By ANNA FELICIA BAJO, DONA MAGSINO, and JOVILAND RITA

January 21, 2021

The new setup would have been much easier if his wife were still here.

Widower Miguel Sobrepeña, 46, lives in Magallanes town in Cavite with his two children. His eldest Hannah is in Grade 8 while the youngest Shekinah is in Grade 4. And with both kids having to deal with distance learning while the COVID-19 pandemic rages on, Miguel is reminded of the bitter reality that his wife Mylene, who died due to a blood clot in the brain in 2018, is no longer around to help him raise their children.

“I’m finding it difficult,” Miguel said in Filipino, two weeks after the school year opened in October. “When my wife was still alive, it was easy because she helped me teach the kids. Now, I have to juggle teaching them and working so that I can support them. I now appreciate what she did when she was still around because her presence makes a difference.”

As if being a single parent weren’t difficult enough, Miguel also lost his most stable source of income last September, a month before school resumed. He had been working as an administrative aide in their barangay hall, receiving a monthly honorarium of P3,600 from that day job, before a disagreement with an official.

Miguel has bright hopes for Hannah, who studies in a private high school after receiving a scholarship. But with the distance learning setup, there are many expenses that quickly add up.

“She’s on a scholarship but we still pay P300 a month for her modules. I pay monthly because I cannot afford paying the full price of P3,000 for the whole year,” Miguel said.

After losing his job at the barangay, Miguel began to work at a funeral parlor — the same one which provided service for his wife’s wake. “I’m like an agent. I only earn commission depending on the number of clients I get,” he said.

He also tends a portion of land that his farmer parents gave him. The coconuts, root crops, bananas, and cashew add an additional P2,000 to their monthly budget during harvest season. They also get a P2,700 death benefit pension that Mylene left behind.

Because Hannah has to communicate with her teachers and classmates online, she needs internet connection. Families in the compound where they live agreed to get an internet subscription, dividing the monthly cost depending on the number of gadgets per household. Miguel shells out P300 monthly for this internet connection since they have two cellphones in use.

Studying at home presents challenges because distractions are just one click away.

“It’s one of my major concerns because Hannah loves watching anime on YouTube. She’s not into gaming but she watches videos,” he said. “I noticed that when after she’s done answering her modules, she would watch YouTube. She’s rushing to finish tasks so that she could watch. I’m not sure if her access to the gadget is a good thing for her. I would take it away but I would feel bad.”

The bigger burden for Miguel, however, is having to be there the whole time to help the kids with their schoolwork. “It’s lighter for me that the children are not asking for school allowance. But when they were attending school in person, the only extra work I had to do was just to bring them lunch and help them answer their assignments. Now, everything is on the parents’ shoulders,” he said.

A graduate of a vocational course in electronics, Miguel has taken to Google as his go-to move since the classes of his children began. He tries to search for the lesson online whenever he cannot understand the self-learning modules that his 10-year-old daughter Shekinah studies in the public elementary school.

Some subjects take longer for Shekinah to understand. “When we begin at 8 a.m. and especially if it’s math, we’d end at noon. Because of course, you need to analyze. I’ve also had to adjust because it has been a while since I was in school. There are some things you could still recall, but there is a lot I really don’t know.”

Miguel Sobrepeña spends hours helping his youngest daughter Shekinah with her school modules. A widower, Miguel is alone to help his two daughters with distance learning.

Miguel gets a bit of help from Shekinah’s teachers, who make themselves available in a group chat on Facebook. But because of the volume of questions from parents, not all questions could be answered.

“If you don’t understand a lesson, you could take a picture of the module and send it to the teacher. But sometimes with the number of parents with questions, once you ask, everyone else will ask,” Miguel said.

Shekinah also answers weekly activity sheets but Miguel has apprehensions about these. “Parents handle the quizzes. My concern there is that teachers send the answers to the group chat. If a parent wants to cheat so their kid won’t be out of the honor roll, they can just give their children perfect scores. When you submit the modules, teachers would just look at those scores.”

Teachers, meanwhile, check the weekly assessment tests themselves.

Miguel is far from alone when it comes to dealing with learning modules — and all the issues these entail.

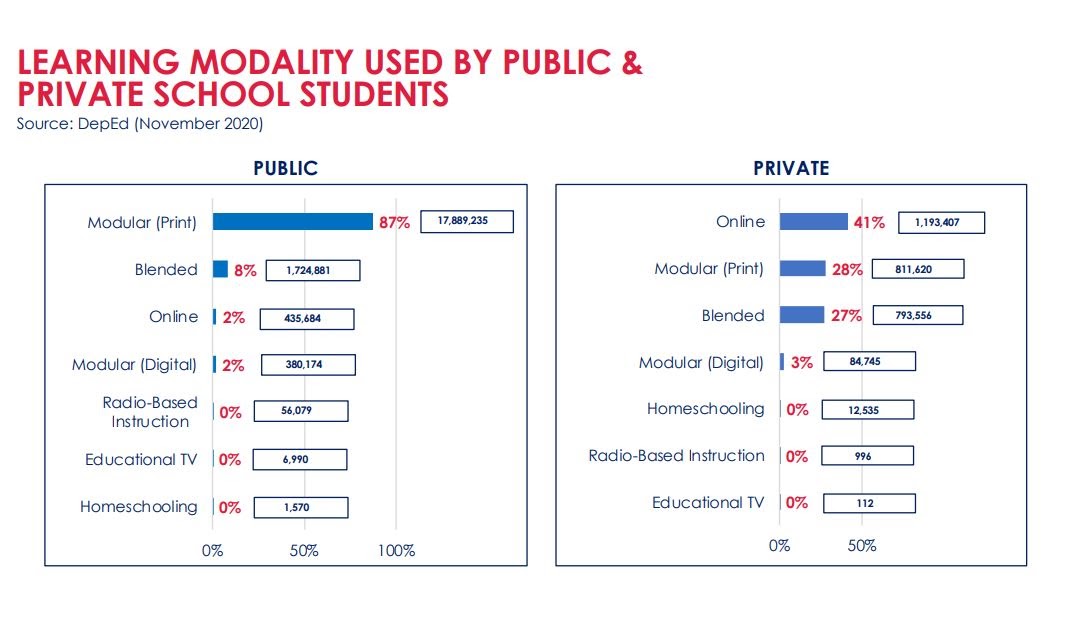

Based on DepEd data presented by the Senate Committee on Basic Education in November, around 17.9 million public school students in the country depend on self-learning modules.

On the other hand, more than 811,000 of the two million learners in private schools rely on these printed learning materials. The online platform remains the top modality used by private school students, whose families could afford it.

Data from the 2017 Annual Poverty Indicators Survey of the Philippine Statistics Authority shows that only 22.4% of households in the country have their own personal computer. On the other hand, 87% of households had a cellular phone. Some 91% of families in the higher income households, and 77.7% of low-income families had at least one cellular phone.

Recognizing the unequal access to gadgets and connectivity, Education Undersecretary for Curriculum and Instruction Diosdado San Antonio said the DepEd provided modules to almost all 22 million enrolled K-12 students in the country.

“In the first quarter, the regional offices said they distributed modules to almost all the students because they want to make sure that there is this support even if the learners were doing other distance learning delivery modalities. They reproduced for all, just for transition,” San Antonio said.

Eight weeks into the school year, Miguel has gotten the hang of the new learning setup for his children, but he said it was exhausting.

“I’m not a teacher, what I learned in school is not enough for me to teach the lessons of my kids. If it were up to me, I would really prefer face-to-face classes for them,” Miguel said.

His older daughter Hannah also helps out with Shekinah’s lessons when Miguel is working on the field.

Asked if he thinks his children are learning something through the modules, he said: “The children are learning but it depends if the parents are really determined to teach them. If the parents are not eager to teach, the kids will not learn.”

Marina (center) helps her five children (L-R) Carlo, Jenier, Godwill, Rona, and Jonathan answer questions from the school modules at their home in Baras, Rizal. Photo: Rea De Guia

After graduating from daycare, Rona was supposed to start kindergarten at the big elementary school to begin the new school year.

But when told that she would have to take her lessons inside their home in the middle of a woodland in Baras town in Rizal, Rona told her mother Marina she didn’t want to study anymore.

Marina had to explain to Rona the dangers of the coronavirus. But while she eventually understood the situation, the five-year-old peppered her mother with questions: When can I go back to school? When will I be with my classmates again?

With no clear answers, Marina helps Rona go through her modules. Marina would read Rona each question — the little girl did not know how to read yet — and would have to explain again if the child could not fully grasp it the first time.

For the 33-year-old mother, helping Rona with her lessons is actually the easy part. She also has to assist four other children with their lessons: Jenier, Jonathan, Carlo, and Godwill.

Grade 1 student Godwill is set to study three hours a day to finish at least seven pages of his modules in three subjects — Filipino, Science, and Math — with questions about the construction of sentences, the parts of a tree, as well as the addition of numbers.

He could sometimes finish the activities in the modules of only two subjects. Marina pushes Godwill to finish the activities in all three subjects, as instructed by his teacher. While he would finish some activities by 1 p.m., there would be times when he would have to extend, which cuts into his playtime.

“I’d rather be in school,” Godwill said in Filipino about having to study at home. “I’m not happy.”

Like with Rona, helping Godwill with his lessons is easier for Rona, because a lot of the subjects are like a review of lessons from kindergarten. All Marina has to do is read the question to her son and correct him when he gives the wrong answer.

But this is far from the case with her other children at the Grade 4, Grade 5, and Grade 7 levels, all of which have complicated lessons and activities. Marina lamented that as the grade level gets higher, the lessons and activities in her children’s learning modules get more complicated, leaving her and her husband to face “challenges” in understanding and explaining these to their children.

“The situation today with school is different. Unlike in the past — now there’s so much to learn at school,” Marina said in Filipino.

Grade 4 student Carlo starts his activities at around 9 a.m. after finishing his household chores, like washing the dishes. With modules from eight subjects to get through every day, Carlo often has to extend his study hours until the evening. “So I won’t be late when it’s time to submit,” he said.

He thinks he’d be able to absorb more if there were a teacher to explain to him the lesson. He said he is only learning a few things through the modules, and he has a hard time answering the questions in the activities. When he gets tired answering his modules, the 10-year-old boy said he would push himself. He no longer has any time to play.

Marina said her children spend nearly all their time and focus in answering the modules. Like Carlo, Grade 5 student Jonathan takes until night to finish his modules in eight subject, with five pages for each.

Carlo would sometimes find instructions and questions in the modules unclear and confusing. The 10-year-old would ask his mother to explain them to him but sometimes, even Marina cannot comprehend the text in the modules.

It is a tough thing to ask for Marina, who had to stop school at Grade 7. Her husband Sammy only reached Grade 6.

Life also tends to get in the way. Aside from helping her school-age kids with their lessons, Marina also takes care of her two-year-old baby. When she is busy, one of the older kids would babysit the toddler.

“I am already tired. I still have to cook. I have a two-year old toddler to take care of. Do the laundry. I still have to persevere so my kids will learn. I have to sacrifice everything for the sake of my children,” Marina said.

The Philippines recently scored lowest among 58 countries in fourth-grade mathematics and science, according the 2019 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS).

The Philippines performed the poorest out of 79 countries in a reading literacy assessment among 15-year-old learners in the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

The 2019 Southeast Asia Primary Learning Metrics also showed low ratings of proficiency in writing, reading, and mathematics among Filipino students.

Grade 7 student Jenier tries to help, but also has to get his modules done for eight subjects: Edukasyon sa Pagpapakatao; Filipino; Araling Panlipunan; Music, Arts, Physical Education, and Health; Technology and Livelihood Education; English; Science; and Mathematics.

All modules need to be submitted on Saturday, while a new batch of learning materials are delivered on Monday. Jenier thinks the school should give students an extension in submitting modules, in consideration of those who are having a hard time answering the questions. Often, the deadline is only being extended by a few hours.

Aside from answering the modules, Jenier said there is no way for him to better understand the lessons. He admits he is just completing his module out of compliance with school requirements.

“I can barely learn anything, because the classes are not face-to-face,” he said.

The experience of students like Jenier is a red flag for an educational system that is already lagging behind. The Philippines recently scored lowest among 58 countries in fourth-grade mathematics and science, according the 2019 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS).

Senate Committee on Basic Education chairperson Sherwin Gatchalian noted this follows "dismal results" for the Philippines in other international assessments.

The Philippines performed the poorest out of 79 countries in a reading literacy assessment among 15-year-old learners in the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which was conducted by the inter-government group Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),

The 2019 Southeast Asia Primary Learning Metrics also showed low ratings of proficiency in writing, reading, and mathematics among Filipino students.

According to the study, the Philippines has a limited number of Grade 5 students who achieved higher levels of proficiency in writing. More than 70% of these students, meanwhile, were in the three lowest levels of writing proficiency. The weakest performers have only limited ability to present ideas in writing. Researchers noted that even the highest performers can only produce very limited writing, with simple, insufficient ideas, and limited vocabulary.

For reading, the results indicated that only a small to a modest percentage of Grade 5 children in the Philippines had achieved a level near the expected reading proficiency at the end of primary education.

Meanwhile, for mathematical proficiency, the Philippines raised a modest percentage of Grade 5 children who had achieved the mathematical literacy skills expected from the students. According to researchers, the majority of these children are still working toward mastering fundamental mathematical skills.

With these already dire observations, researchers have warned Southeast Asian countries in general that they will face aggravated challenges ahead in children’s learning due to the current COVID-19 pandemic as well as the subsequent economic downturn in the region.

Gatchalian thinks select areas in the Philippines that are low-risk for COVID-19 should be allowed to hold tutorials. Citing information from the University of the Philippines endCOV tracker, he said there are 496 municipalities nationwide with zero COVID-19 infections as of November 22.

“We should already allow limited community tutorials so that the children will have interaction with their teachers. If we are allowing 50% in churches, if we are allowing 50% in restaurants, you should at least allow 50% in community tutorials,” he said, noting that precautionary measures such as wearing of face masks and social distancing would still be followed.

“Allow the teacher to go to puroks and communities to do face-to-face tutorials. At least there is once or twice a week interaction with your teacher.”

Gatchalian said this would also help ease the burden of parents who are having a hard time teaching their children at home.

The Department of Education has pushed for a limited return of face-to-face classes in some areas free of the pandemic. In December, President Rodrigo Duterte approved a plan for a dry run for face-to-face classes for January. Over 1,000 schools were supposed to be evaluated for the possibility of holding physical learning activities again.

But the plan was shelved following reports of a more contagious COVID-19 from the United Kingdom. Duterte retracted his go-signal for the reintroduction of face-to-face classes a day after Christmas.

That leaves parents such as Marina with literally no answers for her children when they struggle with their modules.

Sometimes, she would be able to reach their teachers on her phone.

“I’m able to speak to them sometimes. I would call, sometimes text. Whatever my kids need to finish, I would sometimes call or text. But sometimes, like with this typhoon, there would be no signal. Sometimes, they’d text back,” Marina said.

“They would tell me to come down to the elementary school for a meeting. The teachers would always remind me to guide the kids because they’re not there. It’d be better if the children directly go to school, but the President already made the decision in this situation.”

The series of typhoons that battered Luzon from late October to early November destroyed Miguel Sobrepeña’s crops, which were supposed to his source of income in the early part of2021.

Though the distance learning activities of his daughters had been suspended by local government authorities at those times, Miguel said they continued to answer modules because there were instances when the submission deadline were not adjusted.

While Miguel’s family was spared from floods, over a million others in Luzon were not after Typhoon Ulysses struck several provinces. The Bicol Region was among the areas badly-hit.

Joshua Oyon-Oyon, a Filipino teacher in Sorsogon, said most of the modules of students, especially those in Catanduanes, were destroyed by the typhoons. This, unfortunately, delayed the classes.

“You need to repeat reproduction, printing. We had a lot of delay, we are only at Module Two because we had three storms in a week, and we had to wait several days before power was restored. We have 15 modules for Filipino. Imagine we end the first quarter on December 12, so we have to do a lot of modules to catch up,” he said.

The estimated cost of education infrastructure damage due to Super Typhoon Rolly and Typhoon Ulysses was over P10 billion, according to DepEd. This does not include non-infrastructure damage to school furniture, learning materials, and computers.

The department has promised to release additional funds for the reproduction of learning modules destroyed by the storms. There is also additional budget for hygiene kits and to conduct clean-up drives and psychosocial first-aid to affected schools across the country.

But what if the storms also damaged the students’ homes, where they were supposed to do their learning in lieu of face-to-face classes? This is the bigger concern, according to Senator Sherwin Gatchalian, the basic education committee chairperson.

“The problem I see with the typhoon is the concentration of the child, because in some areas, they’re still in evacuation centers, in some areas they have to clean their houses, in some areas their houses got completely washed out, so the child’s concentration and the stress surrounding him is the issue. I think that will be a problem that our teachers will consider and be proactive in,” he said.

“Before, I observed, when there was a storm, if the school is still standing, the child can go to school and learn. For example, your house got destroyed and your parents are slowly rebuilding the house, the child can still go to school and can see his classmates, and interact. The child is developing and learning but right now since there is no school and then you have no house, it’s a lot of stress for the child,” he added.

Due flexibility has been given to schools divisions affected by the typhoons, according to Education Undersecretary Diosdado San Antonio. DepEd regional directors were allowed to suspend distance learning activities in their jurisdictions.

Teachers in both private and public schools have also had to make adjustments after the COVID-19 pandemic left their classrooms empty.

Joshua Oyon-Oyon, who teaches Filipino in Sorsogon National High School (SNHS), said public school teachers are drowning in tasks and overwhelmed with additional responsibilities in the absence of face-to-face classes.

Teachers, he said, had so little time to create modules for students. In fact, he blames this for why there are numerous social media posts going viral because of errors in the modules.

“There’s really is a lot of errors, maybe because there was little time, it was rushed so kids would have something to use,” he said.

According to Joshua, teachers were forced to create modules because the ones that were supposed to come from the Department of Education’s central office are not yet available as these are still undergoing validation.

“They gave us a Google Drive with the modules, particularly Filipino, because Filipino is my field. They gave us then took it back, we can’t access because of copyright reasons. There were copyright problems, I think,” Joshua said, speaking to GMA News Online in November, more than a month after classes opened.

“Until now, the validation is ongoing, the proofreading is ongoing because I think there are still errors. Until now there’s no download from the central office, teachers had to develop the modules.”

Education Undersecretary Diosdado San Antonio acknowledged that there had been bottlenecks in the release of central office-produced modules because of the rigorous process for quality assurance.

“If the central office quality-assured modules have not arrived yet, you can prepare your own, print your own. Even when the materials from the central office are available, the schools can use the ones they have developed. Again, we are respectful of their professional judgment, so we allowed,” he said.

Many of the printed modules were produced at the local level, making it prone to some errors, according to the DepEd official. “In the first quarter, there are more locally-developed modules — either they have region-wide, division-wide, or school-wide modules. If you look at the reports submitted to us, those crafted in lower levels have higher number of errors because of limited quality assurance processes,” he said.

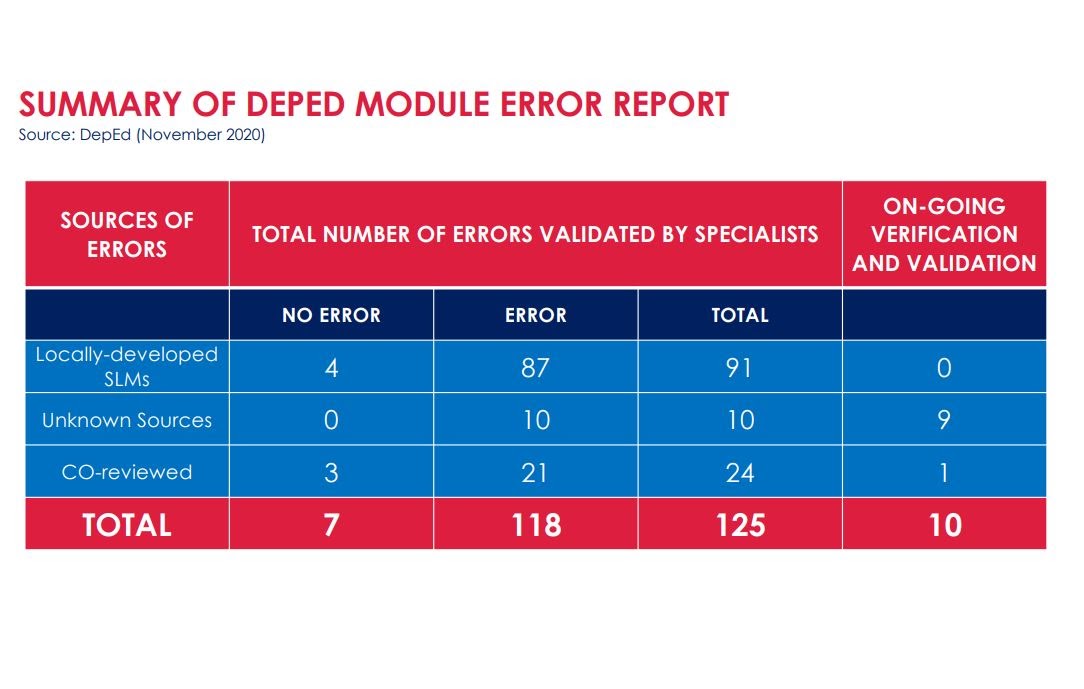

Data presented by Senator Sherwin Gatchalian during a hearing showed 118 errors validated by specialists as of November 20. Eighty-seven were identified from locally-developed modules, 21 from those reviewed by the DepEd Central Office, and ten from still unknown sources.

Moving forward, San Antonio said the DepEd plans to engage private publishers and academic experts from universities in the production of modules for the third and fourth quarters.

Department of Education Module Error Report, as of November 20.

Despite the lack of time, teachers were still able attend a series of training as part of the school’s preparation for this unusual academic year. However, some teachers, especially older ones, are still having difficulty especially with the use of technology.

“It was tough, especially for seasoned teachers, they had to make a lot of adjustments. When it comes to content there’s no problem, they can always teach, but of course it’s highly-technical when you’re using online platforms, online classrooms, Google meeting,” Joshua said.

“Even though we had capacity training, even then, it was tough for they. They’re digital immigrants. Even when you teach them, it’s tough.”

Aside from lectures and training, the school also provided some laptops and tablets to the teachers. Not all SNHS teachers got gadgets due to scarce resources. Teachers who did not own any gadgets were prioritized by the school.

Beyond creating modules and teaching online, teachers are also in charge of sorting, printing, and distributing learning materials to students. Joshua said teachers are lucky if their school has enough budget for the production of these modules because if funds are not sufficient, they will be forced to print and deliver learning materials using money from their own pockets.

It would have been better if the school could have a designated delivery person for the modules, or at least provide service for the teachers, he said.

“I even have a student residing on an island here in Sorsogon. It’s very difficult… I have to ride a boat just to bring the modules,” he said.

Despite being discouraged from going to school, some SNHS teachers are still holding their online classes at school due to internet connection problems in their homes.

SNHS is located in the city of Sorsogon. The capital of the province of Sorsogon has thrived compared to other municipalities and towns, but internet connection remains an issue, which affects the distance learning.

It’s an issue that bugs teachers around the country. According to the Speedtest Global Index, a service that tracks internet speed data globally, the Philippines ranked 110th out of over 190 countries for mobile speed and 103rd for fixed broadband speed in November 2020.

An overwhelming majority of public school students in the Philippines depend on print modules for their distance learning.

Amid all these, Joshua is not certain if students are really getting anything from distance learning. Whenever he checks the answers of his students, Joshua often has doubts if it was really his students who answered their activity sheets.

It could have been the students’ parents or siblings, Joshua said.

“Modules usually have keys to correction… it’s self-learning. But even with self-learning, sometimes they wouldn’t answer themselves, others just copy the answers,” Joshua said. “Most just tolerate at home so that students have something to submit.”

Other times, Joshua would find answers purely copied from the internet.

“I noticed that in some outputs I had checked, students just copied their answers from Google. We cannot control students because internet access is free. They can easily access it. Students usually look for answers over the internet, especially if they do not understand the concept of the lesson,” he said.

San Antonio said there is no specific protocol on sanctions for such cases under the new set-up, but DepEd is confident that public school teachers can handle these cases.

“Everybody is a professional. We all have licenses, even the teachers. We expect that they should know how to deal with such instances,” he said.

For Joshua, it would have been better if classes had not opened this year. The education sector, he said, lacked preparation with this learning scheme.

“I think what is happening now is just about being compliant with school requirements. Students answer their modules for the sake of submitting them. Teachers no longer measure if students get something from answering these modules,” he said.

But Gatchalian, the Senate basic education panel chairperson, said an academic freeze is not an option.

“Those who are calling for academic freeze don't appreciate the repercussions of regression because if a child will not go to school for a very long time, that child will regress, definitely,” he said.

“When we say regress, what he has learned in the past would definitely be erased in his mind or he would not remember what he has learned in the past. It’s important that we stimulate the minds of our children.”

Gatchalian warned that regression could also lead to higher dropout rates in the country. “For example, we go back to the normal face-to- face and they go to school and they experience difficulty in catching up, most likely they will drop out.”

This, he says, would lead to longer term problems for the Philippines.

“It’s a problem of our nation because the majority of our workforce in the future will come from public schools. Eighty-five percent of our students are in the public schools. So if our public schools will not perform, rest assured that our country will have a big problem in the future in terms of competitiveness, in terms of innovation, in terms of capable workforce,” he said.

The experiences of public and private school teachers in the pandemic is vastly different. Implementing adjustments is a common denominator.

Ronnie (not his real name) teaches Mathematics in one private school in the City of Mandaluyong. As early as May, the school started its preparation for school year 2020-21 despite the uncertainty of whether classes will resume.

“Even when we were under ECQ (enhanced community quarantine), we had previews, like tests. They were testing how to conduct online classes. So as early as May, there were surveys,” he said.

The department had originally set the opening of classes on August 24, but moved it to October. But accredited private schools had the option of opening ahead of public schools.

One of the main tasks of private school teachers like Ronnie is to create instructional videos for students. “The content of instructional videos must be original and not copied from other sources,” he said.

Some of them had no laptops or personal computers to use for online learning, so the management of the school provided them with gadgets.

They also had to prepare modules to serve as guidelines for parents who are not familiar with the online learning scheme. “Just to guide the parents in the event they lose connection. It’s more for use as a core syllabus,” he said.

Some older teachers did not know how to create instructional videos.

“All they knew was Powerpoint. They don’t create videos. They’d just create Powerpoint, they’d just enrich them, like they’d have longer explanation. So that’s one of the challenges,” he said.

The school’s management offered some training on making instructional videos in order to assist the teachers.

Teachers were also required to provide additional time for school works. They allot hours for consultation periods with students to ensure that the children really understood their lessons.

There are also consultation hours for parents if the teachers need to talk to them about academic performance and behavior.

“So when they have questions about your video, when they don’t understand something. In my experience, we also use the afternoon to call the parents when there are issues. That’s the challenge when there is no face-tofact, because back then, you’d be in school anytime,” he said.

Teachers have also had to use weekends for school work, usually making instructional videos. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Ronnie said they had weekends free for leisure activities and rest.

When it comes to the academic performance of students, Ronnie shares the same assessment as Joshua, the public school teacher, believing students do not answer their activities on their own.

“Well if you give them a task, they finish, if you give them a test, they answer but the integrity is questionable,” Ronnie said.

The first quarter of the school year officially ended on December 12 and learners had a holiday break until January 4. Despite birth pains, Undersecretary Diosdado San Antonio said the DepEd is satisfied with how the year is going.

“DepEd’s learning continuity plan is about making sure that the youngsters will be given the chance to learn the most essential learning competencies expected for their grade levels, and we feel that generally, we are able to do this,” he said.

“This was proven by the fact that we are able to open the classes last October 5. Ever since, we acknowledged that it is not perfect but we made sure that it is going to be flexible.”

Other reports, however, are not as encouraging. Participation of students in online learning has been dwindling, based on the reports of their members as of December, according to Teacher's Dignity Coalition national chairperson Benjo Basas. Even among students enrolled in modular classes, the engagement has been decreasing with students were submitting incomplete and sometimes unanswered activities. San Antonio said the DepEd is still validating this report.

In any case, there will be changes in how grades will be computed this year.

“One of the featured changes is that the assessment would be based on written outputs and performance tasks. The periodical test, a major element in the computation of grades, was omitted as it would be very difficult since there are no face-to-face classes,” DepEd Undersecretary Diosdado San Antonio said.

Senator Sherwin Gatchalian believes the assessment part is indispensable. “There are some people advocating that everyone should pass. We cannot do that also because if you allow a uniform passing, when that child reaches the next level, he will have a hard time because obviously he didn‘t learn.”

Grades are expected to be out a week or two after the last day of the quarter.

The use of self-learning modules would also be adjusted in the succeeding quarters of the school year, according to San Antonio. “There are various donations of tablets for learners. Those who have the gadgets would no longer be given printed modules. So, we will be making adjustments on the number of modules depending on what is going on,” he said.

After consulting DepEd regional directors, a memorandum of academic ease has also been issued to alleviate the stress of the learners.

“We agreed to release a circular or memo to ease the burden. We gave flexibility to teachers to minimize the activities that are expected of the learners. We discourage absolute deadlines because we would like to respect the learners’ paces and how fast they are able to complete the tasks,” San Antonio said, adding that continuous reconfigurations can be expected in the rest of the school year.

Ensuring that all students and teachers have access to the internet is also necessary, Gatchalian said. “We have to learn from this pandemic. This pandemic can happen again in the future, hopefully not. Or if not a pandemic maybe an earthquake, or maybe something else. What I want for our education system is no matter what happens, learning will continue. No matter what event —man-made, natural, pandemic, localized — learning must continue.”

He said he would lobby for universal access to laptops and the internet for all learners in the country. “We're trying to formulate a law wherein we will give every child, every learner a laptop and an access to the internet, much like access to electricity and access to water. It's now a basic necessity,” Gatchalian said.

But for the Alliance of Concerned Teachers, the problem is more fundamental.

“The primary issue is how much and how well the government is investing in education. Pre-pandemic and under distance learning, we are hounded with the same problems that bog down the uplift of education quality – lacking facilities, insufficient learning resources, overworked and underpaid workforce, and problematic curriculum,” said Raymond Basilio, ACT Secretary General, noting that the government allotted just P22 billion in funds for module reproduction this year, far from DepEd’s P50 billion estimate needed.

Still, the department is optimistic that experiences during this pandemic would help shape the future of education in the Philippines.

“Our immediate and long-term goal is to optimize the use of technology in making learning happen. We will harness technology, and based on our roadmap, we’re headed there,” San Antonio said. “If we see that these blended forms of learning are effective, we might not have full face-to-face classes every day, especially those in higher grades or the ‘very capable’ learners.”

Basilio does not share the rosy view. “We have long been in a bad learning crisis and now it is only getting worse.”

Meanwhile, the question of when classrooms will be filled with children again remains up in the air.

“I don’t think the DepEd can release a definite timeline. Everything will be dependent on the final decision of the President,” San Antonio said.

Education Secretary Leonor Briones has been presenting possible scenarios to the Inter-agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases about the reintroduction of physical classes. COVID-19 vaccines are projected to be available by March, but the new coronavirus variant complicates things.

“The most basic requirement for that is that it should be done in areas with low COVID-19 cases. This would also be granular, not for a whole city or province. Face-to-face classes may first be allowed in barangays or sitios,” San Antonio said.

For parents like Miguel Sobrepeña, the return of face-to-face classes, even if limited, could not come soon enough.

“If the attendance is limited and classes are not crowded, and if physical distancing would be ensured, I think it is OK. That program should push through,” he said.

“Because right now, I can’t let go teaching my children through modules to look for a job, you can’t do that.”

With editing by Raffy Jimenez