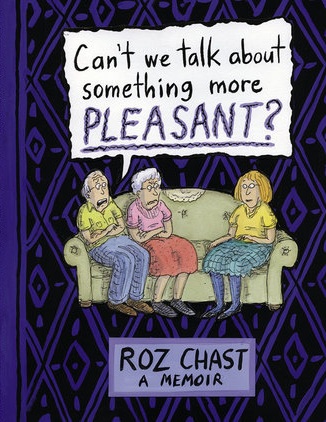

New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast takes on eldercare in new book

By RANDI BELISOMO, Reuters

NEW YORK - Cartoonist Roz Chast, famous for her deceptively simple drawings in The New Yorker magazine, is now touching a chord with the “sandwich generation” with her wryly sensitive graphic memoir about caring for her aging parents.

Book cover from RozChast.com

Blunt but witty, her words and images have sparked thousands of letters from caregivers nationwide. “They all say nobody talks about it,” Chast told Reuters Health.

Topping The New York Times graphic books best seller list for nine weeks, her story may help lift the silence among those with aging and ill parents.

“I get nervous checking my webmail, because I can’t respond to all these people,” Chast said. “Whether they are Midwestern Lutherans or Jewish girls from Brooklyn, details are different, but the story is the same.”

Chast didn’t know how to broach the painful issues of eldercare with George and Elizabeth, who lived independently into their 90s. “I didn’t want to bring up these issues, but there comes a time you have to,” she said.

The drawings show how Chast hired an elder lawyer, someone better able to tactfully address medical options. Elizabeth, a self-described “Jewish Christian Scientist,” informs the attorney that hospitals are where “you go to die” and that doctors “have a God complex.” Her preferences, however, are clear, and emphasized in capital letters. Elizabeth does not wish to become “A PULSATING PIECE OF PROTOPLASM!”

Hospitals cannot be avoided. George breaks a hip, and Elizabeth’s diverticulitis worsens. George’s fracture leads to a rapid decline. “He wanted to pack it in,” Chast said. “My mother was furious, because she wanted him to fight.” His physician recommends hospice.

“Hospice is a very strange thing,” Chast said. “You can sugarcoat it anyway you want, but basically it means we are not going to do more because there is nothing more to be done.” Elizabeth remains in denial, insisting soup will do the trick.

Elizabeth survives George by two years, a financial drain Chast describes candidly. “If she lived another year, I would have had to take a second mortgage or go into our savings for our kids’ college,” Chast said. “I was really starting to fray.”

The $7,000 monthly facility fee prompts a bedside conversation, recommended by a hospice aide, in which she tells Elizabeth “you are running out of money.” Elizabeth dies days later.

“It was shocking that I said that, but the hospice people knew I was starting to freak out,” Chast said.

Its wit, realism and willingness to shatter taboos make this memoir a must-read for those facing similar circumstances, many health providers say. It is one of several graphic books released in recent years addressing serious illness and death in what is called a “golden age of comics” in healthcare by Penn State University humanities and medicine professor Michael Green.

“It does a fantastic job exploring ambivalences, challenges and mixed feelings one has around these issues,” Green told Reuters Health. Graphic stories such as Sarah Leavitt’s “Tangles” and Brian Fies’ “Mom’s Cancer,” he said, provide nuanced perspectives on the multi-dimensional topic of end of life care.

“Because they not only use words but images too, the images do a great job showing what it feels like,” Green said. “Emotional context gets conveyed that is moving to people.”

Such graphic memoirs normalize topics that aren’t discussed in American discourse, said M.K. Czerwiec, artist-in-residence at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “When you’re going through something like that, it’s great to know you’re not alone and to be able to laugh at it,” said Czerwiec, whose website is called “Comic Nurse.”

Chast is delighted to share those laughs with readers, stressing her tale is one of more light-hearted empathy than instruction.

Of caring for her parents, she said, “I don’t feel like I did a great job. It was trying to pick the least bad of a lot of bad options.” — Reuters

More Videos

Most Popular