By SHAI LAGARDE

May 14, 2020

Every day around 4 p.m., I tweet the latest COVID-19 updates for GMA News. It started out as rumblings of an unknown novel coronavirus from Wuhan, China with a few hundred people infected. Reporters on the health beat would get together at the Department of Health press room for a quick briefing every other day.

Soon the cases piled up, the briefings became daily and extended into weekends. Three months and two name changes later, “COVID” and “ECQ” have become household terms as the pandemic continues to upend lives in ways previously unimagined.

While neighboring countries like South Korea and Vietnam got a grip on their crises without implementing drastic lockdown measures, our overwhelmed government still has their work cut out for it. Backlogs hamper case tracking and profiling, making it difficult to interpret (and act on) data in real time.

Equally challenging is the task of presenting new information with a clear messaging strategy. “PUI” and “PUM” are now “suspect” and “probable” respectively. People clamor for “mass testing” like in COVID-19 model countries. Protocols and guidelines — mask use, social distancing, ECQ, GCQ, MECQ — seem to vary not only from time to time, but from area to area

As COVID-19 hotspots Metro Manila, Laguna, and Cebu City transition from an enhanced community quarantine to its modified version this weekend, many things remain as confusing and uncertain as ever. Here are some of the questions I frequently get asked in my coverage on the COVID-19 beat.

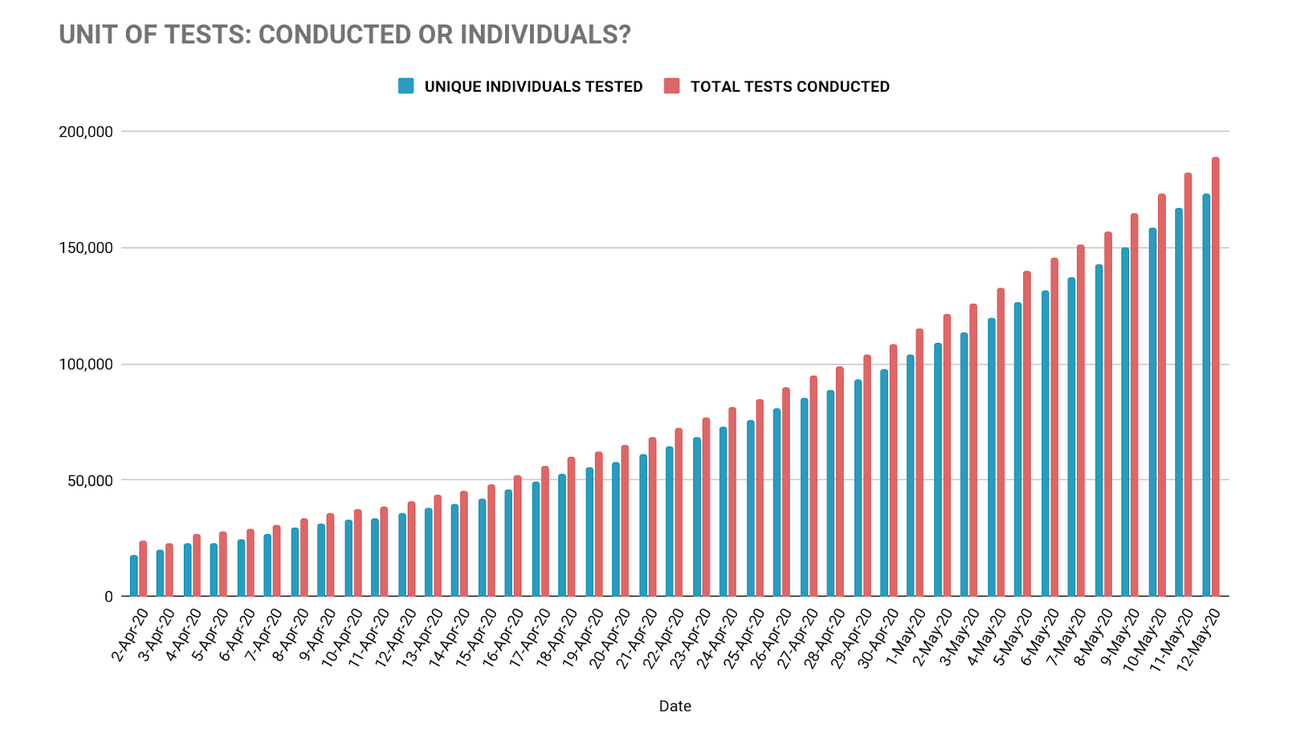

A COVID-19 patient needs repeat tests to check whether they are still infected with the virus or if they have recovered. DOH previously required two negative results before a patient could be discharged, but the guidelines have been changed to avoid overwhelming hospitals. It now only takes one negative result if the patient is asymptomatic. All tests that come back negative are added to the count of total conducted tests.

The difference between the two figures had previously led to some confusion. Before the DOH migrated into its current version, their COVID-19 tracker showed as few as 3,000 individuals tested by the end of March. A Twitter discussion ensued between GMA News journalist Atom Araullo who wanted to know why we aren’t testing more, and infectious diseases specialist Dr. Edsel Salvaña who disputed that we had actually conducted around 11,000 tests by then.

The tracker now shows nearly 189,000 total tests conducted, as of May 12.

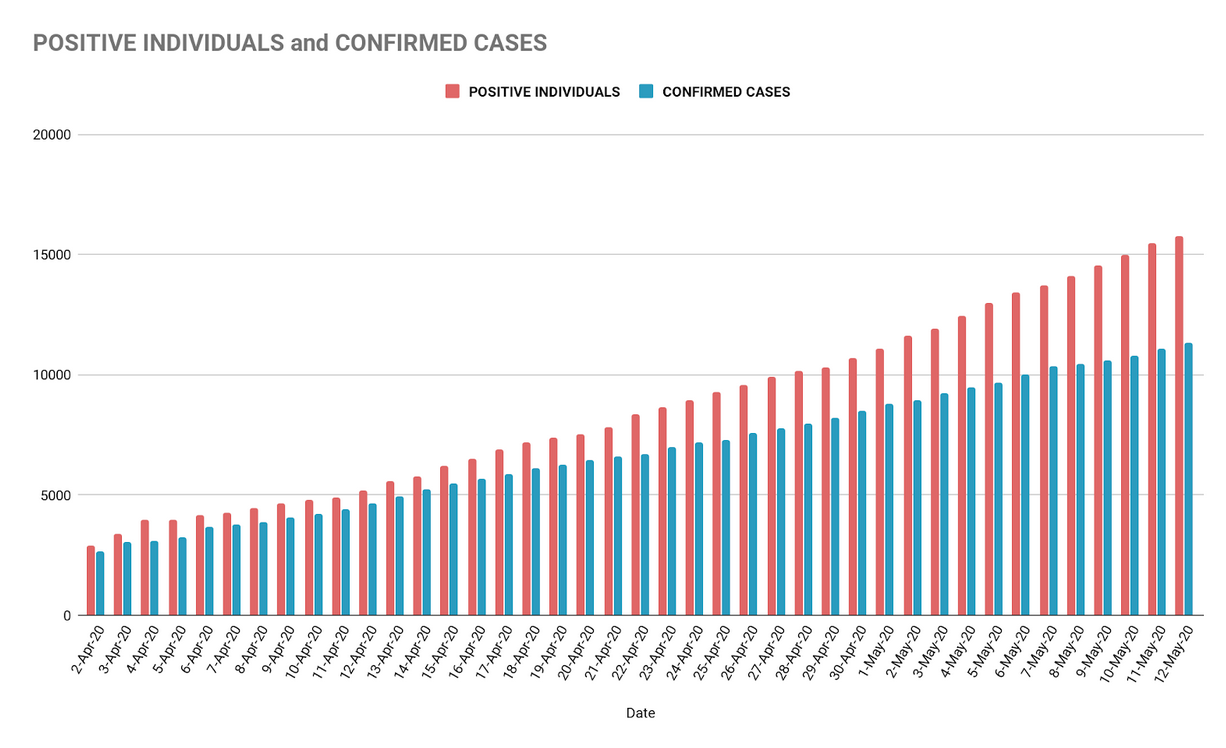

Confirmed cases are those that have been reported and verified by the Epidemiology Bureau and their local and regional Epidemiological Surveillance Units, before being included in the national list. Positive cases include results from laboratory tests that are still undergoing validation, so they don’t immediately get counted on the official case summary of the day.

The discrepancy between the two used to be significantly smaller. Recent dates show at least a week of delay—on May 12, there were 11,350 confirmed cases and 15,779 positive cases, presenting a backlog of 4,429 individuals.

There are now 28 licensed laboratories in the country, which could be one of the factors behind this backlog. Our current maximum testing capacity is at around 12,000 tests daily, taking into account the number of PCR machines available (one machine can process 44 tests in 8 hours), qualified personnel, and operating hours of each lab.

Minimum capacity is around 5,000 tests per day. Other factors may affect the actual testing output, such as lack of supplies (reagents or primers), machine maintenance, and scaling down of operations (as in the case of Research Institute for Tropical Medicine and the Philippine Lung Center, where lab personnel had to go on quarantine).

In total, only 173,302 individuals have been tested as of May 12. That’s 0.16% of our population.

DOH says their goal by May 30 is 30,000 tests per day. If they achieve this, it would allow us to see in real-time how intervention methods such as quarantine protocols are faring in the bigger picture.

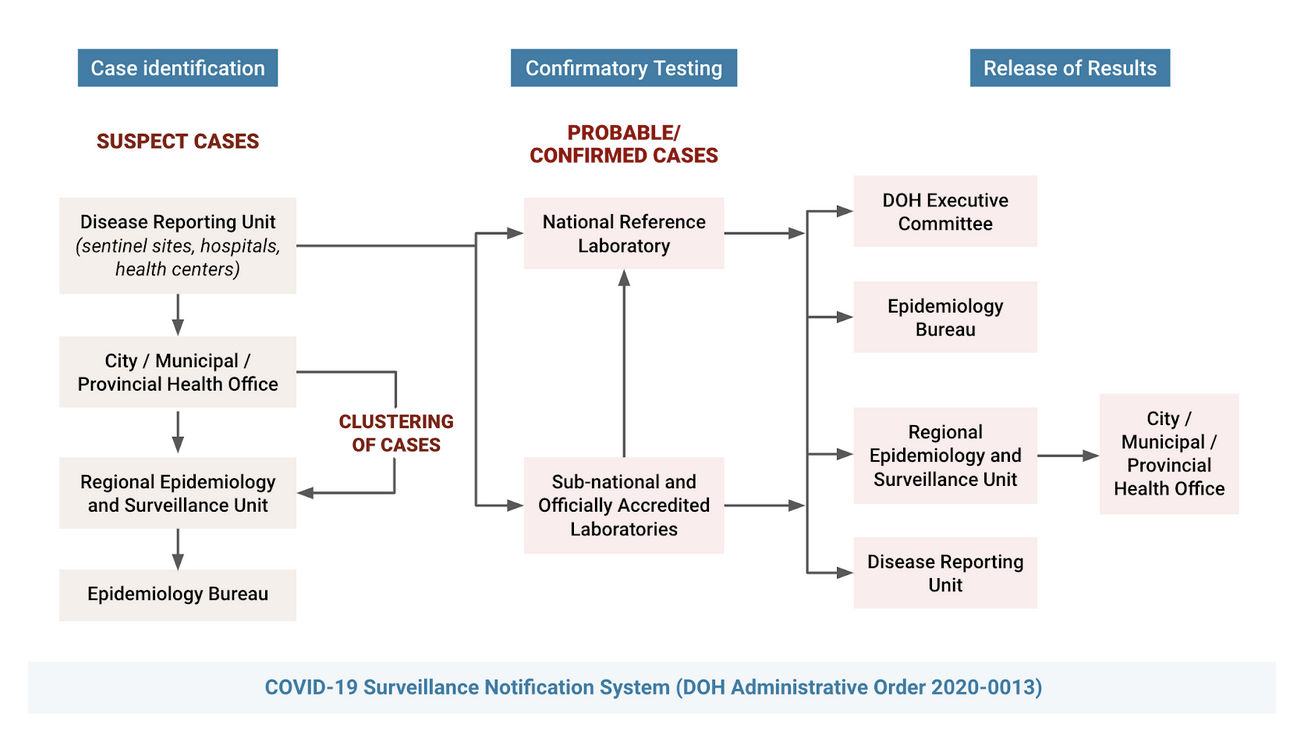

It’s not as simple as that. Here’s how cases are reported:

Let’s say a patient in a particular barangay becomes a suspected case. The hospital reports this case to the local government units (LGU), which then reports it to the Regional Epidemiology & Surveillance Unit (RESU) of the DOH. The RESU is required to submit a daily update to DOH’s Epidemiology Bureau (EB).

At the same time, the hospital sends the patient’s specimen for testing to the RITM or the nearest subnational lab, depending on zoning guidelines and other circumstances.

After two to three days, the test result will be released to DOH Central, the EB, the RESU, and the hospital that first reported the case. The RESU will then send this patient’s COVID-19 test result back to the LGU.

Assuming that this is the system currently being followed, it leaves a lot of room not only for delays, but also for inconsistencies and redundancies that would then need to be re-verified and even corrected.

This seems to be a reason behind the delays and encoding errors. The University of the Philippines Resilience Institute recently brought to the DOH’s attention some “alarming errors” in the data collecged by the agency. As early as March, however, these inconsistencies have been a constant source of confusion and frustration for those who closely monitor the data.

For example, there were days when over 300 cases would change age, gender, health facility, or city of residence without any advise from DOH; reporters and analysts would just notice it while we scrub the trackers for updates.

The Department has said that these have been resolved as of April 26, and that they make up for less than 1% of the overall data, so it doesn’t affect the interpretation of the whole. This may be true now, but at one point in March, these issues affecged over 40% of the overall data.

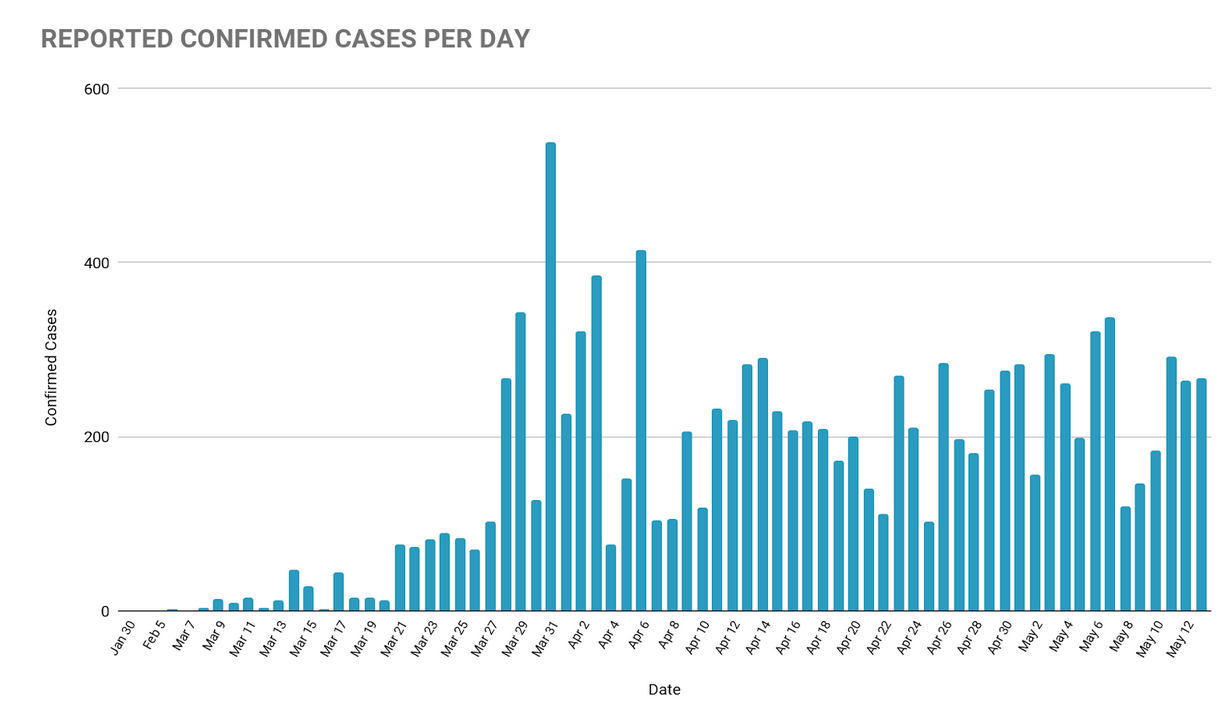

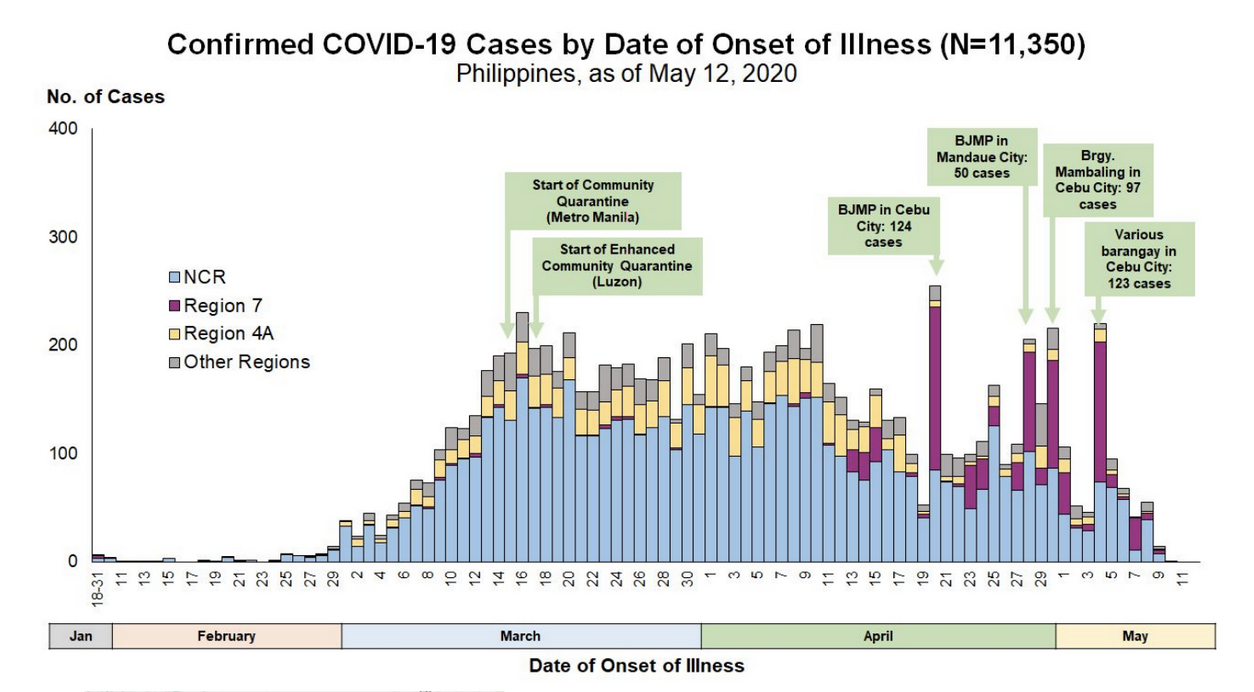

This is why we can’t solely rely on the graph of reported cases per day when assessing whether we are doing better or worse. A more reliable reference is the epidemiological curve, which is also available in DOH’s daily situationers. It shows the spread of the disease over time, irrespective of what goes on in the reporting stage.

For example, this graph shows the reported confirmed cases per day, regardless of when it was actually first reported:

The epi-curve below shows that new cases from April and May come in clusters, and that the overall rate of transmission seems to be slowing down:

This data could change depending on the date of onset reported for future cases, but it paints a clearer picture of the crisis.

The RT-PCR test, which is the gold standard for testing for COVID-19, requires a Biosafety Level 2 laboratory equipped to safely handle the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Before RITM was able to conduct tests independently, DOH had to send PUI samples to Australia and wait five to seven days for results to be sent back.

In February, the Philippines had one Biosafety Level 2 laboratory capable of handling 250 tests—not individuals—per day, servicing the entire country.

Meanwhile, the United States has been preparing against bioterrorism by building Level 3 labs as early as 2001. China has been constructing high-level biosafety laboratories since the SARS outbreak in 2003. After 40 people died in Vietnam from the bird flu in 2004, the government created a national infectious disease epidemic prevention system in 2006. South Korea’s MERS outbreak in 2015 had 186 confirmed cases and 38 deaths. Learning from this, they developed test kits and protocols as soon as the outbreak started in Wuhan. High-volume testing started as early as February.

Getting new laboratories online is not a simple task. A testing facility must conform to strict biosafety standards or it defeats the very purpose of preventing further infections.

The lab needs to have at least three rooms: one for virus inactivation, another for reagent preparation, and the PCR machine room, which must be vibration-free and dust-free and strictly limited to trained personnel.

The DOH requires five stages of validation: Stage 1 includes a 133-item self-assessment checklist; Stage 2 includes an on-site visit by the DOH, the RITM, and the World Health Organization (WHO). Stage 3 includes a three-day personnel training session at RITM; By Stages 4 and 5, RITM re-tests five samples tested by the lab to confirm if they arrive at the same results, after which they will be certified.

All 28 of our COVID-19 testing labs are at Biosafety Level 2. The countries mentioned above have several Biosafety Level 4 laboratories.

The goal of flattening the curve is to avoid infecting more people to prevent overwhelming our healthcare system. It aims to ensure that enough medical facilities, personnel, and supplies are ready should the need for them arise.

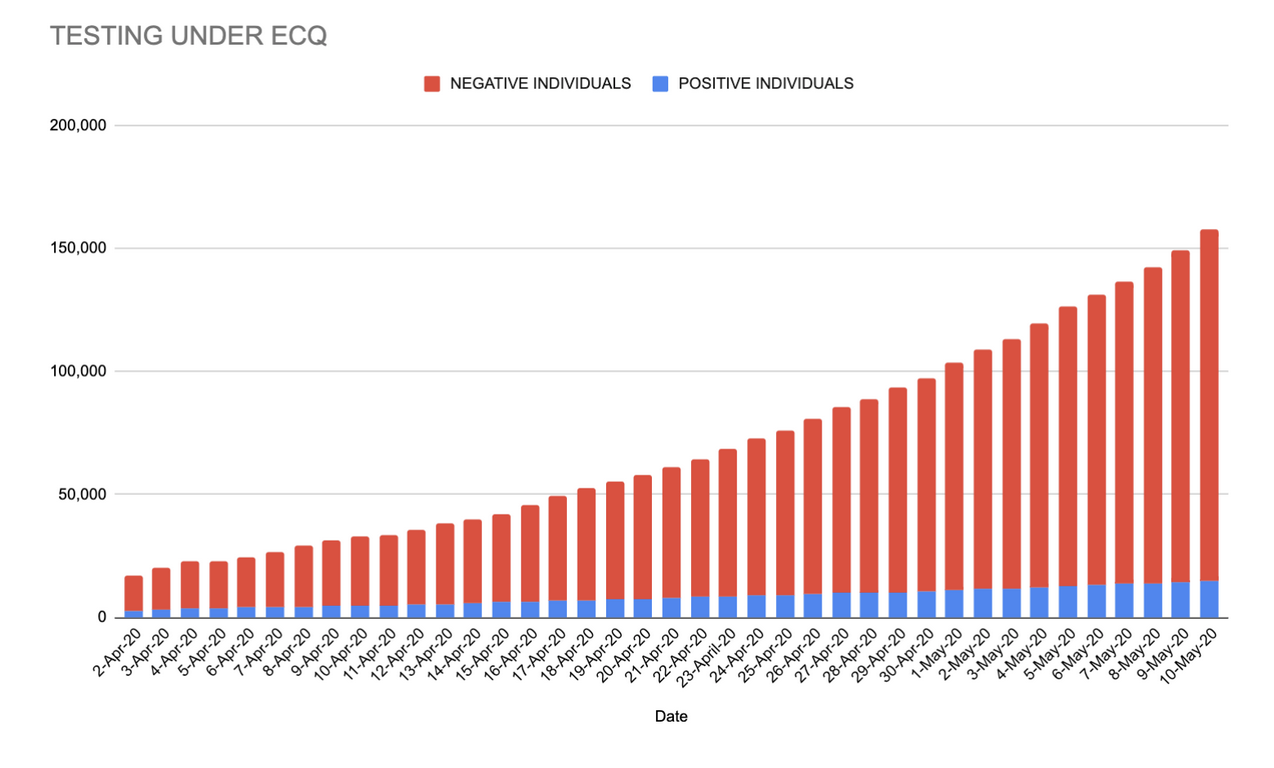

Upticks in the number of cases may have to do with larger testing capacity, and the way cases are reported from the local to the national level. While positive cases continue to increase as testing ramps up, so have negative cases.

This proportion of positive tests against the number of total tests conducted is called the positivity rate. From prioritizing only severe cases in the beginning, testing has expanded to those who have mild symptoms, and those who are asymptomatic but at risk.

The cumulative positivity rate was as high as 17.5% last April 4. As of May 12, it is down to 9.1%, which according to the DOH is in line with WHO’s target of 10% or lower.

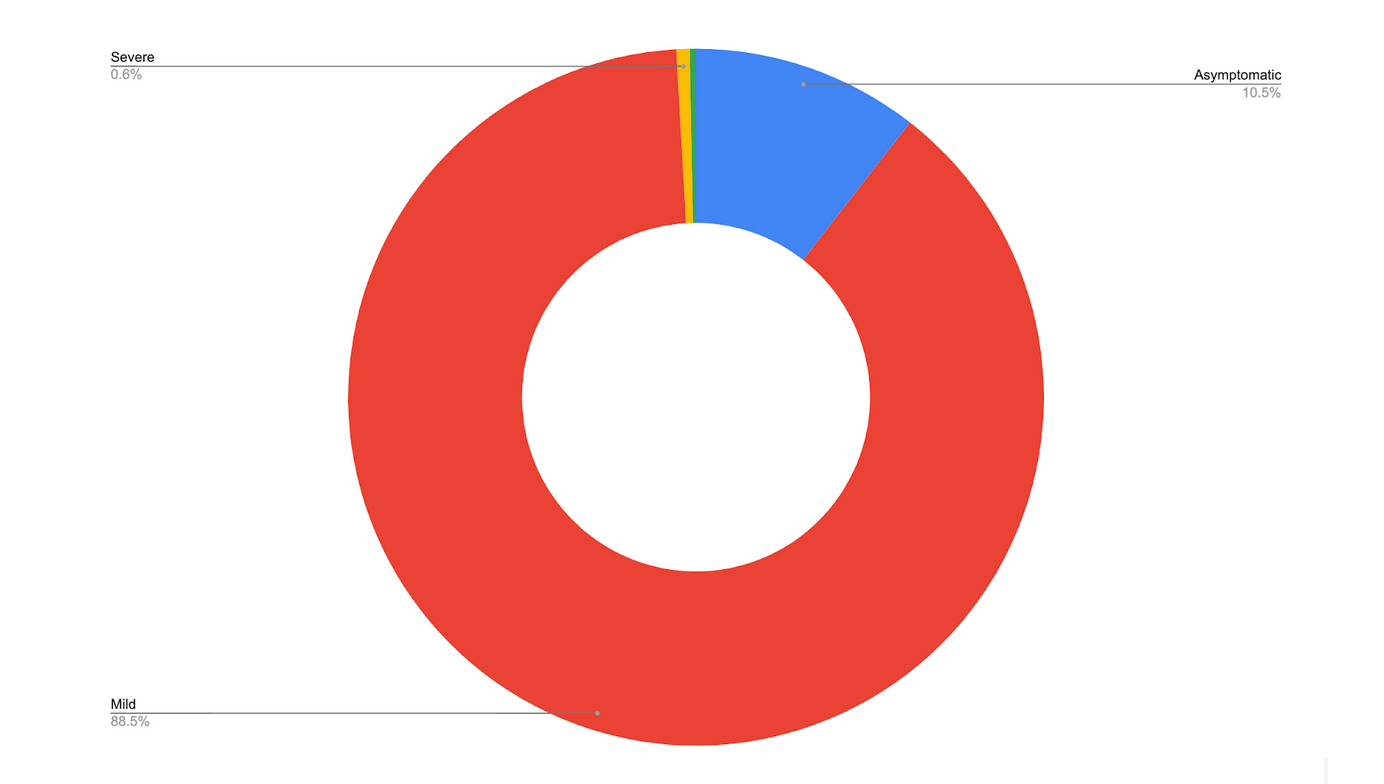

The chart below shows 8,493 positive cases (have not recovered nor died) as of May 12. 88.5% of them have only mild symptoms.

According to Dr. John Wong, an epidemiologist working with the sub-technical working group on data analytics of Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID), the Philippines has gone through its first wave of COVID-19, and we are currently on our second wave.

The first wave was through Chinese tourists PH1, PH2 and PH3, including the first death reported outside China (January 30-February 5).

We had no reported cases for nearly a month after that, until PH4 (travel history to Japan) and PH5 (frequent visitor of Muslim prayer hall in Greenhills) who brought about the second wave.

The goal is to prevent a third wave from occurring. By staying home and avoiding exposure risks, we have bought time so that our health care system won’t be overwhelmed, so that testing can be expanded further, so that a vaccine or cure might have more chances of being developed.

It’s not without its downsides and dire repercussions, but given the data, it’s hard to imagine how the Philippines could have prevented COVID-19 from spreading further without the ECQ.