We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

By Howie Severino, GMA News

With design and additional research by Jessica Bartolome

November 12, 2018

He wanted to shoot birds and even larger animals. It wasn’t for pleasure or even for food. He wanted to kill for scientific knowledge.

He was an expert marksman, just one of the many talents of the great polymath.

But a gun he knew he could not possess in Dapitan, not when he was an exile, accused of fomenting rebellion. He revealed this small regret in a letter from Dapitan in 1893 to the eminent German scientist Dr. Adolph B. Meyer, director of the Dresden Museum in Germany:

“As I am only here as a deportee, I am not free to stroll everywhere as I please, nor can I use a shotgun, etc. Nevertheless, I shall do all that I can.”

With a lot of time on his hands, and no more political obligations, Rizal then was in the midst of a magnificent effort in Mindanao to get a deep sense of the “undiscovered treasures” of his homeland. He might easily have been the first Filipino to be engaged in biodiversity research, long before there was even a word for it.

On top of everything else he did in Dapitan – e.g., cure the sick, create a school, introduce irrigation, correspond with learned men, become a businessman, love Josephine Bracken, and literally win the lottery – he was combing the seashores and forests of his adopted hometown in search of specimens to send to some of the great museums of the world.

A doctor of medicine who had spent eight years in Europe studying with the leading specialists of his time, Rizal had a voraciously probing mind.

But in Dapitan, despite his fascination with creatures ranging from remora eels to wild boars, he could not qualify to be called a wildlife biologist or zoologist; his four years of collecting an assortment of fauna earned him the somewhat lesser status of “naturalist,” an enthusiast of nature of the highest order. He had no laboratories, university libraries, or intellectual community that would enable him to pursue advanced nature studies.

But even with the meager resources during his exile, Rizal managed to identify many of the species he collected just based on notes he had from his university days in Spain.

And there were some creatures he found that no one had ever identified before. Among Rizal’s less heralded achievements, four fauna species he collected would be named after him: the Draco rizali (flying lizard), the Rachophorus rizali (a tree frog), and two beetle species, the Spathomeles rizali (a.k.a. the “handsome fungus beetle”) and the Apogonia rizali (a flying beetle).

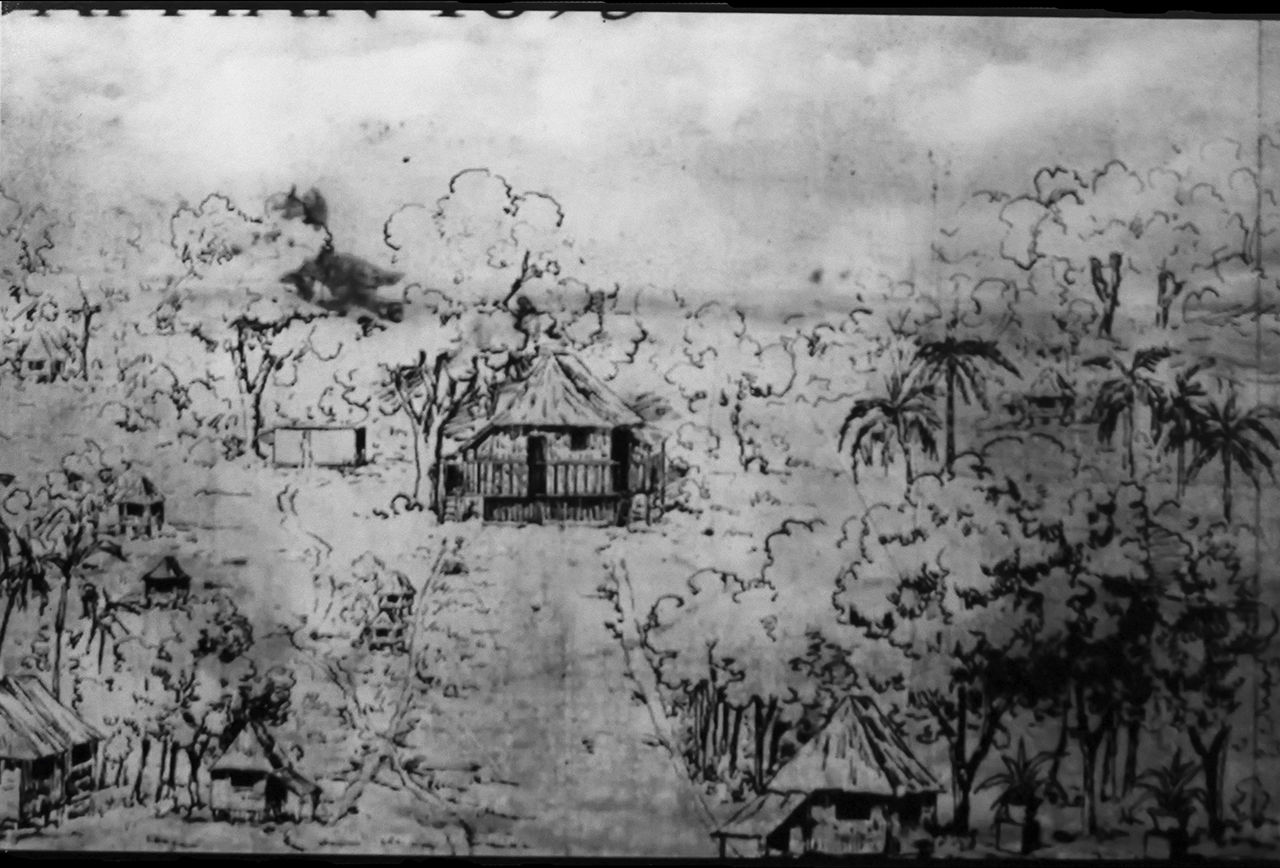

Despite having no laboratories, university libraries, or intellectual community that would enable him to pursue advanced nature studies, Rizal was able to make the best of what he had, as shown in this illustration. Museo ni Jose Rizal

I recently did internet searches on these exquisite creatures – the flying lizard is found only in the Philippines, and has broad, cape-like wings when spread; the tree frog has among the largest webbed feet I’ve seen on any frog species, the better to grip leaves and trees as they climb; and the so-called “handsome” beetle is really that, with striking orange spots on its shiny outer skin.

Rizal himself was not recorded as having said anything about these species, but I can imagine both the scientist and artist in him being delighted by their unique and beautiful features.

Maybe it was also that artist’s sensibility that drove him to spend an inordinate amount of time collecting visually striking butterflies and seashells. Or perhaps they were just relatively easy to gather. Rizal would write to friends that wildlife collecting had become his bonding activity with his dozen or so adolescent students.

Gathering was one thing, shipping to Europe was more complicated. Rizal sent hundreds of specimens to a German businessman acquaintance in Manila with a shop in Escolta, who then shipped them to Germany.

It was a rich menagerie of creatures: a wild boar’s head, a seahorse, a porcupine, scorpions, birds, snakes, turtles, fish, many of which needed to be preserved in alcohol, which was hard to find in Dapitan. One shipment of animals was on a boat that sank.

Rizal as a student. From Mga Sinulat Ni Jose Rizal, Mga Tala sa Paglalakbay, mga Alaala at Iba Pa (Unang tomo)

Rizal's sketch of himself, the original of which he sent to Blumetritt. From Jose Rizal: Correspondence with Blumentritt Volume II

THROUGH THIS ROUNDABOUT ROUTE, the animals were Rizal’s connection to some of the leading scientists of the time. Soon after he arrived in Dapitan, Rizal began a correspondence with Dr. Meyer, a scientist he had met in Europe through his close friend, the Austrian Philippinist Ferdinand Blumentritt.

Rizal offered to sell Meyer his collection of 200 or so seashells gathered on the shores of Dapitan. Rizal would eventually strike an ex-deal with Meyer, requesting books instead of money for the variety of Dapitan wildlife that would end up in European museums.

The books Rizal sought in exchange provide a window on what else occupied his mind in the prime of his life. Among those books: Greek classics by Sophocles and Aeschylus, the Russian writer Turgenev, and the “complete works of (Alexander) Gogol in German translation.”

Surviving to this day is Rizal’s list of the scientific names of the mollusks (seashells) that he sent to Meyer. His breadth of intellectual interests would elude other scholars; when Rizal’s letters were first published in Spanish translation, the historian Teodoro Kalaw who annotated the letters mistook the shells’ scientific names for butterfly species, an error that would be repeated in other accounts to the dismay of conchologists.

Rizal had an interest in seashells that long preceded his Dapitan exile. While studying medicine in Spain, he sat in on a class that tackled the taxonomy of mollusks, lessons that he would retain a decade later in a remote corner of western Mindanao.

Shells were featured in Rizal’s 1886 illustrated children’s story, “The Turtle and the Monkey,” which he drew while staying with Juan Luna in Paris. It was a comic-strip fable where the wise but earth-bound turtle planted sharp snail shells into a banana trunk as a form of booby trap for the greedy monkey. Those shells would be identified as susong papaitan from his native Luzon, similar to one species of shell from Dapitan that Rizal sent to Meyer.

Rizal had an interest in seashells that long preceded his Dapitan exile. While studying medicine in Spain, he sat in on a class that tackled the taxonomy of mollusks, lessons that he would retain a decade later in a remote corner of western Mindanao.

PERHAPS ENTERTAINING VISIONS of the national hero nimbly prowling Dapitan meadows with a net, writers have often associated those years more with butterfly collecting. In his towering 1961 biography “The First Filipino,” Leon Ma. Guerrero even entitled the Dapitan chapter A Commerce in Butterflies.

In truth, Rizal’s butterfly trade flopped. His prodigious knowledge apparently did not include best practices in how to ship sensitive creatures overseas. A prominent German expert on insects, Dr. K. M. Heller, told Rizal bluntly in a letter in 1895:

“I must inform you about the condition of the samples, which unfortunately leave much to be desired.”

One of Europe’s pre-eminent butterfly scientists, Napoleon Kheil, purportedly expressed a similar frustration with Rizal’s methods, as recounted by the biographer Guerrero:

“Kheil scolded him mercilessly. Had he no idea at all how to handle butterflies? One did not catch butterflies by hand but by nets; one did not pierce them with pins, but placed them carefully in envelopes, taking care not to spoil the wings!”

I was taken aback and then amused by this account of a “merciless scolding” of our revered national hero for ignorance.

But when I read an English translation of Kheil’s actual letter, the tone was certainly not a scolding, and there was nothing merciless about it. Kheil was in fact quite respectful throughout (“I admire you as a noble representative of colonial Spain.”), and his advice about collecting butterflies gentle, even deferential.

Neither was there mention that Rizal caught butterflies with his hands; Kheil just advised that he needed better nets and declared that he would be sending Rizal quality collecting nets and other supplies.

Guerrero was more than a tad over-exuberant in his account of this exchange, perhaps with the goal of humanizing an icon.

Instead, the reader is left astounded by what the correspondence shows of Rizal’s diligence in catching and sending delicate creatures halfway around the world. He just didn’t know how to do everything according to European scientific standards; but that wasn’t for wont of trying.

Rizal's illustration of a sting ray. Museo ni Jose Rizal

AS A RURAL DOCTOR, perhaps the only one for hundreds of kilometers around, Rizal had a professional interest in knowing which animals were harmful, particularly snakes. Rizal sent several snakes to Dr. Meyer in Dresden, who had the books and knowledge to identify them.

Rizal was particularly concerned about one green snake species, a sample of which was sent to Germany preserved in a bottle. To Rizal’s relief, he received the following reply from Meyer, more than four months later (all mail then, of course, traveled only by ship):

“I am rushing to tell you that the green snake is not poisonous, if not a completely harmless snake (Dendrelaphis) that lives in trees. There is a very dangerous green snake there, but it is relatively shorter, and has a thicker head and scales.”

I EMBARKED ON MY READING on Rizal as naturalist after visiting the National Museum of Natural History in Manila soon after it opened in mid 2018. It’s a glorious starting point for understanding the diversity of the Philippines’ natural environment. One disappointment though is the mere passing mention of Rizal and his pioneering contributions. As the museum evolves, I know they will see fit to add greater detail about the four tranquil years he spent studying the natural world in Dapitan and the species named after him.

Beyond his impact on the then-fledgling field of Philippine biodiversity, Rizal demonstrated in his Dapitan years what has been called a “practical nationalism.” Not everyone can write trail-blazing novels and envision a nation one hundred years hence, but Rizal in Dapitan showed that anyone can serve the common good in very practical ways: teaching local kids, improving local fishing and farming livelihoods, and most of all, learning all you can about your surroundings. He was the master class in how to be a useful member of a small community, and how to advance your knowledge even if you’re far away from centers of learning.

As a doctor, he needed to know which snakes were poisonous. But as a curious human being, he craved to learn about that marvelous flying lizard with cape-like wings, the one that would be named after him.

As someone who clearly imagined what his country could become, Rizal knew instinctively that in order to build a nation, one had to create knowledge not just of its history and politics, but its natural world.

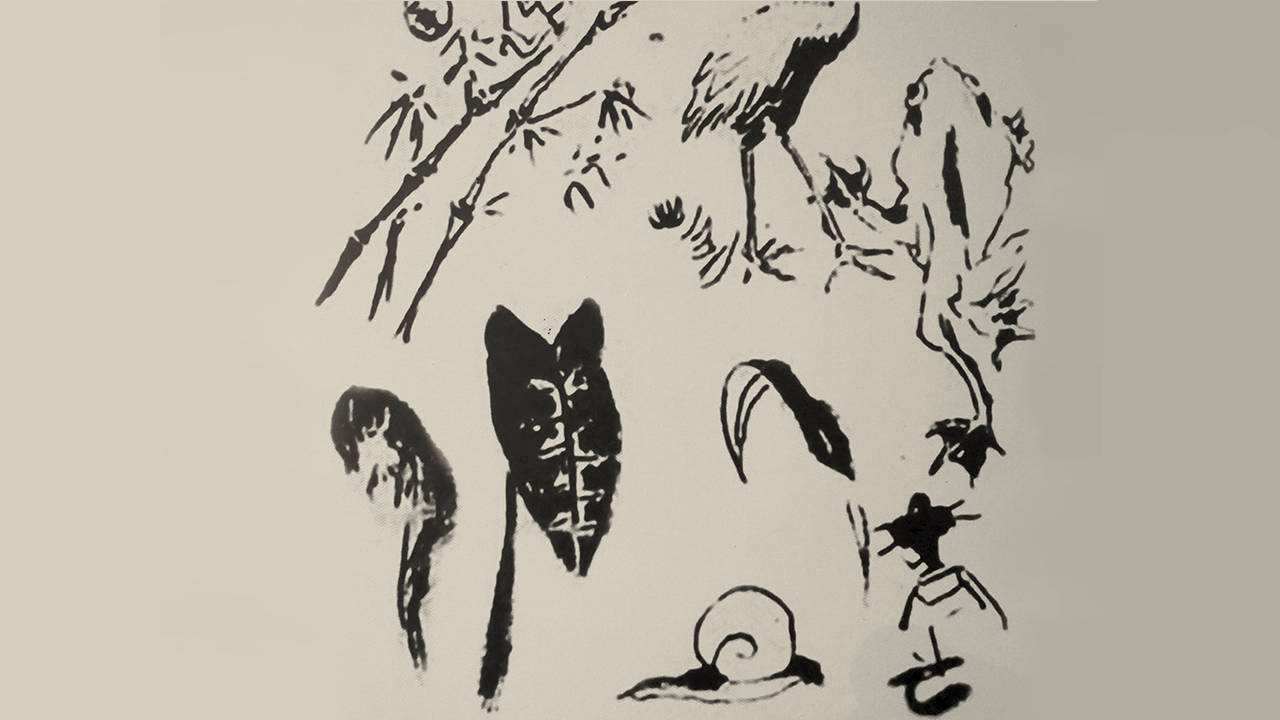

Seashells figured prominently in Rizal's studies, as well as his literature and artwork. Museo ni Jose Rizal

IT WAS ALSO IN DAPITAN, in his remarkable exchange of letters with the Jesuit priest Pablo Pastells, where he reconciled science and faith as clearly as anything else I’ve ever read:

“I believe in Revelation, but in that living revelation of Nature that surrounds us everywhere, in that mighty voice, eternal, incessant, incorruptible, clear, distinct, universal like the Being from which it emanates, in that revelation that speaks to us and penetrates into us from the time we are born until we die. What books can reveal to us better the goodness of God, His love, His providence, His eternity, His glory, His wisdom?”

While quenching his curiosity, Rizal’s explorations of nature were perhaps also his way of honoring creation.

Throughout most of his adult life, Rizal never stayed put in one place for very long. But when he finally did, against his will in Dapitan in the last four years of his life, he showed his kababayan how to live.

Share This Story