Looking back at the past 50 years, how do we assess the status of women in this country, particularly in light of recent debates on the reproductive health (RH) bill? While women make up over half of the population and their contribution to society has clearly been incalculable, a disparity remains between the fulfillment of their needs, on the one hand, and the services and protections afforded to them by the state, on the other. Without a doubt, the institutional empowerment of women can be traced as far back as the Marcos era, with the establishment of the National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women (now the Philippine Commission on Women) in 1975, which served -- and continues to serve -- as the national machinery for integrating women into the economic and socio-cultural fabric of the country. Later administrations followed suit in acknowledging women as a priority, with President Corazon Aquino’s (Cory) Philippine Development Plan for Women; President Fidel V. Ramos’ (FVR) Gender and Development Budget and his administration’s grant of full representation of women in the Social Service Commission; President Estrada’s (Erap) Philippine Agenda for Women Empowerment; and President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s (GMA) Framework Plan for Women and Magna Carta for Women.

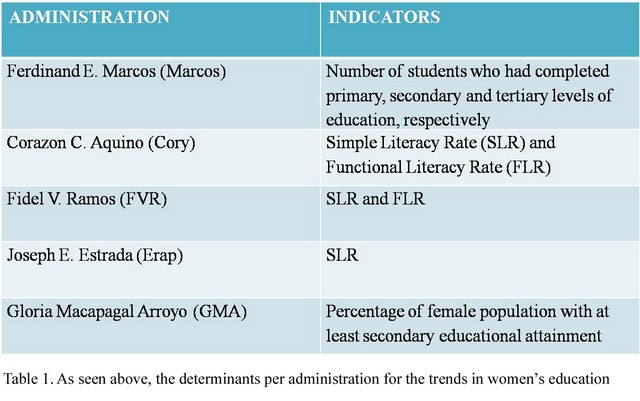

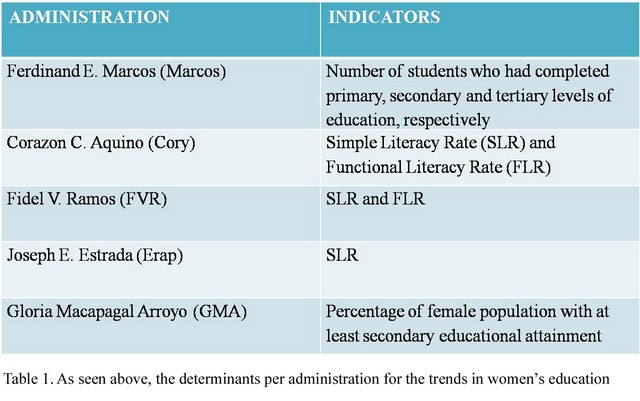

A fresh analysis: education, employment, violence against women and health At the outset, it bears mentioning that a significant problem in this country has often been not only the paucity of data but comparing data across time. In this case, each administration has tended to emphasize different indicators over others, and part of the challenge in assessing the changing status of women has been to find a common set of measurable indicators that remain meaningful in a comparative sense. Despite these limitations, what follows here is a brief examination of each presidential administration’s attempts to improve the welfare of women with respect to specific indicators of critical importance: education, employment, violence against women, and health – all of which demonstrate, in deeply fundamental ways, the integral part that gender has played in the developmental strategies crafted by each administration.

Education

Following

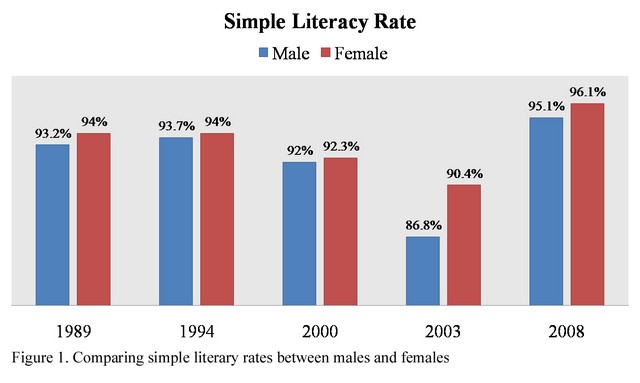

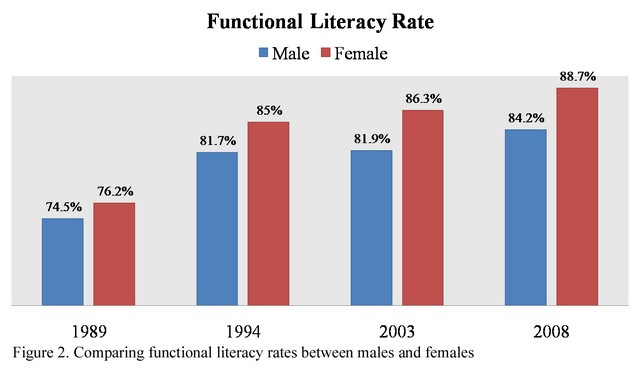

the definitions set by the National Statistical Coordination Board, Simple Literacy Rate (SLR) indicates a person’s ability to read and write while understanding a simple message in any language or dialect, while Functional Literacy Rate (FLR) assumes a higher level of literacy, including a grasp of numeracy, encompassing the overall ability of a person to use written communication in carrying out important activities in his/her life.

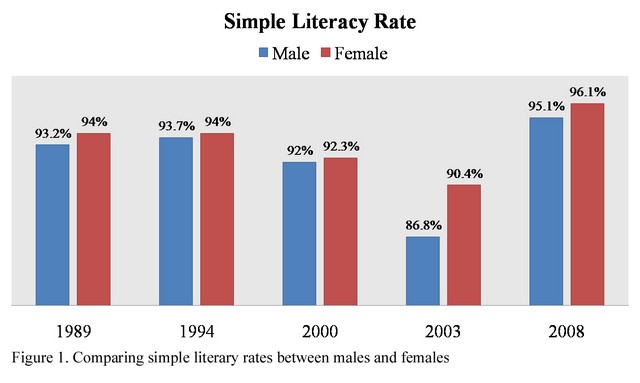

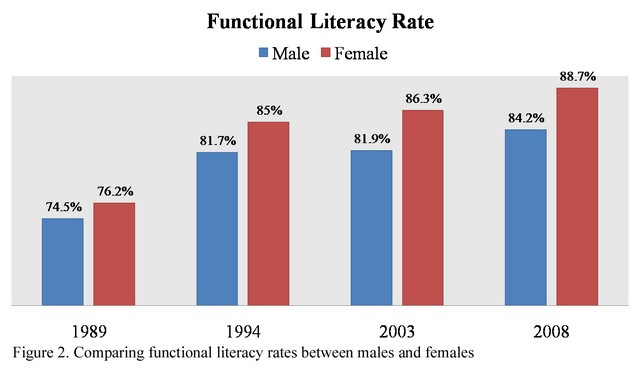

In the charts above, a striking pattern emerges, that of women's ability to outperform men in the acquisition of both simple and functional literacy. This has often been attributed to women's greater diligence in the primary and secondary years, and the tendency of boys to be involved in games, truancy, gangs, and other forms of social violence. However, additional data demonstrates that, in tertiary education, the gender disparity narrows because these also happen to be child-bearing years for many young women.

Employment

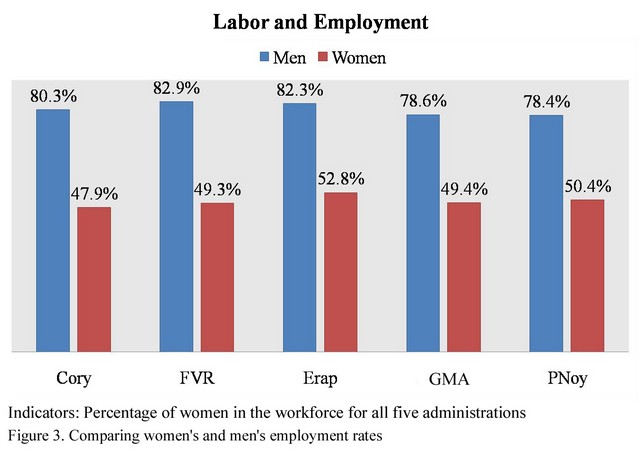

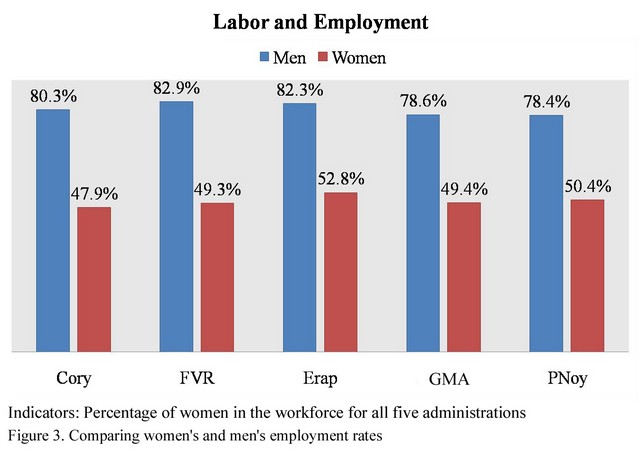

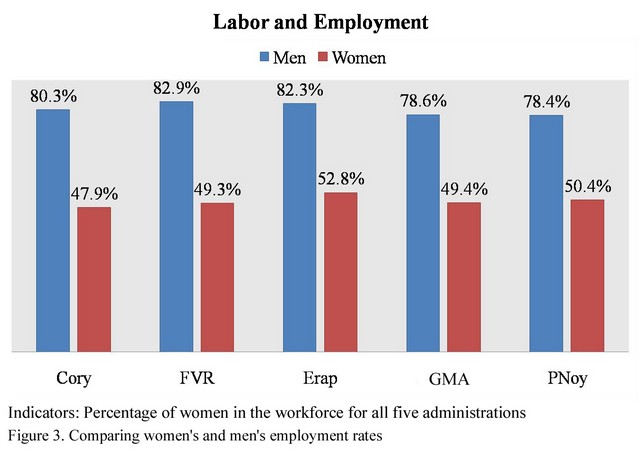

In the chart above, we observe a startling reversal. Women's consistent edge in literacy over men is subverted in the area of employment. Over time, women tend to lag behind men in the work force. How do we explain this persistent gap between the genders in employment rates through each administration? In addition to gender discrimination in many institutions, particularly in higher paying jobs, there are often inadequate facilities that would enable women to combine work and family responsibilities. Mismatches between education and the job market; forms of work-place inequities that keep women in and from certain kinds of jobs; high maternal and neonatal mortality rates; and cultural and economic pressures that compel educated women to stay at home and care for the family are among some of the oft-cited reasons. Under the Cory administration, a significant piece of legislation to address this gender imbalance came from former Senator Leticia Ramos Shahani’s amendments to the labor code. These were intended to strengthen the “prohibition on discrimination against women with respect to terms and conditions of employment,” which meant that a woman should not be discriminated against in terms of pay, training opportunities, and promotion. Under FVR, the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA)’s Women’s Center was established to train and strengthen women's proficiency in fields usually dominated by men. TESDA also sought to expand opportunities for community-based employment for girls who had only completed primary and secondary education. During the Estrada administration, the Philippine Agenda for Women Empowerment was inaugurated with a grant of PHP 3 billion to encourage women entrepreneurs. In line with this, President Arroyo duly highlighted the need to fight sexual discrimination in the workplace with the Magna Carta for Women, in addition to establishing a partnership with the Departments of Labor and Employment and Social Welfare and Development to deliver necessary services for female migrant workers. Still, despite all these measures, the gender gap in employment rates unfortunately persists as of this writing, presenting a continuing challenge to current and future administrations.

Violence against women Without doubt, the most vexing area of study has to do with actual violence, which women have to contend with on a daily basis. The Martial Law era was particularly notorious for many unrecorded cases of political imprisonment, torture, rape and killings that included countless women that remained nameless and faceless to this day. Violence against women included arrest without warrant, confinement, deprivation of basic needs, sexual harassment and abuse. In the wake of Marcos years, the Cory administration released political detainees, restored the writ of

habeas corpus and created the Commission on Human Rights. During the Ramos administration, the groundbreaking Anti-Rape Law (R.A. 8353) was finally passed (after eleven long years), with former Senator Leticia Ramos Shahani as its principal author. Prior to this law, rape had been defined as a crime against chastity, presenting daunting obstacles for women who hoped to press charges against their attackers. The new Anti-Rape Law reclassified rape as a crime of violence against persons, making it possible for anyone – male or female, gay or straight, virgin or not -- to lodge criminal complaints against their attackers. Under Arroyo, a new law (R.A .9262) further strengthened the law by adding children to the list of victims, and increasing the penalties for rape.

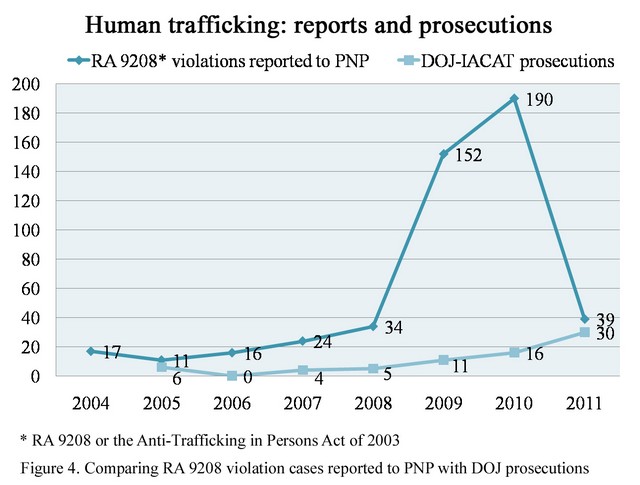

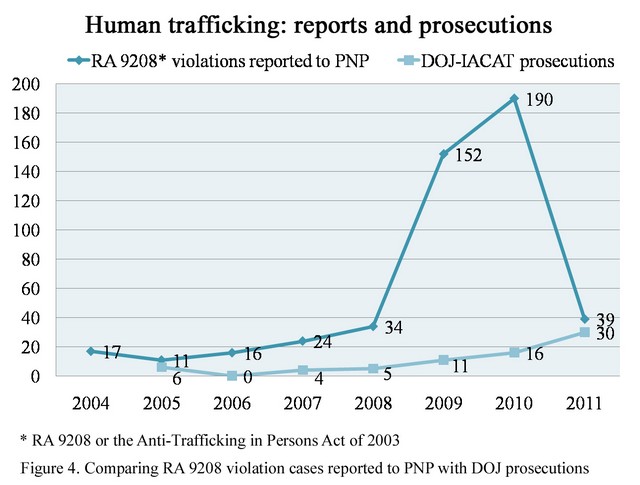

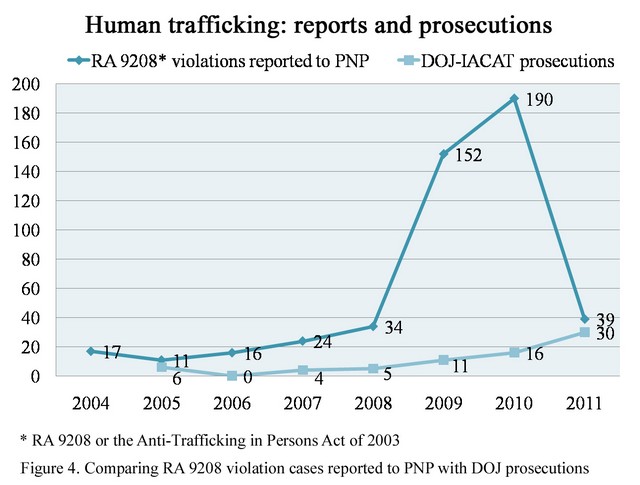

More recently, the passage of the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act in 2003 has had a significant effect in curbing illegal recruitment schemes. Seeking to halt the abuse and sexual exploitation of women, children and even men, this law has sought to abolish trafficking and sexual slavery. The graph above demonstrates the Department of Justice’s growing efforts to apprehend and convict persons guilty of trafficking offenses since 2004.

Health

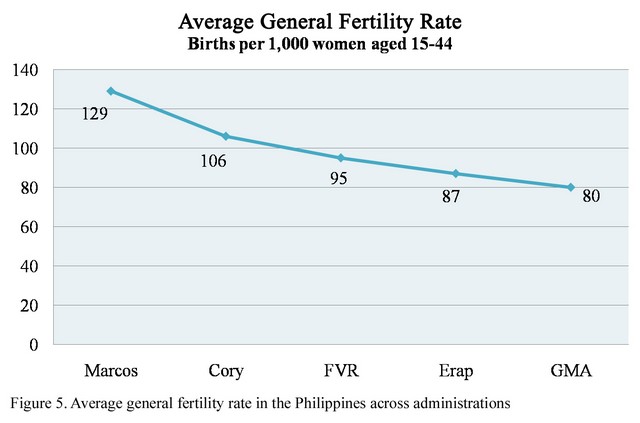

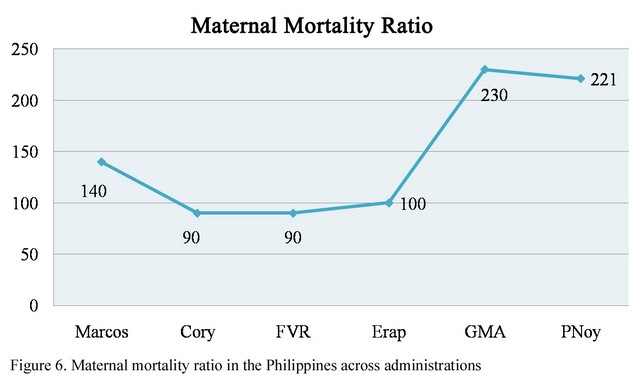

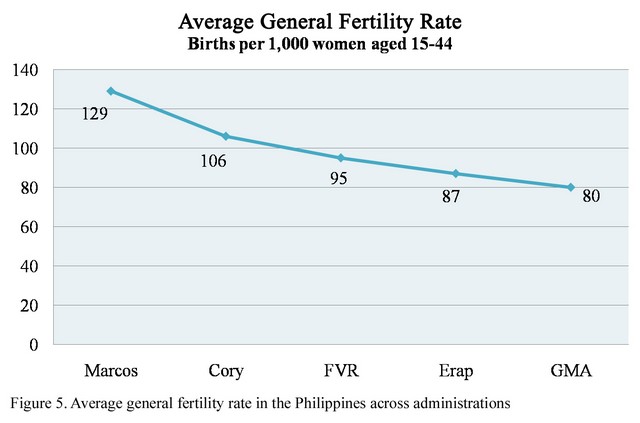

The focus on women's reproductive health has varied from one administration to another, particularly with respect to the issue of fertility reduction. Under Marcos, Presidential Decree 79 established the National Family Planning Program that sought to respect the religious beliefs of individuals. However, the Cory administration was heavily influenced by the doctrines of the Catholic Church, which opposed artificial birth control. Cory thus tended to focus primarily on maternal and child health issues at the expense of fertility reduction.

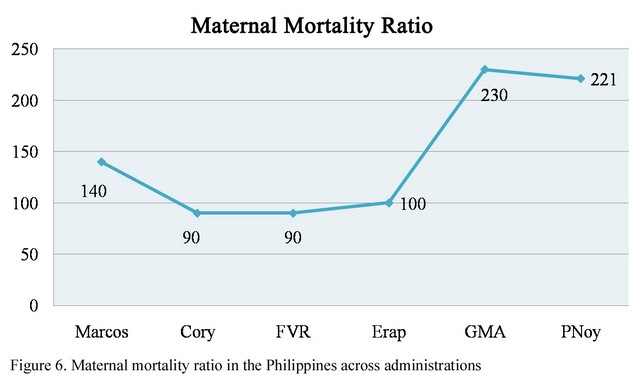

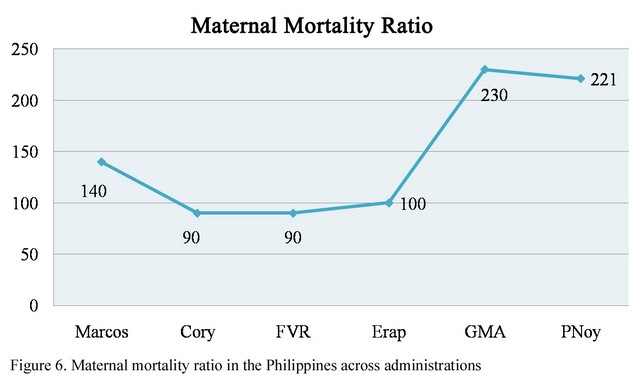

During Ramos’ tenure, the Medium-Term Philippine Development Plan was launched, directly addressing the issue of population growth, as well as the improvement of maternal and child health. In addition, the Department of Health released Administrative Order No. 1-A, detailing a comprehensive 10-element Reproductive Health Program. Under Estrada, family planning had originally taken a back seat. Erap was quoted in the newspapers as having said that he was against family planning, extolling the advantages of having a large family. Certainly, the Medium-Term Development Plan of 1999-2004 did not include strong policies to moderate population growth, nor did the implementation of a family planning program address fertility reduction. To address this, National Economic Development Authority Director-General and Commission on Population (PopCom) Chair Dr. Felipe Medalla and Department of Health Secretary Alberto G. Romualdez, Jr. took the initiative to reshape the Philippine Population Management Program for 2001-2004 to include a more robust family planning policy. But Estrada’s term was short-lived, as were, regrettably, the terms of the PopCom board members. More ambiguous were President Arroyo’s policies on family planning as a means to curb population growth. Although she acknowledged the problems of uncontrolled population growth, her administration’s family planning program focused less on fertility reduction and more on neo-natal and children's health care, as well as natural family planning methods.

What remains to be done? Clearly, although significant progress has been made in the status and welfare of women over the last fifty years, many challenges remain. Gender equity in education continues to improve, with records from the Commission on Higher Education noting a comparison of 57.44% female graduates (269,748) versus 42.56% male graduates (199,906) in the Academic Year 2009-2010. However, women still lag behind men in employment — despite a rise in the percentage of professionally licensed women in 2010 at 63.7% over men’s 36.3%, men’s employment in 2012 is still significantly higher at 78.4% over women’s 50.4%. The socio-cultural explanations for this astonishing reversal have already been discussed above. But what this trend clearly underscores is the fact that our educated women remain seriously under-tapped in this growing economy. An even more pressing concern is the continued violence against women throughout the country. A laudable achievement, however, is that the Philippines is now at Tier 2 Status in the Global Trafficking in Persons Report, no longer in the notorious Tier 2 Watch List Status, which means our international partners now recognize the vigorous efforts both government and civil society have made to combat human trafficking at home and abroad. Another positive development has been the passing of the Kasambahay Bill (H.B. 6144) in the House, which protects the rights of the 1.9 million domestic workers in this country. But a recent law decriminalizing vagrancy (R.A. 10158, or the revision of Article 202 of the Revised Penal Code), sponsored by Senator Chiz Escudero and Representative Victorino Socrates has had unintended consequences on women. Regrettably, female prostitutes (unlike male prostitutes and vagrants) continue to be criminalized, while men who participate in their exploitation are not held liable for prosecution. This lack of protection afforded to female prostitutes is in conflict with the Magna Carta for Women and the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act, which mandates the protection of women from abuse and violence. A more nuanced Anti-Prostitution Bill that targets the demand side by criminalizing those who exploit and engage in prostitution and human trafficking would have a far-reaching impact in the protection of women from violence. As of this time, there are pending versions of this bill in the House and Senate, which greatly needs public support. In terms of health, our maternal mortality ratio remains high at an alarming 221 per 100,000 live births, while HIV rates have been increasing with a 37% rise of documented cases in the past two years. And, last but not least, the Reproductive Health (RH) bill has become absolutely critical for this nation. Passing the RH bill would empower women, especially those in the poorest sectors with the highest fertility rates, allowing them to make all-important choices for themselves and for their families. Indeed, the Aquino administration has been unwavering in its support of reproductive health and responsible parenthood, regarding these as crucial elements in the pursuit of national development. In the final analysis, reproductive health empowers a woman in deeply significant ways since the proper interventions could determine whether she will finish tertiary education or not, can get better jobs in the job market, can combine home and work, will ever break the glass ceiling if she is genuinely gifted, will survive childbirth, and can live a life free from violence. Which means that reproductive health is not only a health measure, in the end, but an anti-poverty strategy that ultimately hopes to empower women and set them free.

Assistant Secretary Lila Ramos Shahani is Head of Communications of the Human Development and Poverty Reduction Cabinet Cluster, which covers 26 government agencies dealing with poverty and development.