Inside Culion, the Philippines' "Island of No Return"

CULION, Palawan - A tall gate stands firm a few steps away from the port of Culion Island in Palawan, welcoming visitors to Barangay Libis.

Hermie “Pastor” Villanueva, a 47-year-old tour guide, stood under the gate. “Leproso,” he said, gesturing to one side of the gate. “Sano,” he added, indicating the other side.

More than a century ago, the gate served as a boundary between two worlds -- that of the “leproso” (leper) and that of the “sano” (clean). It warned that you’re about to enter a leper zone.

Located at the northern tip of Palawan, the island of Culion used to be a leprosarium under the American commonwealth of the Philippines.

The municipality, by virtue of an Executive Order, was created for the sole purpose of segregating those afflicted with leprosy, which was then incurable.

Thousands were rounded up and exiled to the secluded island from different regions of the Philippines, the first few hundreds arriving in 1906. The colony ballooned to just short of 7,000 in 1933.

It was only in 2006 that the island was declared leprosy-free by the World Health Organization.

“1906 to 2006. 100 years before the leprosarium was formally closed by the World Health Organization,” Pastor mulled.

Island of No Return

“During that time...there’s no way to escape kapag nilagay ka dito,” Pastor told GMA News Online in an interview.

Each year, hundreds died, but hundreds more were admitted. More than a thousand were recorded to have escaped in the span of a century. But, in the absence of a cure, they mostly died.

After all, Culion wasn’t called the “Island of No Return” for nothing.

“They were separated from their families. Then they take them here, very little possibility na ikaw ay makikita ng family mo,” Pastor said.

His own grandmother, Rosalia, was afflicted with leprosy. While they detected the disease as early as when she was a teenager, it only manifested after she gave birth to her firstborn, Pastor’s father.

Rosalia’s husband left her and her son was sent to live elsewhere. She was sent to Tala Leprosarium in Caloocan City first, before being transferred to Culion.

It was the end of life as she knew it, but Rosalia started anew. She fell in love with a coworker in Culion, a victim of leprosy who died many years before her.

And years after a cure was introduced, she was reunited with her grandson when Pastor moved from Manila to Culion in 1987.

Perlas ng Palawan

Even now, Culion is haunting.

The second floor window of Maya Hotel, previously a ladies’ dormitory called Hijas de Maria, overlooks the endless ocean below. Strong winds crash against the window screen producing low moaning sounds, an occasional whistling noise.

The area was the site of the bloody 1932 revolution that would eventually push authorities to repeal its restrictive regulations on marriage between persons afflicted with leprosy.

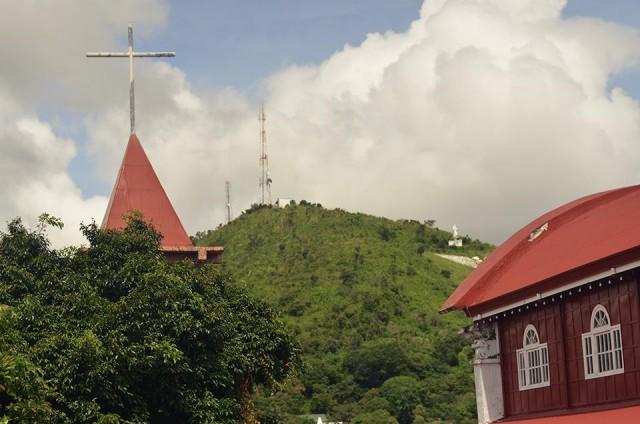

The island has so many stories to tell: There is the lighthouse that used to function as a patrol station, the General Hospital that once held nearly 3,000 patients, the nun-controlled dormitories that have been remodeled into hotels.

The government employees or nurses that used to be written off as good as dead.

There were supposedly around 300 survivors, or registered patients that are still in Culion, but Pastor said he only sees around 30 of them up and around. They sweep the floors, help maintain the island's heritage sites, take duties in the hospitals, hold government positions.

What used to be the Island of the Living Dead now considers itself the “Perlas of Palawan.” Pastor said Culion is the last frontier of Palawan, having been largely untouched compared to the tourist destination sites of the province.

He boasted of the island’s waterfalls, viewing decks, and snorkeling sites.

However, he admitted that it was difficult promoting tourism in an island surrounded by so much stigma.

“Nakakaramdam ng discrimination, especially pag nasa Manila kami o nag-aaral. Yung previous generation, they don’t like to say na galing sila sa Culion. Ngayon hindi na masyado,” Pastor said.

He himself used to say he was from Coron, the shinier, more popular island, nearly a 2-hour boat ride away.

But Pastor, who remembers growing up in Culion and serving warm meals to the victims, said he learned to love his heritage.

“I’m part of the history. It’s my people. It’s my duty na sabihin ang kanilang history,” he said. — LA, GMA News

This story was produced through a trip sponsored by the 28th Philippine Travel Mart, presented by Philippine Tour Operators Association (PHILTOA).