After 11 days in the hospital, a bout of pneumonia and a major scare, I think I can now be called a COVID-19 survivor.

I know of a few others, all attempting to return to low-profile lives in a fearful world, but most choose to remain invisible. There are strong reasons for this anonymity. This disease is one of the most stigmatized and loneliest in human history, perhaps comparable only to leprosy where quarantine can be forever.

One of my fellow COVID-19 patients in the hospital can’t go home because his condo building won’t let him move back, despite already testing negative for the virus.

I am one of the lucky ones who have been able to go home, resume a semblance of my former life, and live to tell the tale.

It’s a tale of long painful needles that couldn’t find a vein in my hands, the swabs down my throat that made me gag, the torture of long sleep deprivation, and the team of doctors who formed a Viber group to discuss updates on my case and the experimental drug chloroquine that worked on patients elsewhere and eventually worked on me.

Since the pandemic is far from over, many more will be infected and confined. Some will not make it. Those of us among the pioneers — I’m Patient 2828 in the lower part of the curve - have a responsibility to talk about this experience in a way that will enable the public to understand it, lessen the fear, and create compassion for those who survived COVID-19.

A few takeaways:

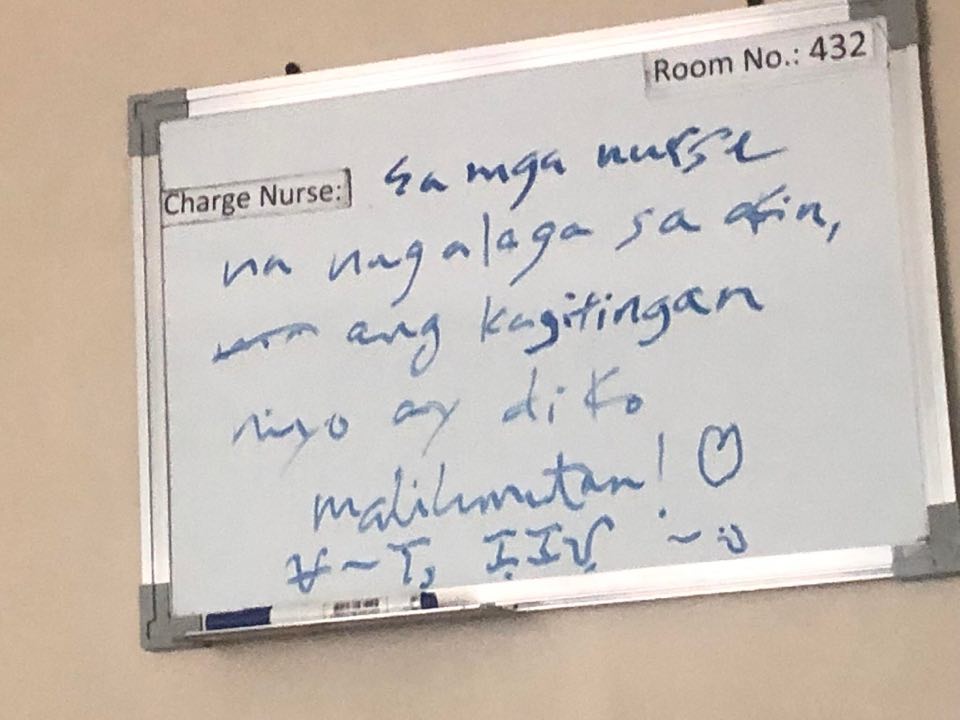

It will be hard to pay them back, but one can pay it forward. If it’s true that I will have antibodies in my blood that can help others fight off infection, I’ll be glad to donate this accidental gift. It’s a small price for all survivors to pay for the chance to see the sun again.

Very often when alone in my room, I’d gaze out of my window into the empty streets, the trees, and a giant bas relief of the Philipppine map displayed in a dry fountain in the hospital’s parking lot. It reminded me of a world I was eager to rejoin.