Filtered By: Topstories

News

For PNoy, 66 bills not good enough to become laws

By ANDREO CALONZO, GMA News

A proposed law is like a track athlete. It has to have a name and a number for it to start moving. It needs to have enough supporters to be able to conquer various obstacles, including committee hearings, heated debates and several rounds of voting. It has to race against time to reach the finish line and become a law.

Some bills, however, never get to reach the finish line even after running through the legislative mill for years. During the 15th Congress, 66 bills failed to hurdle one final obstacle required for them to become laws: President Benigno Aquino III's approval.

But an opposition leader noted that had the President convened the LEDAC (Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council) more often, the vetoing of bills could have been minimized.

Veto power

But an opposition leader noted that had the President convened the LEDAC (Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council) more often, the vetoing of bills could have been minimized.

Veto power

The 1987 Constitution gives the President the power to veto bills which he thinks are not good enough to become laws. Section 27, Article VI of the Philippine Charter authorizes the President to return entire measures to Congress for reconsideration.

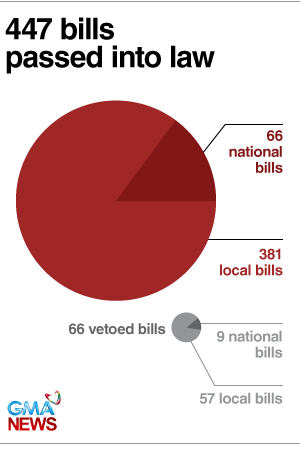

Based on records from the House of Representatives, the proposed laws that did not pass Aquino's scrutiny include 57 local bills and nine national measures that could have benefited certain sectors of the society.

The recently vetoed Centenarians Act, for instance, could have provided additional benefits to 7,000 Filipinos aged 100 years old and above. Aquino did not sign the bill because it could possibly hurt businesses in the country.

Even the simple bill declaring waling-waling as the Philippines' national flower did not get the President's signature. The government gazette did not publish an explanation for this veto.

Other national measures vetoed by the President include the bill protecting internally displaced persons, the bill giving fixed three-year terms to Armed Forces chiefs, the proposed Magna Carta of the Poor, the bill establishing the Career Executive System, the bill removing the height requirement for security officers, the Early Years bill and the bill granting Filipino citizenship to Indian philanthropist Gulshan Bedi.

Secretary Manuel Mamba, who heads the Presidential Legislative Liaison Office (PLLO), admitted that the President tends to be "very meticulous" when it comes to studying bills that are on the brink of enactment.

"He [Aquino] has been telling us that he doesn't want a bill to be lapsing into a law. He has to study it. He has to get inputs of agencies. Pinag-aaralan niya nang mabuti," Mamba said in a phone interview.

He attributed Aquino's tendency to closely scrutinize proposed legislations to the President's background as a lawmaker. Aquino spent 12 years in Congress before assuming the country's top executive post.

Mamba likewise defended the President's decision to veto certain bills, saying it is actually "good" for the country.

"This makes sure that we have quality laws. Every bill filed must be enforceable and implementable. Gusto niya na ang isang batas, mapapatupad talaga," the PLLO chief said.

He added that the number of laws vetoed by the President are "very little" when placed side by side the number of legislations passed during Aquino's almost three-year old presidency.

According to Mamba, 447 bills were passed into law during Aquino's first three years in office. Sixty-six of these measures were of national importance, while 381 were local bills.

'Counterproductive'

But House Minority Leader Danilo Suarez said that vetoing bills may not be productive at all, given the amount of time and resources used by lawmakers for a piece of legislation.

"To legislate is not an easy task. It involves a lot of expenditures and resources. Millions of pesos of the government's money are used just to pass a single bill," Suarez said in a separate phone interview.

The opposition leader added that some of Aquino's vetoes may even hurt his government's programs. Suarez particularly described as "counterproductive" the vetoing of the measure that could have given a fixed three-year term to chiefs of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

Aquino vetoed this bill in January last year for supposedly violating a provision in the 1987 Constitution banning the extension of service of military officers.

"That would definitely affect the modernization of our military and the efficiency of our Armed Forces," Suarez said.

"That would definitely affect the modernization of our military and the efficiency of our Armed Forces," Suarez said.

Solutions

Further, the House minority leader said that the vetoing of bills could have been minimized if Aquino convened the LEDAC more often.

"Iyan ay matagal na naming sinasabi. Kung nako-convene ang LEDAC, hindi mangyayari itong mga veto. Kung nagpapatawag ng LEDAC meeting, we will be able to see the body language of the President. Kapag sinabi niya na iveveto niya ang isang bill, magagawan ng paraan," Suarez said.

The LEDAC was created through Republic Act 7640, signed in 1992 by then-President Fidel Ramos. The council is supposed to be a "consultative and advisory body" chaired by the President, which can provide "policy advice... on vital issues affecting the socioeconomic development of the country."

Under Section 5 of this law, the LEDAC shall meet at least once every quarter. Aquino has only called two LEDAC meetings during his almost three years as president.

Mamba, for his part, admitted that every bill vetoed by President Aquino serves as a "lesson learned" for him and his office. He also encouraged government departments to actively monitor the development of bills that concerns them.

"Sobrang daming batas na pina-process sa Kongreso on a daily basis. We can only monitor some of those. We need all the help that we can get from the departments," the PLLO chief said. — RSJ, GMA News

Tags: noynoyaquino, vetoedbills

More Videos

Most Popular