By SHAI LAGARDE

June 2, 2020

The Department of Health reported 3,589 cases of COVID-19 from May 28 to June 1, as Metro Manila and other high-risk areas geared to shift from a Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine (MECQ) to a General Community Quarantine. The surge comes as the capital region prepares to relax many lockdown measures designed to help prevent the spread of the virus. Given the sharp increase, many are wondering: Are we actually ready to go into a GCQ?

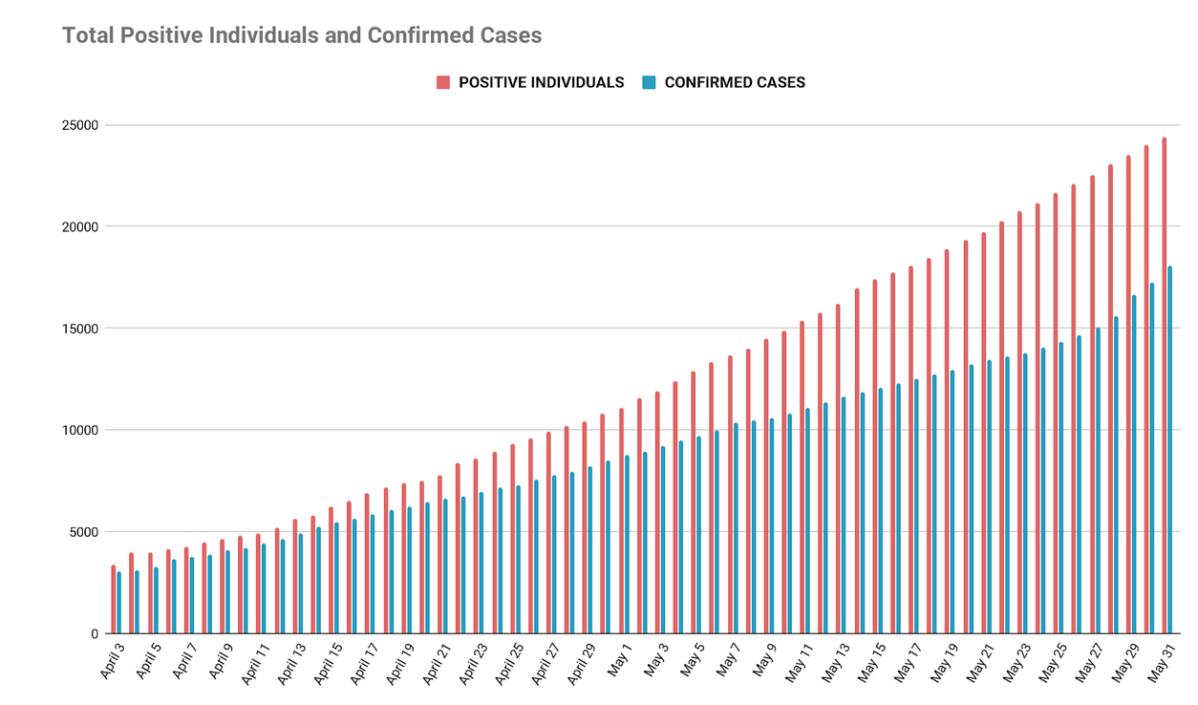

The surge in number comes as no surprise those who follow the reports by the DOH closely, given the large (and seemingly still growing) disparity between individuals who have tested positive for COVID-19 and the number of official cases confirmed daily by the government .

Everyday, laboratories accredited by the DOH return new positive results. However, these still need to be verified by the Epidemiology Bureau and the local and regional Epidemiological Surveillance Units of the DOH. This validation process leads to the discrepancy between positive cases and confirmed cases.

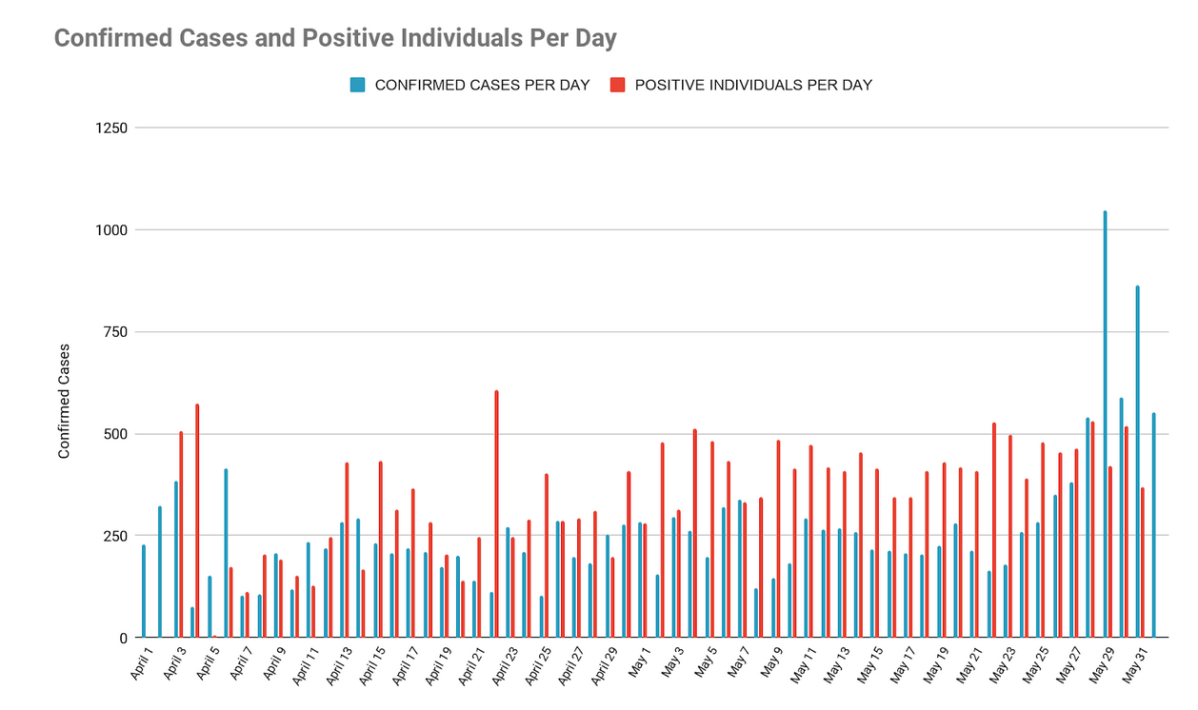

On May 29, the DOH announced that it would be changing the way it reported new confirmed cases: Fresh Cases, where test results are released to the patient within three days of being reported; and Late Cases, where test results are released to the patient in four or more days.

The DOH usually provides a daily case update at 4 p.m., but on the day of the announcement, they released their update past 9 p.m. This led to questions from people: Why now? Is it to soften the blow as the numbers being announced get bigger? Is it to justify the government’s decision to shift to GCQ?

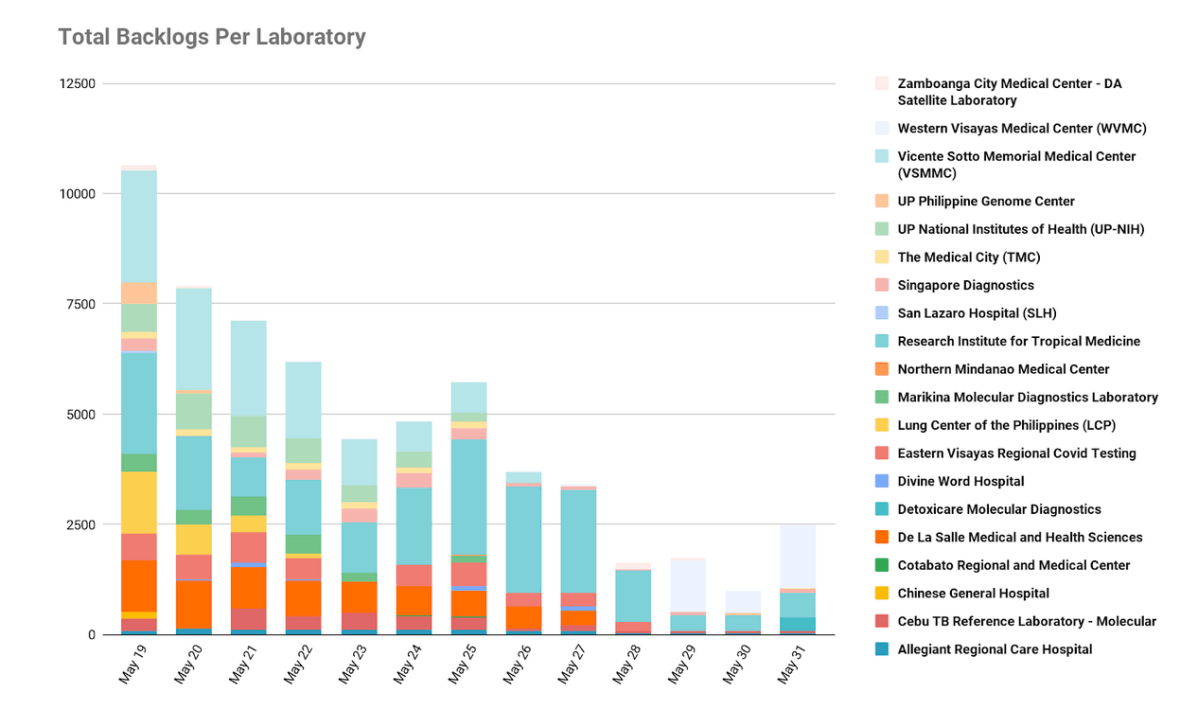

One big reason for the discrepancy are the backlogs from the laboratories. As the country ramped up its testing capacity, the tedious process of gathering data from different laboratories led to delays in reporting. The DOH defines a backlog as “the number of specimens received by the laboratory with no results released within the declared turnaround time (TAT).”

There were at least 10,000 backlogs recorded on May 19, spread across 16 of 33 laboratories that were operational at the time:

Under President Rodrigo Duterte’s directive, the DOH targeted to eliminate all backlogs by May 28. As of this writing, backlogs have crawled back to over 2,000 across seven laboratories.

The Philippines now has 49 licensed labs (38 using RT-PCR and 11 using GeneXpert). To streamline processes, data collection now goes through a fully-automated platform called COVIDKAYA.

Still, there remain many issues for laboratories. For example, the only laboratory in Bicol region suffered from downtime when Typhoon Ambo struck earlier this month. And while mega-swabbing centers have been set up (three in Metro Manila, one in Bulacan), laboratories can still be overwhelmed by the number of samples, as each machine can only accommodate a maximum of 44 samples at a time.

As a result, the Philippines has fared poorly in its target of running 30,000 tests per day by May 31.

Last month, Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque erroneously claimed that the Philippines has been meeting its targeted testing capacity per day. In reality, the country reached its April 30 target of 8,000 tests per day on May 10.

On May 31, only 8,268 samples were tested. The highest number of tests on record so far is 11,254 on May 14.

Roque later clarified that he was actually referring to maximum laboratory capacity.

On May 31, the DOH’s Epidemiology Bureau announced that they have cleared all the backlog cases for validation based on the completed lists submitted by 27 out of 42 laboratories, and are waiting for the rest of the labs to complete their submissions to be validated and included into the official count. “Starting June 1, no more late cases will be reported until the remaining operational laboratories submit their complete line lists,” their agency said in a press release.

Going forward, the DOH expects all laboratories to send daily accomplishment reports of all tests completed for the day, to be reported the following day. The status of submission of the daily reports would be made available to the public, to provide an accurate picture of the progress of cases as the country adjusts to the GCQ.

However, delays in laboratory results aren’t the only backlog that’s getting in the way of reporting cases real-time. Case validation (i.e. ensuring that all information about a patient is correct before officially confirming and reporting their laboratory test results) is a long and tedious process that’s affected by a few factors:

The health department has been addressing the second issue by hiring human resources en masse.

The number of positive individuals is almost always higher than the number of confirmed (reported) cases. Case validation roots out duplicates. For example, one individual would have two or more tests conducted while admitted so that their progress can be monitored.

With the total number of confirmed cases in the Philippines expected to breach 20,000 soon, there seems to be an effort from the health department to provide much-needed context and transparency, especially since they are dealing with data that is fraught with delays. All these delays mean that we are effectively still processing data from during the ECQ.

Amid questions from the public about fresh vs. late cases, the new reporting system of the DOH aims to give access to fresher data to paint a clearer picture of the situation.

“Our people deserve to know,” Health Secretary Francisco T. Duque III was quoted. And people want to know: Two and a half months later, are things better or worse?

Epidemiologists Dr. John Wong and Dr. Troy Gepte suggest that we look further than the number of confirmed cases. They point out three significant indicators that could gauge our response to the pandemic: (1) deaths, (2) critical care utilization rate, and (3) case doubling time.

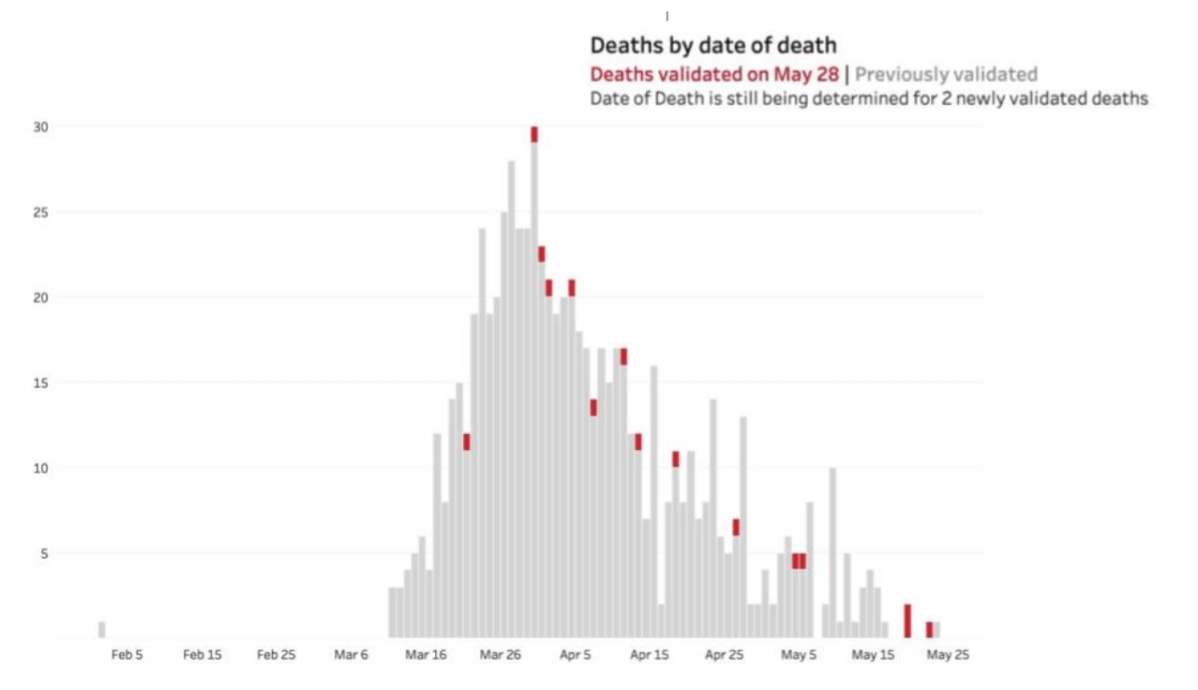

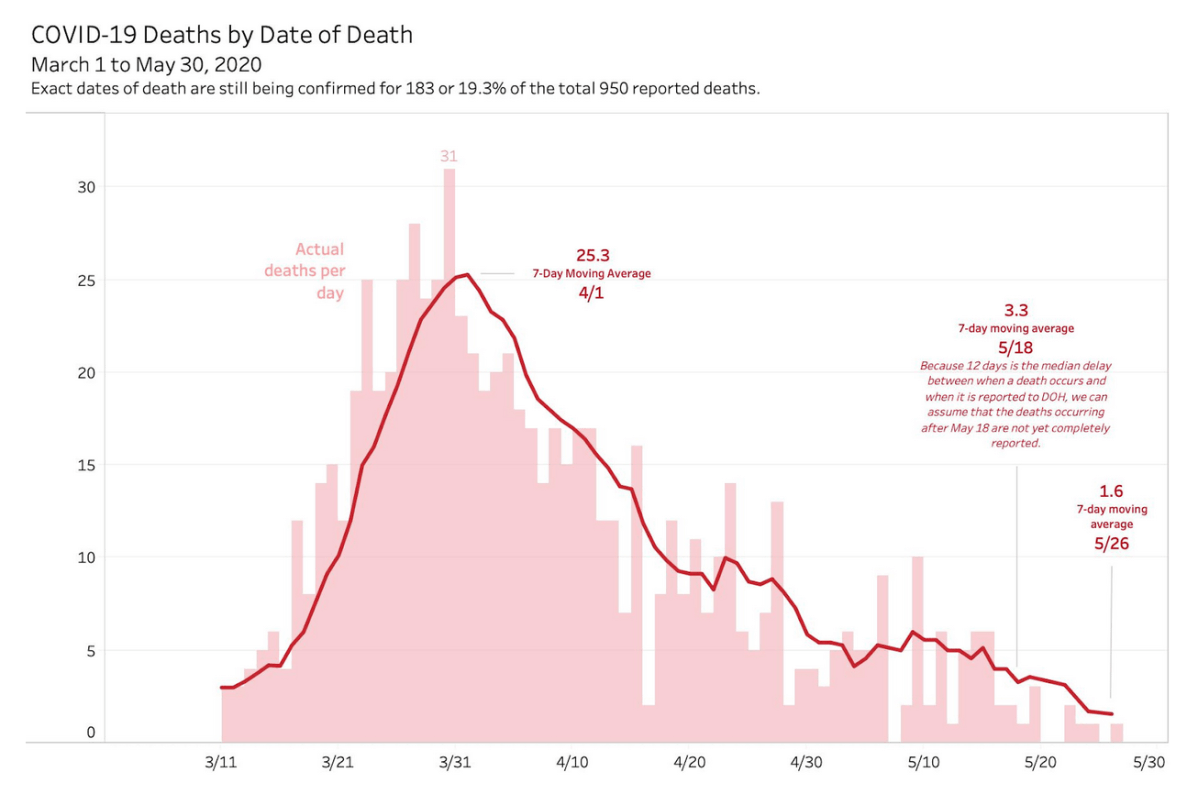

In her May 29 news conference, Health Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire reported 17 deaths, but noted that some of these cases had died in March and April.

Plotting the COVID-19 deaths reported on May 29, by date of death, rather than by the date they were reported, shows the following picture:

The data comes from various sources, which is why validation is crucial. This allows data to be presented more accurately and with the proper context.

The graphs above show that the peak of deaths happened toward the end of March, decreasing toward April. If the number of deaths continue a downward trend, Gepte explains, it would indicate the possibility that COVID-19 may already be peaking.

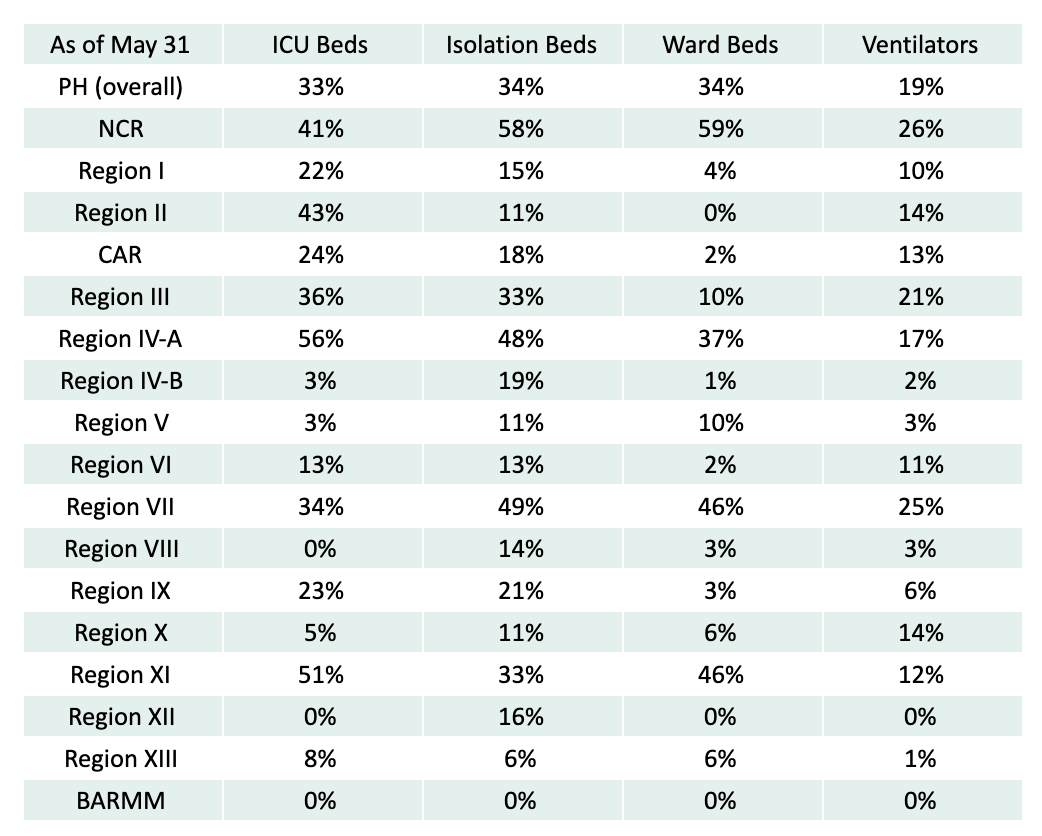

Simply put, critical care utilization rate refers to the capacity of our health system and facilities to respond to cases needing critical medical attention. It also indicates our capacity to handle severe cases and how much of our resources is still available for use.

Out of 1,311 available ICU beds in the Philippines, only 438 are occupied, putting our critical care utilization rate at 33.4%. Mechanical ventilator utilization rate is at 18.5% with only 370 of 2,005 total ventilators being used.

One of the goals of the lockdown is to "flatten the curve" to avoid overwhelming the health care system. Flattening the curve means the disease is spread more slowly over time, so not too many people are needing to be taken to hospitals at the same time. According to epidemiologists, the availability of hospital beds and ventilators is more likely a positive indicator.

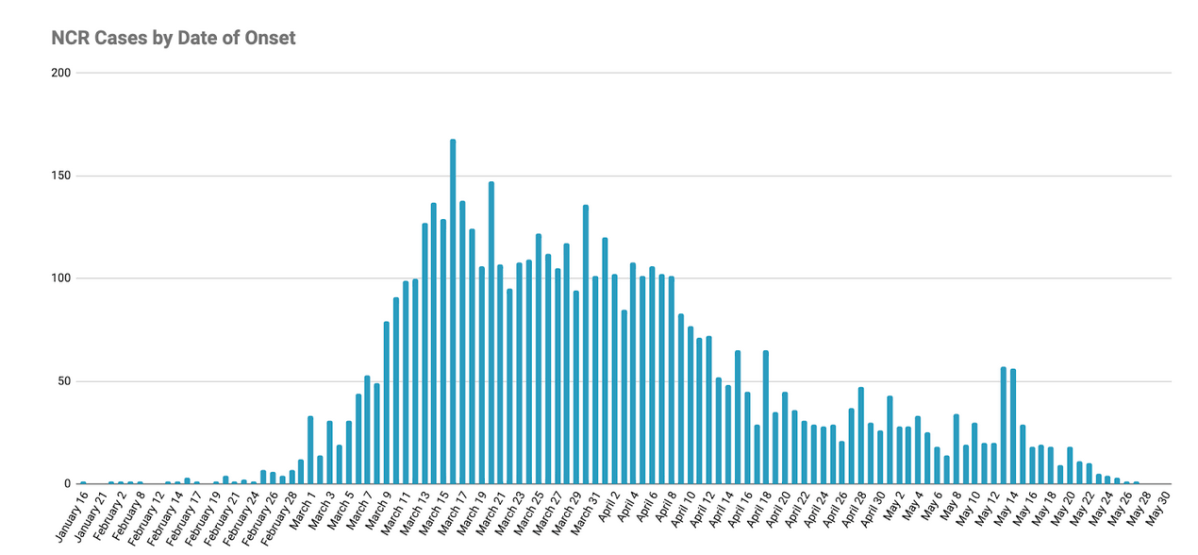

Case doubling time refers to the period it takes for cases to increase twofold. The longer the case doubling time, the better.

Per DOH, the case doubling time before the ECQ was two to three days. It was at four to five days in April, and is now at at 6.29 days for Metro Manila (the NCR accounts for almost two of every three confirmed COVID-19 cases in the country).

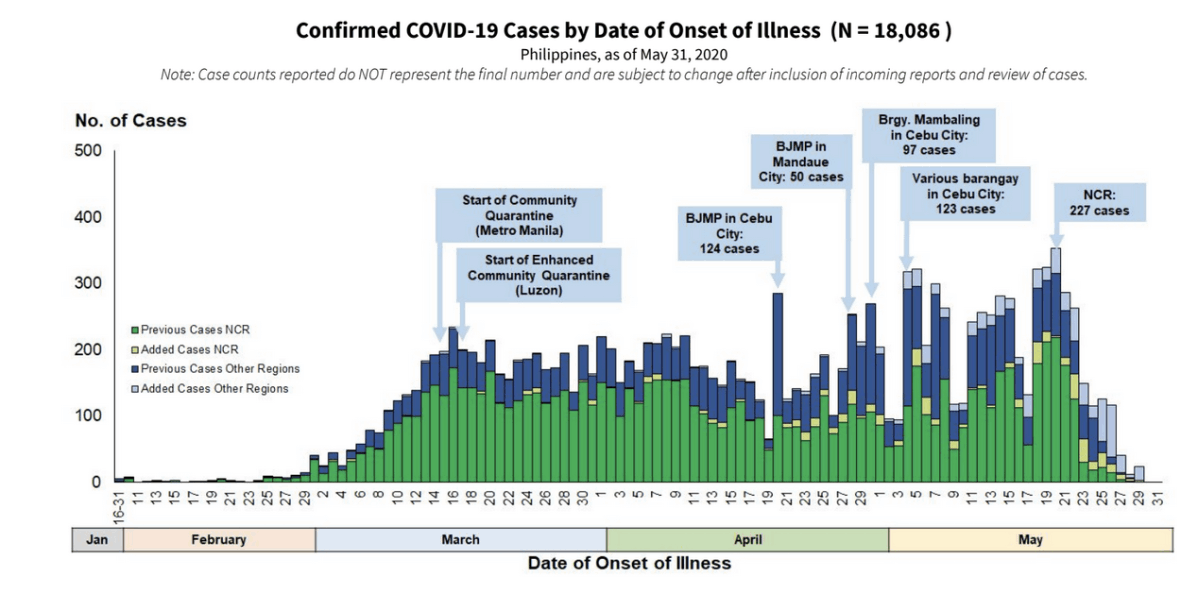

This can be visualized using the epi-curve, which is why it’s the more reliable way of looking at things. It’s based on the date of onset of illness rather than the date it was reported. Gepte stresses that these do not translate to an increase in local transmission at that very moment.

The new classification of “fresh” and “late” cases makes it easier to collect, report and interpret data.

The graph above shows that March and April saw a sustained increase in cases. This slowed down relatively by mid-April, when cases rose as more tests began to be conducted (as in the case of the two jails and various barangays in Cebu). The number of cases has started decreasing towards the end of May, despite the expanded testing.

The significant decrease seems promising. Still, the data is subject to change pending case validations. It has limitations since it is based on the data made available by DOH through its DataDrop, where some cases do not have complete information such as date of onset of illness.

More tests are being conducted now with the expanded testing criteria of patients and health workers who are:

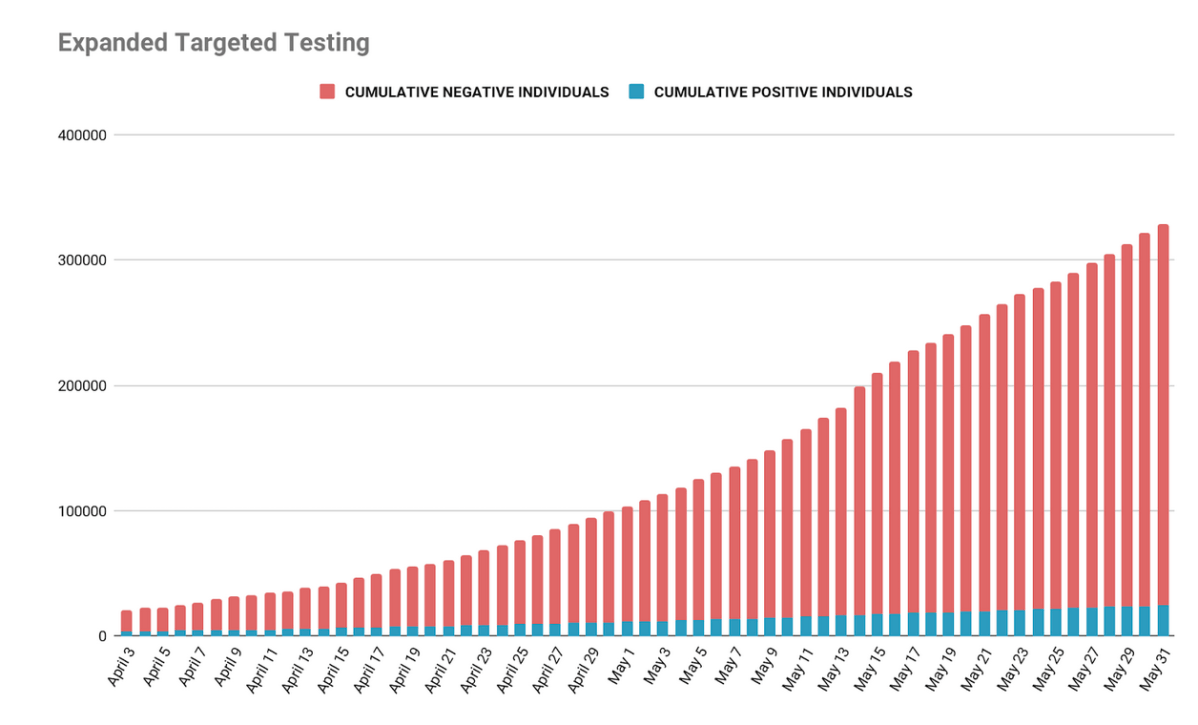

The graph below reflects the decreasing positivity rate (now at 7.4%) despite testing more people.

Still, because of the limited testing capacity, a mere 0.3% of the population has been tested. This means that there may be pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers who remain untested. While it is not the main way SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is transferred, the WHO has not ruled out the possibility of asymptomatic transmission.

If the data we have so far is to be trusted, then we have four things going for us: testing is increasing, deaths are decreasing, our health care system has adequate capacity, and cases are slowing down.

Whether we take this data with a grain of salt or a whole truckload, it’s important to note that the GCQ does not mean the minimum health standards have changed. It certainly doesn’t mean that we have controlled the rate of infection.

And despite the seemingly positive trends, there remain many questions as Metro Manila and other hotspots adjust to a GCQ. Implementation guidelines seem to differ across agencies, LGUs, and establishments.

People are anxious — suspicious at worst, ambivalent at best — that we are ready to go back out there. It doesn’t help that the government’s messaging often seems confused and inconsistent, with no clear-cut and specific protocols for how they plan to handle the inevitable rush of people on public places and transportation.

Perhaps we can also look to Japan’s success in curbing the spread of COVID-19 despite similar odds: They have a low testing rate (around 0.2%), the world’s oldest population, and a bustling public transportation system. They received nearly half a million visitors from China during the Lunar New Year, and dealt with a cruise ship outbreak in February.

Experts attribute it to their strict observance of physical distancing, regular wearing of masks, and good hygiene habits (frequent handwashing, disinfecting items, cough etiquette) even without strict lockdown measures. When the outbreak began, the Japanese have been careful to avoid the three Cs: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings. Perhaps there is something there, the government’s shortcomings notwithstanding.

We always knew the ECQ could only last for so long without irreversibly crippling the economy. And until the government stops placing this burden of responsibility on its citizens, we will have to keep protecting ourselves and our communities with the same survival measures that got us through 77 days of lockdown.