11 ancient Chinese New Year traditions that are not observed anymore

Around GMA

Around GMA

LIST: Winners of the MMFF 2025 Gabi ng Parangal Purple Hearts Foundation brings joy via year-end gift-giving outreach Davao police say boy’s injury not caused by firecrackersArticle Inside Page

Showbiz News

Find out why the Chinese used to avoid dogs during Lunar New Year.

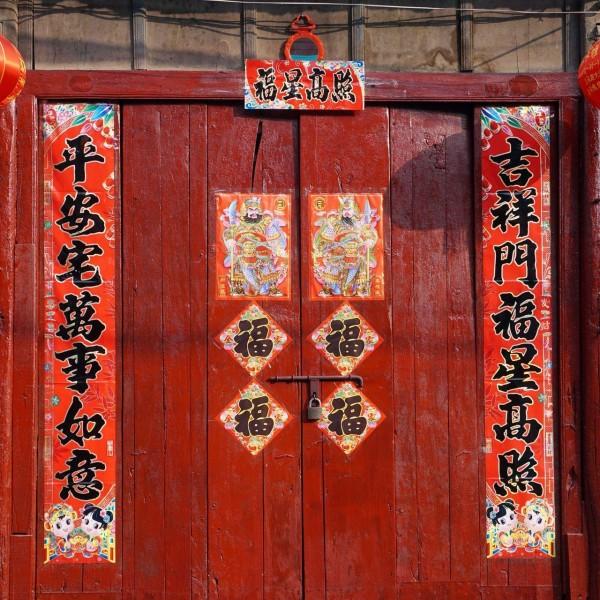

Chinese culture is filled with holidays and celebrations, and China's most important festival, the Spring Festival, better known as Lunar New Year and Chinese New Year, has produced numerous folk customs.

Chinese New Year traditions and superstitions you need to know

Dating back centuries, many traditions are deeply rooted in lore and superstition. But with China's fast-paced development, some old ways are being neglected.

Here are the 11 ancient Chinese New Year traditions and superstitions that are not observed anymore:

1. Offering sacrifices to the God of the Kitchen Stove

In the old days, the Chinese put a pair of couplets on the kitchen entrance, in hope that the God of the Kitchen Stove would put in a good year for them. The ritual is held on the 23rd (in North China) or the 24th (in South China) of the 12th month of the Chinese lunar year.

2. Greeting the God of the Kitchen Stove

After sending the God of the Kitchen Stove to Heaven, they welcome him back by setting off firecrackers, offering sacrificial objects, and burning incense and paper representing money.

3. Getting married without choosing a specific date

It was believed that nothing is a taboo for gods and humans, and there's no need to choose a specific date for getting married between the 23rd and 30th of the 12th month of the Chinese Lunar year.

4. Washing laundry or hair

The Chinese avoid washing their clothes or hair on the first two days of the Spring Festival, which is considered as the birthday of the Water God.

5. Steaming buns

Preparing dishes for the Spring Festival on the 29th of the 12th month of the Chinese lunar year was considered unlucky. Therefore, the people had to prepare steamed buns beforehand that will be served for the whole week of the Chinese New Year.

6. Sweeping the floor

Traditionally, sweeping the floor, taking out the trash, and splashing water outside during this period all signify tossing out incoming good luck and wealth.

7. Setting off firecrackers

Before, each Chinese household strived to be the first to set off "opening-door firecrackers" at midnight on the first day of the Chinese New Year. It symbolizes ringing out the old year and ringing in the new year. This traditional activity is slowly disappearing.

8. Avoiding dogs

According to the folklore, the God of Anger, also known as the Scarlet Dog, would roam on the third day of the Chinese New Year, presumably barking mad. They say, whoever ran into him would have bad luck, so many Chinese chose to stay at home all day.

9. Offering sacrifices to the God of Fortune

The Chinese used to offer a sacrifice to the God of Fortune on the 2nd day (in North China) or the 5th day (in South China) of the Chinese New Year. The rituals are held in stores or at home, with a whole goat, chicken, pig, or live carp as sacrifices.

10. Using sharp utensils and objects

Items like scissors, needles, and knives were deemed to be threatening and depressing as they could lead to disputes with others during the Chinese New Year period.

11. Sending off the God of the Poor

According to legend, the God of the Poor was very short and thin, and was fond of dressing in rags and eating porridge. As a result, folks would send him off to heaven rather than see him in rags on earth during the Spring Festival.

Are you still observing any of these Chinese New Year traditions?