Filtered By: Money

Money

ANALYSIS: Letting investment grade work for every Juan

By RONALD U. MENDOZA and KATHERINE PERALTA, Asian Institute of Management Policy Center

Do you have a bank account? If any of your family member gets sick, do you have health insurance as a fall back position? Have you ever taken out a housing, education or business loan? Do you own stocks?

If you answer "Yes" to any of the above, you are probably among the lucky one-third of the Philippine population with some level of access to financial markets.

If you answer "Yes" to any of the above, you are probably among the lucky one-third of the Philippine population with some level of access to financial markets.

People wonder how exactly 11 consecutive Philippine credit upgrades by debt-watchers Fitch, S&P and Moody’s between 2011 and 2014 will benefit the majority of Filipino families. Most of those who answered "Yes" to the questions above are likely to benefit directly from an easier credit environment.

Yet, for the majority of Filipinos who have little or no access to banks, credit and even basic financial products like insurance, the credit upgrades mean very little.

Deeper structural reforms are needed to make the financial and credit markets more inclusive for the vast majority of Filipinos. Unless we dramatically improve financial inclusion, inclusive growth and development will likely prove elusive.

Yet, for the majority of Filipinos who have little or no access to banks, credit and even basic financial products like insurance, the credit upgrades mean very little.

Deeper structural reforms are needed to make the financial and credit markets more inclusive for the vast majority of Filipinos. Unless we dramatically improve financial inclusion, inclusive growth and development will likely prove elusive.

Big firms are big winners

Thanks in no small part to sustained macroeconomic stability, declining public sector debt, and some progress in anti-corruption reforms, the Philippines received its first ever investment grade status in March 2013, allowing a portion of our firms and citizens to enjoy its benefits.

From 10 percent in 2004, the average bank lending rate has fallen to just about 5.5 percent. This is good news, notably for larger firms with an established access to financial markets.

For instance, San Miguel Corporation has increased its liabilities from P171 billion in 2008 to P804 billion in 2013. Ayala Corporation’s liabilities increased from PhP 92 billion to PhP 364 billion. Further, SM Investment Corporation (SMIC) increased its liabilities from P143 billion to P333 billion (See Figure 1.)

(FIGURE 1) Source: 2008 and 2014 Annual Reports of San Miguel Corporation, Ayala Corporation,

SM Investment Corporation, Aboitiz Group, and DMCI.

In 2014, the LT Group borrowed $850 million (P37 billion) from a bank syndicate to finance the buyback of Philippine Airlines. Andrew Tan’s Emperador International Ltd. borrowed P15 billion from HSBC and JP Morgan Chase to finance its overseas expansion. Ayala Corporation unveiled plans to borrow $1.6 billion (P70 billion) to fund two major power plants in Luzon and Mindanao.

Many of the investments could generate jobs and grow employment, or enhance economic competitiveness to entice investments. These are positive signs, yet it would be critical to examine whether, and to what extent, the majority of companies – not just the large ones or congolmerates – are benefiting from easier credit.

Decline in SME loans

The economics of lending tend to favor larger firms. Lending to smaller companies typically implies higher costs in relation to lower loan amounts. Hence, the Magna Carta for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises try to achieve a more level playing field by requiring banks to set aside at least 10 percent of their loan portfolio for MSMEs, with 8 percent going to micro and small enterprises, and 2 percent to medium enterprises.

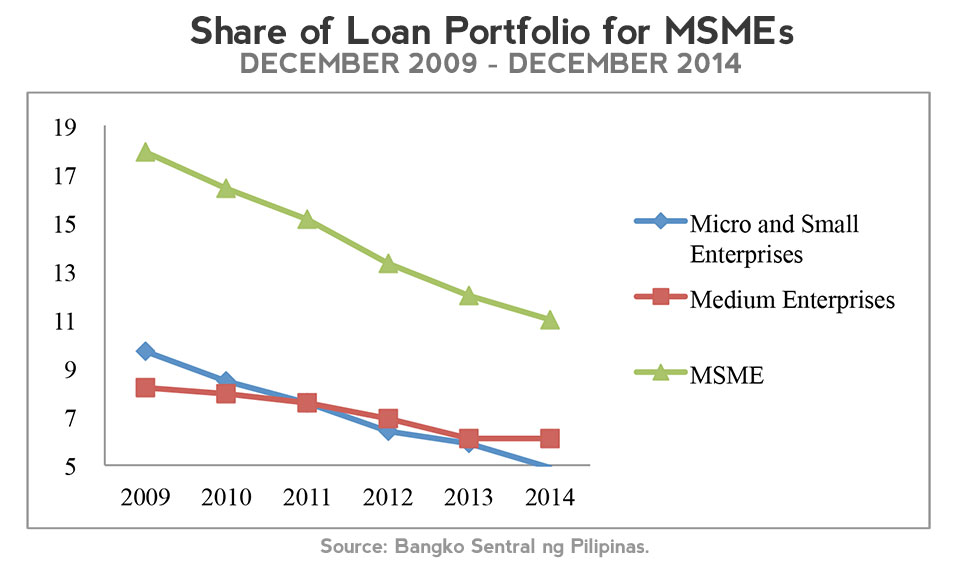

Although lending to MSMEs has grown by about 40 percent since 2009, the figure is actually smaller compared to the bangking industry's total loan portfolio at P4 trillion as of December 2014. In fact, the percentage of compliance to lending under the MSME provisions has dropped from 17.9 percent in December 2012 to around 11 percent in December 2014 (or just a percentage point above the minimum required by the Magna Carta).

Loan allocations to micro and small enterprises started to fall below the 8 percent minimum in 2011 – when it registered at 7.56 percent. For every percentage point of non-compliance, banks face a fine of P400,000 for micro and small enterprises, and P100,000 for medium enterprises.

Some Philippine banks would rather pay the fine or over-allocate to medium enterprises than extend loans to micro and small businesses. (See Figure 2.)

(Figure 2)

The decline in loan allocations to MSMEs is probably a key factor behind the absence of a palpable impact of the credit upgrades on most companies and job creation. MSMEs comprise an estimated 99 percent of Philippine business enterprises, and account for 65 percent of eployment. As such, excluding MSMEs from a financial bonanza is tantamount to exlcuding the majority of Philippine jobs and companies from the benefits of an investment grade rating.

PHL trails in financial inclusion

The exclusion of most Filipinos from key markets – notably financial markets – has been a structural bane of the economy. The recently released Global Financial Inclusion Index (Global Findex), developed by World Bank economists, proves that only a small number of Filipinos borrow from formal channels.

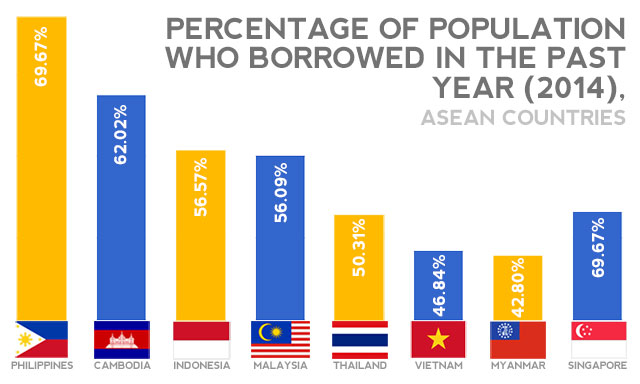

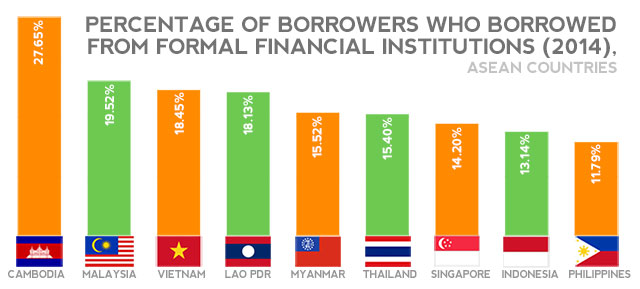

Despite having the largest percentage of borrowers among ASEAN countries in 2013 (see Figure 3), the Philippines was at the opposite end of the spectrum when it comes to borrowing from financial institutions (see Figure 4).

Of the 70 percent of Filipinos who borrowed money in 2013, only 12 percent obtained their loans from formal channels.

That means Filipinos seem to borrow more from informal lenders – friends, loansharks or relatives – a practice that is likely to be highly limited and at the same time very costly.

Nevertheless, some improvements have been made on the state of financial inclusion. In 2011, only one in four Filipinos owned a bank account – including mobile banking or other financial institutions – for savings, salaries, bills payments, or government transfers.

Three years later, the ratio increased to almost one in three Filipinos – representing roughly 6 million new accounts.

Policy innovations such as the Credit Information Corporation (CIC) can help solve some of the inherent challenges faced by lenders to small firms and borrowers. By aggregating both individual and corporate credit information, the CIC could help archive and disseminate the credit record of borrowers – thus improving access to loans as well as update lenders’ information on borrowers and help reduce the risk of default. Bottom line is that lending to these sectors become more financially viable.

(Figure 3)

(Figure 4)

Note: All values are for 2014 except for Lao PDR whose value is taken from 2011 data.

Source: Demirguc-Kunt, et al. 2015.

Letting investment grade work for every Juan

A closer look behind the recent excitement over the credit rating upgrades as well as the new malls, skyscrapers and the booming stock market reveals that many farmers and small entrepreneurs are still struggling to gain access to credit. Most workers still do not have insurance against income and health shocks.

For the majority of the poor and low income Filipinos who need to provide for their daily consumption, their only recourse seem to be the loansharks that charge exorbitant rates. They are the ones who actually need an upgrade in life – as for them an investment grade does not matter at this point.

The good news is that policies to dramatically improve financial inclusion could change the landscape, drive development and sustain inclusive growth. Innovative financial products, the entry of new financial sector players – notably from ASEAN – and stronger financial regulatory oversight could help jump start this structural shift towards greater financial inclusion.

In addition, the competitiveness (read: financial viability) of many enterprises could also improve under less onerous regulations and a more competitive and corruption-free environment in which entrepreneurs enjoy a signifincant ease in doing business.

The implementation of a competition policy and an anti-trust law could also level the playing field and spur the creation of more space for new and fast growing enterprises.

All these reforms should allow access to financial markets with more than a fair amount of success. – VS, GMA News

=============================================================================

R.U.Mendoza is Executive Director of the AIM Policy Center. Kath Peralta is a research intern at AIM. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Asian Institute of Management [nor of GMA News Online]. Further information on the data and analysis can be obtained here.

More Videos

Most Popular