We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

The place where they extracted the treasure from my blood had been emptied by the pandemic.

I thought the procedure would be at the hyper-busy Philippine General Hospital. The actual venue turned out to be an academic building I had to search for at UP Manila’s desolate College of Medicine.

I walked down a hallway with desks stacked against the wall, mute testament to classes that were abruptly suspended.

Beyond the security guards at the entrance there was absolutely no one. I thought I was in the wrong place until I saw the room number I was looking for. Inside was a brightly lit classroom converted into a makeshift clinic with two young doctors.

In the weeks since I was hospitalized elsewhere for COVID-19, this simple space with a special machine was the destination of my dreams. Reaching it meant I had fully recovered and I could finally donate my plasma and be of value to someone else.

Before that momentous day, there was more than a month of suspense and anxiety.

Even while still recovering, I had already been receiving appeals for my plasma from doctors and loved ones of desperately ill patients. There were only a few hundred known COVID-19 survivors at that time (early April), not all of them willing or able to donate plasma. The official survivors then were outnumbered by the deaths in the Department of Health’s count, filling me with the dreaded uncertainty of which column I would eventually end up in. The appeals for my plasma felt like a vote of confidence in my survival and gave me further motivation to eat well and boost my immunity while in isolation so I could join the thin ranks of plasma donors.

Even after I was discharged from the hospital, the uncertainty about my fate was not over.

My symptoms were gone but I was still not considered recovered until I tested negative twice for the coronavirus. It was not until then that I could end my isolation and rejoin my family. Alas, after one negative result I was stunned to learn that I tested positive again for the virus several days after leaving the hospital.

Had I been reinfected? Or did the PCR test merely detect viral fragments from the original infection, as the latest science now indicates? New theories about this disease have unfolded nearly every day, sometimes upending conventional wisdom. Now even the vaunted immunity supposedly bestowed on recovered patients, the one major consolation from suffering from COVID-19, is in doubt.

Demoralized and lonely in my Quezon City quarantine, I decided to go home to Batangas where I could see my family without getting near them. But seeing them was enough. Perhaps the solitude in Quezon City far from loved ones was a source of stress that was affecting my ability to recover or at least rid myself of the virus once and for all.

The municipal health office of my small town sent a frontliner team to test me twice. After a few days, both PCR tests yielded negative results, making me officially a recovered COVID patient. On top of that, I was positive for antibodies on two rapid tests, further proof that I had in my blood the anti-virus warriors coveted in the battle against the disease.

I was now an automatic member of a growing club of COVID-19 survivors worldwide blessed with a special power.

I think that was the reason I was met by looks of appreciation by the PGH medical staff in that converted classroom. They explained that the plasma donation clinic was created in a classroom to be physically separate from the hospital which served as a COVID-19 referral center.

First though I had to be screened through an interview by a pathology resident and a blood test.

After waiting for an hour I learned I had qualified to donate my plasma.

They sat me in a permanently reclined chair and casually mentioned that there might be some “discomfort,” an occasional code word I’ve realized for “pain.” I proudly said, “Pagkatapos ng karanasan ko sa ospital, kayang-kaya ko yan!” (“After my experience in the hospital, that’s easy!”) – brave words to mask a sudden unease.

A needle was inserted in my arm, a tube was attached to the needle, and I was connected to an apheresis machine, the equipment that would separate the plasma from my blood and return the rest of the blood components – red cells, white cells and platelets – to the donor, me.

To divert my attention from any discomfort, I got into a long geeky conversation about Magellan’s voyage with the baby-faced director of the PGH blood bank, Dr. Mark Ang.

As the blood components were moving back into my veins from the machine, I did feel a little sting, but it was tolerable. I actually felt more giddy than anything else.

This was an important moment in my journey as a COVID-19 patient, a kind of graduation with honors. Not every patient survives, and not every survivor qualifies to donate plasma. I was able to do both.

But this personal achievement matters only because it can save the life of another person.

There are still many unknowns about COVID-19, but there’s a growing medical consensus about the life-giving value of plasma that came from a recovered patient with anti-bodies.

That’s why the doctors present during my donation called plasma “liquid gold.” With far fewer recovered patients than confirmed cases, the plasma from the two or three donors a day at PGH is treated like treasure. There is a great need for donors, which is why those who have already donated need to assure fellow survivors that it is a safe process that will make the donor happy that they gave.

I dare say what I gave is even more valuable than gold. You can buy gold; you cannot buy my plasma. I was told that a committee of doctors would decide on the recipient, surely a patient with my blood type and probably someone who may not survive without the infusion of plasma. It would be given to the patient for free.

As I sat there with that tingling feeling of blood moving out of and then back into my veins, I felt a sense of fulfillment from having lived up to a promise. Still very sick in the hospital, I vowed to myself and to the cosmos that if I survived I would pay it forward, doing things like donating my plasma, a crucial favor to an unknown stranger.

I had a recent conversation with Senator Sonny Angara, a fellow COVID-19 patient and plasma donor. He found out that plasma referrals and inquiries among doctors and hospitals were an informal process, and suggested that the Department of Health try to centralize the information and orchestrate the matching between patients and blood type availability. As infections and hospital admissions mount, this role will become more critical than ever.

After less than two hours, the procedure was over – the plasma was separated and the remaining blood components returned to my veins. The medical technicians handed me the small bag of the yellow plasma they just extracted from my body, so I could hold it like a mother with her newborn. After all, from my body just came this gleaming symbol of life.

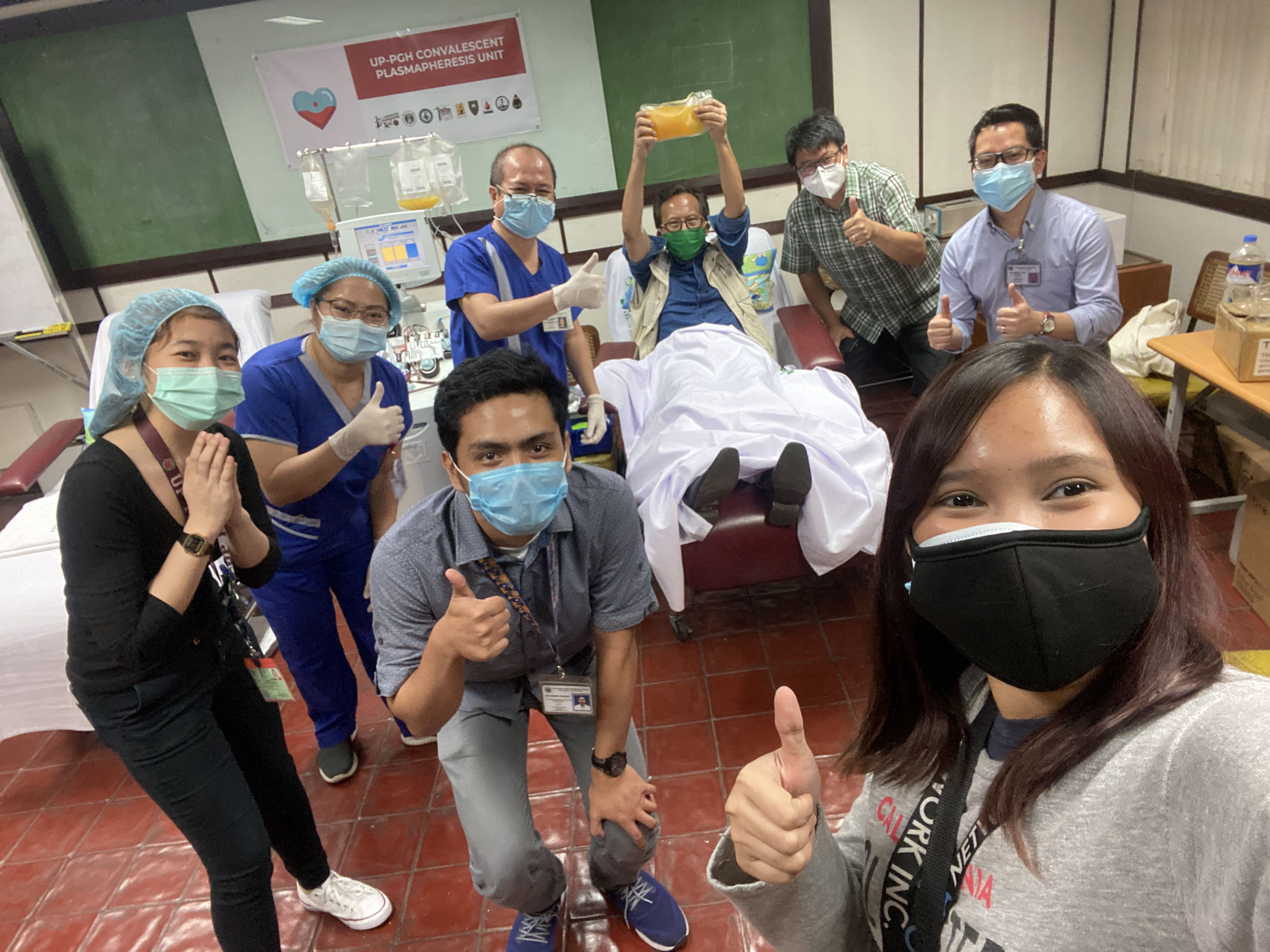

They had me pose with it as the medical staff gathered around me for photographs. I held it up like a trophy as they applauded and cheered for me. From being COVID-19 Patient 2828, I was now also PGH’s Plasma Donor 38.

Returning home that night, I reflected on the personal significance of that event. One of the worst things about being a patient is the feeling of being a burden. For all of its terrible attributes, COVID-19 enables a sublime epiphany: if one survives this disease, that feeling of being a burden can be replaced by a sense of wonder that you gave another patient out there a chance to live.

A version of this essay will be published in the "PGH Human Spirit Project" [working title], a legacy book filled with experiences of life in the COVID-19 era, to be published by the University of the Philippines Press this year.