Are we out of the woods?

Barely two weeks since the Philippines posted the fastest economic growth in the region for the first quarter of the year, the just-released 2016 World Competitiveness Yearbook (WCY) shows a marginal drop in the country’s ranking from 41st to 42nd place among 61 countries included in the report. This puts to question the weight of a country’s macroeconomic performance in determining its level of national competitiveness and its general attractiveness to investors.

The outgoing Aquino administration has been rightfully proud of the country’s recent economic boom and its growing prosperity. Sound fiscal and monetary policies have strengthened Philippine macroeconomic fundamentals, warranting numerous credit ratings upgrades, bringing the country to investment grade for the first time in 2013. These achievements, along with a proven resilience to external shocks, thanks in large part to a steady stream of OFW remittances and IT-BPM sector growth fueling domestic consumption and providing more than adequate dollar reserves, have resulted in greater confidence among businessmen and investors.

Unsurprisingly, the country saw huge jumps in its competitiveness ranking based on another popular annual report — the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report — that is based mostly (about 2/3 of its indicators on average) on an executive opinion survey. Exciting growth numbers and national income account figures have certainly sparked curiosity and gained higher opinion for the Philippine economic potential among the international business community, as reflected by the country’s steep rise of 40 places in the rankings from 2009 to the present based on the WEF survey of about 140 countries.

The country’s performance in the rankings based on the WCY during the same period, however, had not been equally stellar. From 43rd place in 2009, the Philippines hovered between 38th place to the current 42nd among 61 countries, fluctuating between 41st and 42nd in the last three years. Meanwhile, the country’s rank hovered between 11th and 13th place among 14 Asia-Pacific countries.

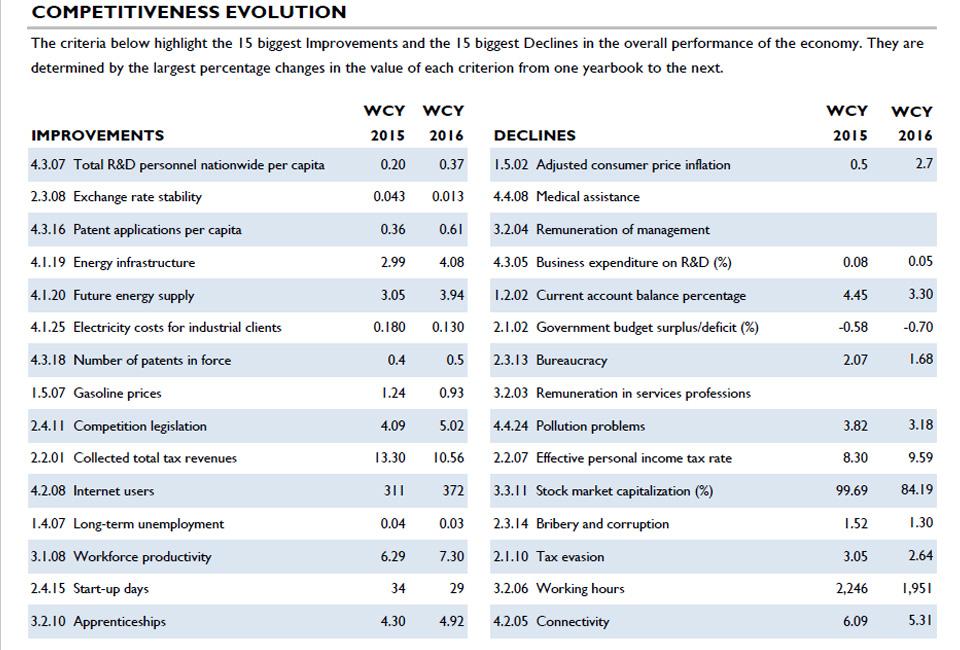

The WCY is annually prepared and published by the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) in partnership in the Philippines with the Asian Institute of Management’s (AIM) RSN Policy Center for Competitiveness. It is the world’s most comprehensive annual report on the competitiveness of nations, published without interruption since 1989. The global report uses international statistical data supplemented by an executive opinion survey of more than 5,400 to evaluate countries’ competitiveness over 342 criteria. About 2/3 of the criteria is measured using hard statistical data, while the remaining 1/3 uses opinion data to help quantify competitiveness issues that are difficult to measure like management practices, corruption, and quality of life. The report profiles each country’s competitiveness with respect to four broad categories: economic performance, government efficiency, business efficiency, and infrastructure.

Why has the Philippines failed to sustain significant gains in the WCY rankings? A very important lesson in sustaining national competitiveness may be drawn from recent developments at the top of the list. The United States, which held the top spot for three consecutive years, has been toppled by Hong Kong and Switzerland at first and second place, respectively. The United States still tops the criteria of economic performance and infrastructure, but it has lagged behind the two much smaller economies in terms of government and business efficiency.

In recent years, the Philippines indeed has show stellar economic performance, even outperforming global giant, China, in some indicators. But as the United States’ recent drop and the Philippine’s own lackluster performance in the rankings suggest national competitiveness involves much more than just GDP growth.

From 51st place in 2009 in terms of economic performance, the country jumped to a record 29th place in 2011, but meandered between 42nd and 38th in the next five years. Among the Philippines’ notable strengths are its GDP and GDP per capita growth, the resilience of its economy to external shocks, and its relatively stable exchange rate. The country’s low levels of GDP per capita, foreign direct investment, and export, however continue to drag down its performance.

Business start-up efficiency

While the country ranks second in terms of economic resilience, and fourth in real GDP growth, it trails behind at second to the last in terms of business start-up efficiency and foreign ownership of local companies, and ranks third to the last in terms of executive opinion on the efficiency of the customs authority in facilitating transit of goods. The country also continues to rank near the bottom in terms of perception of bribery and corruption, protectionism, tax evasion, and bureaucracy.

Strong macroeconomic performance has come in spite of these inefficiencies of government, partly due to exogenous variables like large OFW remittances, but these persistent inefficiencies continue to drag down Philippine competitiveness. Not enough foreign investors will come to the Philippines if they continue to face tall hurdles in ownership, start-up, and business operations. After all, a foreign investor, assuming that the law would allow him, might be far better off setting up shop in wealthy Singapore where it takes only 3 procedures or two and half days to register a new business, than in the Philippines where it takes 16 procedures or at least 29 days. It should not come as a surprise to see over 50 percent of FDI flows into ASEAN pouring into Singapore versus the 2.4 percent share that the Philippines received in the same period between 2009 and 2013. The WCY ranks the Philippines at fifth to the last place on the sub-factor of business legislation, which includes such indicators of the freedom and ease of doing business as mentioned above. One saving grace under this sub-factor was the notable improvement in opinion regarding competition legislation with the passing of the new Philippine competition law in 2015.

Also under the broad criterion of government efficiency is the sub-factor of “societal framework,” which includes indicators of income and gender equality, private property rights, and political instability risk. There was no improvement reported in the country’s ranking under this sub-factor. Overall, the Philippines’ rank in terms of government efficiency stayed unchanged from last year’s rankings.

The country’s ranking in terms of business efficiency saw a slight improvement from 26th to 24th place, primarily due to an increase in productivity, and improvements in perceptions of management practices and local attitudes/values. The gains in productivity however was in terms of “overall productivity real growth” estimated by the percentage change of real GDP per person employed, which expectedly posted a very high value relative to other countries given the Philippines’ remarkable GDP growth last year. The country’s actual level of overall productivity estimated by the GDP (PPP) per person employed remains second to the lowest. Same is the case for labor productivity. These results highlight the need to increase value-addition and value-creation across all sectors from agriculture to industry, and services, where productivity continues to remains very low in spite of the economic boom. Philippine productivity in services, for example, the primary driver of recent growth, is third lowest among countries studied, and its value is less than a third of the international average. This puts to question the nature of jobs in the fast-growing services sector in terms of their value-added. A relatively low labor force participation rate, which implies a heavy dependency ratio, and a continuing perception of rapid brain drain are also major challenges to business efficiency.

In contrast to the restrictive nature of the current legal framework over foreign ownership of domestic assets, and the perceived government and business rigidities and inefficiencies, Filipinos are highly perceived to have a “culture [that] is open to foreign ideas” (ranked 10th) and to be highly flexible and adaptable when faced with new challenges (ranked 3rd). These are strengths whose potential the Philippines has yet to maximize. If foreign businessmen actually want to work and do business with Filipinos, if not for the physical and legal hurdles they face, then government is doing a disservice preventing mutually profitable transactions from taking place.

One of the biggest hurdles investors face is the country’s inadequate physical and social infrastructure. Although the 2016 WCY reports an improvement from 57th to 55th place in the broad criterion of “infrastructure,” the country still ranks near the bottom of the list of 61 countries. The Philippines ranks lowest in terms of education at 59th place. The country also ranks very low in basic infrastructure, scientific infrastructure, and health and environment.

The country ranks lowest and second lowest in pupil-teacher ratio for secondary education and primary education, respectively. It also ranks very near the bottom in terms of secondary school enrollment, the human development index, and life expectancy at birth. Considering the Philippines’ reliance on human resources as a primary asset for its current sources of growth, there is an urgent need to start investing more rapidly in human capital. Considering also that the country largely benefits from its growing IT-BPM sector, there is also an urgent need to improve connectivity, and communications technology, both in which the Philippines ranks third to last. The countries strengths in terms of ICT service exports (ranked 1st), high-tech exports (ranked 1st), language skills (ranked 18th), management education (ranked 25th), and university education (ranked 26th) must be complemented with better basic education, basic physical and ICT infrastructure, for growth to be sustained. Otherwise, gains made in recent years may quickly erode as soon as businesses begin to realize that the economy and its underlying structures are not yet fully ready for take-off.

These are crucial times for a country on the verge of rapid development like the Philippines. Strong macroeconomic fundamentals and accompanying good spirits among businessmen and investors may be enough to get the country’s economic engine running again. If enough people believe in an economy, that economy is bound to start rolling soon enough. But in order to sustain that drive, inefficiencies must be addressed, rigidities cleared, and inadequacies filled. Otherwise, rosy perceptions will soon succumb to the persistent realities of the country’s stalling competitiveness.

======================================================================

The views expressed in the article are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Asian Institute of Management.

Jamil Paolo Francisco is Associate Professor of Economics at the Asian Institute of Management and Executive Director of the AIM RSN Policy Center for Competitiveness (formerly AIM Policy Center). His co-author is Emmanuel Garcia, an Economist of the AIM RSN Policy Center for Competitiveness. The authors would like to thank Nicholas Andrew Price for the research assistance. For questions and comments, please send your email to policycenter@aim.edu