Filtered By: Topstories

News

Public works contracts under PNoy: Openness, savings, delays

By ROEL LANDINGIN, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

First of two parts

THE PROVINCE of Pampanga is one of the worst places to be in during the rainy season. Located at the bottom of a geological depression, it lies at the heart of Central Luzon’s drainage system where floodwaters from surrounding provinces converge before rushing out into Manila Bay. And within it lies another sinkhole, the town of Candaba, an old lakebed whose swamps and fields offer a temporary resting place for migratory birds on their way to and from North Asia.

No wonder Candaba’s mayor was furious when Public Works Secretary Rogelio Singson in late July 2010 cancelled a P78-million contract to repair the town’s dikes and riverbanks that help contain the waters of the Pampaga river.

At the time, Singson had barely warmed his seat at the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), having been appointed just less than a month before. Yet, he seemed already on his way to making his first enemy as DPWH chief, with the Candaba mayor warning that if the river swelled and the dikes collapsed, floodwaters would submerge not just Candaba but also the towns of Mexico, Sta. Ana, and San Fernando.

But the cancelled deal to rehabilitate Candaba’s embankments was just one among some 19 contracts for projects to rebuild infrastructure damaged by tropical cyclones Ondoy and Pepeng that the new secretary nullified after he found they were awarded with no public bidding.

In fact, within months of coming to power on June 30, 2010, the new administration either froze, modified, or cancelled scores of infrastructure projects, in accordance with President Benigno Simeon C. Aquino III’s anti-corruption campaign.

The contract cancellations may have discomfited Candaba’s mayor – and perhaps many of the townspeople themselves. But little harm was done in the end.

A PCIJ review of DPWH databases on awarded civil-works contracts and bidding results reveals that most of the suspended flood-control projects were eventually bidded out and implemented. We also found the DPWH got much lower prices for the contracts to carry out the civil-works projects, suggesting the delays were well worth it.

This is quite a surprise for a department long perceived as hopelessly corrupt and inefficient. The PCIJ itself had no expectations when it reviewed about 2,600 biddings conducted by the DPWH 18 months before, and 20 months after, the Aquino administration came to power on June 30, 2010, to see if there have been any palpable improvements in its procurement activities. Copies or summaries of the bidding results are posted on the DPWH website but PCIJ also asked for a copy of the database in spreadsheet format, which Singson readily granted. (Click here for the DPWH database)

A similar PCIJ request made to then DPWH Secretary Hermogenes Ebdane Jr. was not granted in early 2009.

Early gains

The PCIJ found that by most indications – and despite apparent resistance from some local officials – the much-maligned department seems to be finally paving its own daang matuwid (straight path), the battle cry of the Aquino administration.

For instance, the cost savings from awarding the suspended post-Ondoy and Pepeng rehabilitation projects through competitive tender could be signs of early gains from the new DPWH secretary’s campaign to curb graft in the department.

In Candaba, for example, the department tendered the contract to repair the dikes and riverbanks in January 2011, six months after it was cancelled. There were eight bidders, including Northern Builders, the original contractor, which offered the lowest bid of only P58.4 million, or a quarter less than the original contract price.

The difference amounts to some P24 million in real savings for the government; it gets the same structure built for much less. Northern Builders began construction in March 2011 and had completed 65.3 percent of the Candaba dike and riverbank works as of February this year.

Costs down 34%

Similarly, most of the 19 civil works contracts cancelled by Singson in July 2010 had been successfully bidded out in 2011, and many of the projects are already being built, according to data gathered by the PCIJ. At least three have been completed as of February 2012. New contract prices for 14 projects on which information is available show that the DPWH was able to bring down costs by an average of 34 percent compared to the original cost.

(Click here for the DPWH database on status of projects and the DPWH database on awarded contracts)

Singson has overhauled procurement and administrative systems and procedures at the DPWH in a bid to clean up the agency, which emerged as the most corrupt government institution in a 2009 survey by polling group Pulse Asia.

That year, the World Bank debarred five construction companies and two of their owners for rigging a series of biddings for bank-funded road projects. The Bank also released an internal report where it alleged that a cartel composed of private contractors and public works officials has been “institutionalized and has operated with impunity for at least a decade, possibly longer,” on account of the “systemic corruption and bid rigging” in the Philippine public works sector.

It added that evidence gathered by World Bank investigators suggested, “the cartel may enjoy support at the highest levels of the Government of the Philippines, including several officials of the DPWH and even reaching the husband of the President (Gloria Macapagal Arroyo) herself.”

Singson has reshuffled DPWH officials to prevent them “from being too familiar with contractors and suppliers, and to reduce the opportunities for colluding with them.” He also replaced other officials with serious eligibility deficiencies and pending complaints or cases.

Curbing collusion

The gains from the DPWH’s moves to toughen procurement policies are not confined to suspended projects that were subsequently put up for bidding. There are indications the department is making broader progress in the battle to curb widespread collusion that has artificially inflated the cost of public works projects in the past.

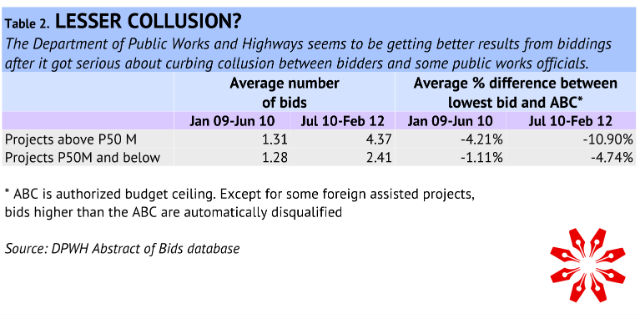

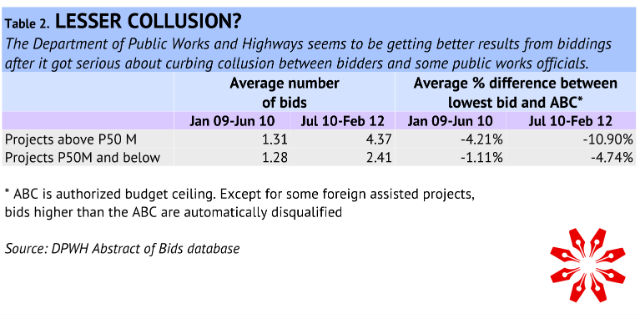

The PCIJ’s review reveals that the average number of bidders for large projects worth P50 million and more went up from 1.3 under the Arroyo administration to 4.4 under Aquino. For projects valued at less than P50 million, the number of bidders rose only a bit from 1.3 to 2.4. More bidders suggest more competition, which should result in lower price bids for DPWH projects.

This seems to be happening especially for big civil-works projects. The PCIJ compared the lowest price bids with the authorized budget ceiling (ABC) before and after the Aquino administration came in. The ABC is the DPWH’s estimate of the maximum cost of carrying out a civil-works project. It expects price bids should be below the ceiling.

We found that the average “price cut,” or the difference between the ABC and the lowest bid, for projects worth P50 million more than doubled to 10.9 percent under Aquino from only 4.2 percent under Arroyo, suggesting more competition perhaps because of the increase in average number of bidders.

For projects worth less than P50 million, the “price cut” more than quadrupled to 4.7 percent under Aquino from 1.1 percent under Arroyo.

Savings rate up

The DPWH claims much better results. It estimates that savings, or the difference between ABC and the awarded amount, on 106 contracts for civil works, goods and consultancies tendered by the central office and project management offices between July 2010 and November 2011 averaged 15 percent.

Savings on 5,091contracts tendered by regional offices and engineering districts averaged only 10 percent, according to its 2011 accomplishment report. Interestingly, post-Ondoy and Pepeng rehabilitation projects, which include contracts cancelled by Singson and tendered again in 2011, yielded the biggest savings of as much as 30 percent.

In peso terms, the savings amounted to P5.53 billion between July 2010 and November 2011, says DPWH, adding that it could reach P6 or P7 billion by the end of last year.

The department says that the budget allocation for the 5,000 or more projects between mid-2010 and end-2011 was around P60.5 billion. The aggregate ABC, however, was just P52.7 billion and the total contract award for those projects reached only P47.1 billion.

The DPWH considers these results an indication that the new administration’s moves to curb corruption and inefficiency are beginning to pay off. “Collusion in the bidding of public works projects is being addressed through transparency reforms and strict adherence to public bidding rules,” the department said in its 2011 accomplishment report.

Costly delays

Still, the DPWH’s estimated savings of P5.5 billion, commendable as it is, came after lengthy periods of administrative reviews that postponed the implementation of many projects. These inevitably delayed the completion of badly needed public works such as roads, bridges, classrooms, river dikes, irrigation canals, and others.

Economists say the delays in the availability of these crucial facilities have costs, too, and must be taken into account in determining if the DPWH’s savings are indeed significant in the bigger scheme of things.

The impact of the contract cancellations go beyond affected places such as Candaba. The revoked or delayed projects were widely blamed for the Philippine economy growing much more slowly than it should have last year. Infrastructure and other capital outlays fell below budget by 34 percent or P82.7 billion, more than half the total amount of underspending by government in 2011. Though business leaders welcomed the new administration’s anti-corruption drive, many are worried that it is coming at the expense of economic growth.

“The DPWH’s estimates of savings from better procurement must be assessed against the economic costs of delayed infrastructure,” says former Budget chief Benjamin Diokno, now a professor of public finance at the University of the Philippines. “For example, there is a cost when a classroom fails to be completed on time, and that is the value of education foregone by children who cannot be accommodated in schools because of a lack of classrooms.”

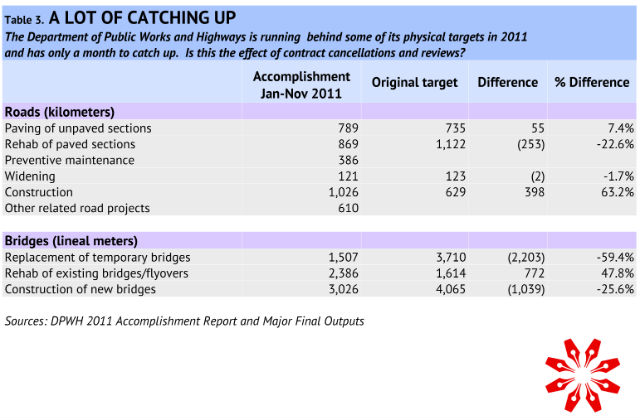

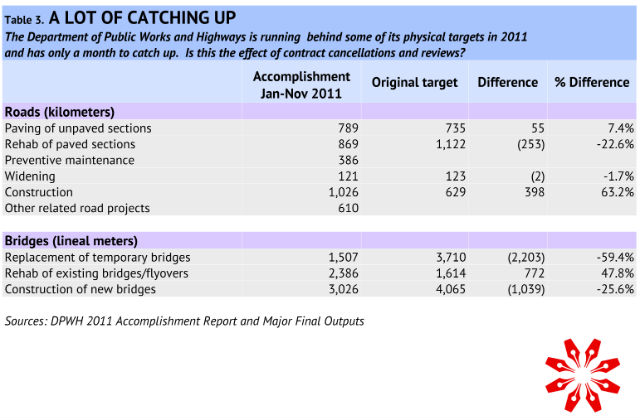

While estimating the costs of the delayed projects is difficult at this time, one can still have a sense of the magnitudes involved by comparing the DPWH accomplishments in the first 11 months of 2011 with its full-year targets. The department lists some 120 items as major final outcomes (MFO), a document that accompanies its annual budget, but reports accomplishments on only seven items related to the construction of roads and bridges.

Short of target

Based on the DPWH’s 2011 accomplishment report, the department appears to be short of its target to replace temporary bridges with permanent ones by 59.4 percent. That is equivalent 2,203 lineal meters of sturdier bridges, almost the same length at San Juanico Bridge. DPWH is also short of the target for building new bridges by 25.6 percent. That is equivalent to 1,039 lineal meters of new bridges that were not constructed. It is falling behind its target to rehabilitate paved roads by 22.6 percent, equivalent to 253 kilometers of better roads, almost the same as the distance between Manila and Baguio.

More than half of 833 school-building projects worth P754 million assigned to DPWH from the Department of Education in 2011 had not yet started as of November 2011. The DPWH hopes to catch up with its targets this year. It promised that all of the school-building projects began in 2010 and 2011 should be finished by the first quarter of 2012.

It managed to offset some of the shortfalls on its bridge building targets by building more new roads than planned. Of course, that is not much comfort to, say, a heavy-truck driver who must seek a longer route because a temporary or damaged bridge is not sturdy enough. Hopefully, as anti-corruption reforms take root in the department, honest tenders for public works projects will not come at the cost of their timely completion. – PCIJ, April 2012

Tags: publicworks, dpwh

More Videos

Most Popular