By ANNA FELICIA BAJO

September 10, 2020

In the wee hours of August 10, neighbors heard noise from a rented apartment in Novaliches, Quezon City. When she checked, the landlady of the apartment discovered two dead bodies.

One of the men, a 71-year-old, had 15 wounds, two of which were described by those who performed an autopsy as like “slicing.” The injury on his head appeared to have been caused by a blunt object.

He had 12 incised wounds on his back. Both his eyes were black.

What caused his death was a “spike”, a weapon akin to a knitting needle, thrust into one side of his back to the other side. It hit his aorta but failed to go through because of its hook.

The attackers, the autopsy team would later conclude, meant to make him suffer.

That same day, progressive group Anakpawis broke the news about the murder of its chairperson and National Democratic Front of the Philippines peace consultant Randall “Ka Randy” Echanis and his neighbor. The group announced that the peasant leader was the man killed in gruesome fashion in Novaliches.

“What creatures can ever imaginably do that to a quiet, gentle, unassuming man of peace in his sunset years?” asked lawyer Edre Olalia, president of the National Union of People’s Lawyers.

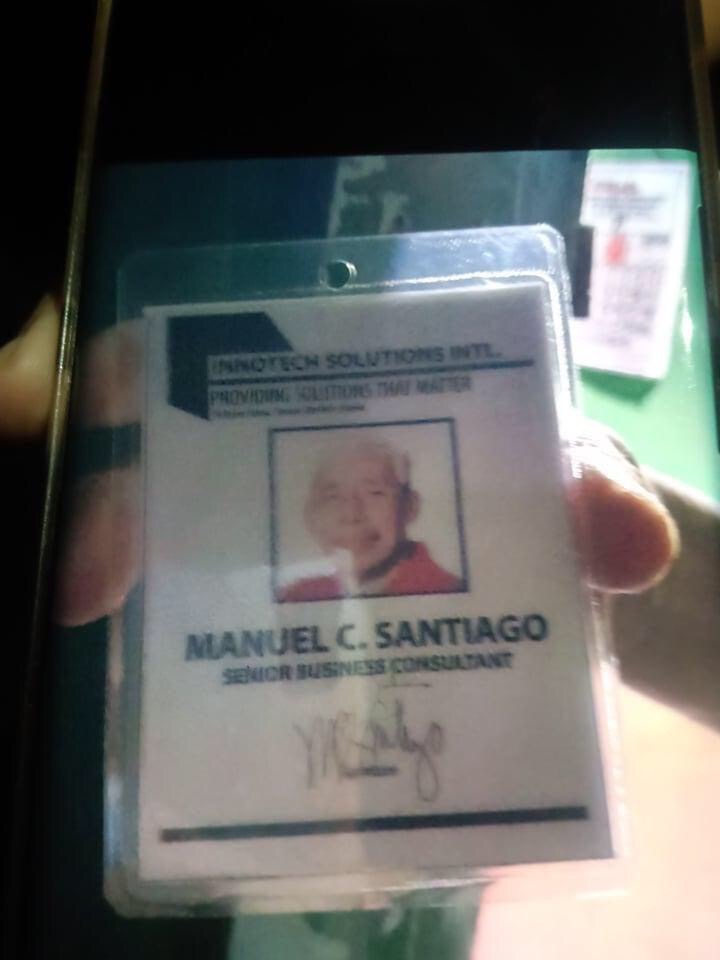

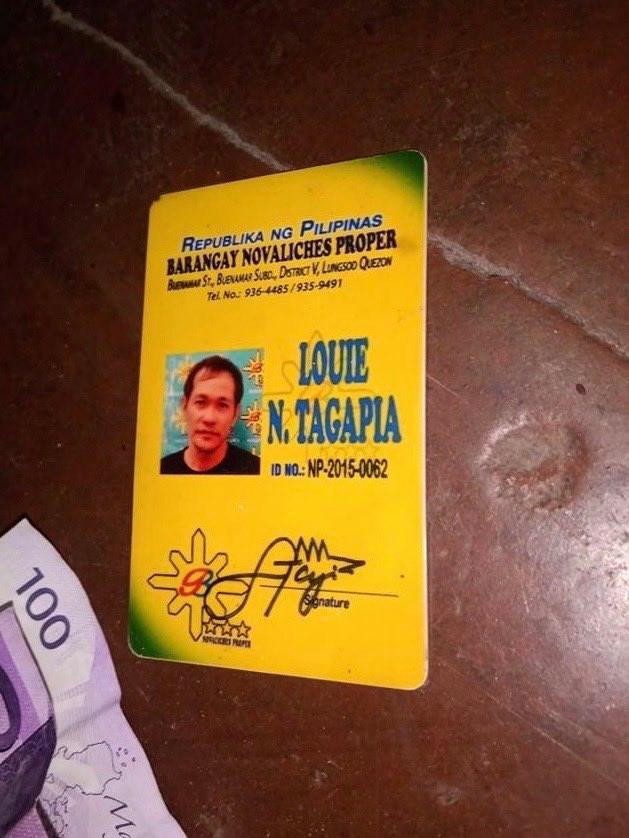

But the Quezon City Police District had another idea. In its initial investigation report, the QCPD identified the victims as one Manuel Santiago and a certain Louie Tagapia. Probers based the victims’ identities on ID cards found at the residence.

Investigators said they talked to the landlady of the apartment, who informed them that she knew the victims as Santiago and Tagapia. Investigators recovered a laptop, two flash drives and P400 at the crime scene.

For days, QCPD chief Police Brigadier General Ronnie Montejo stuck to the story that the NDFP peace consultant was not the man killed in the nighttime slays.

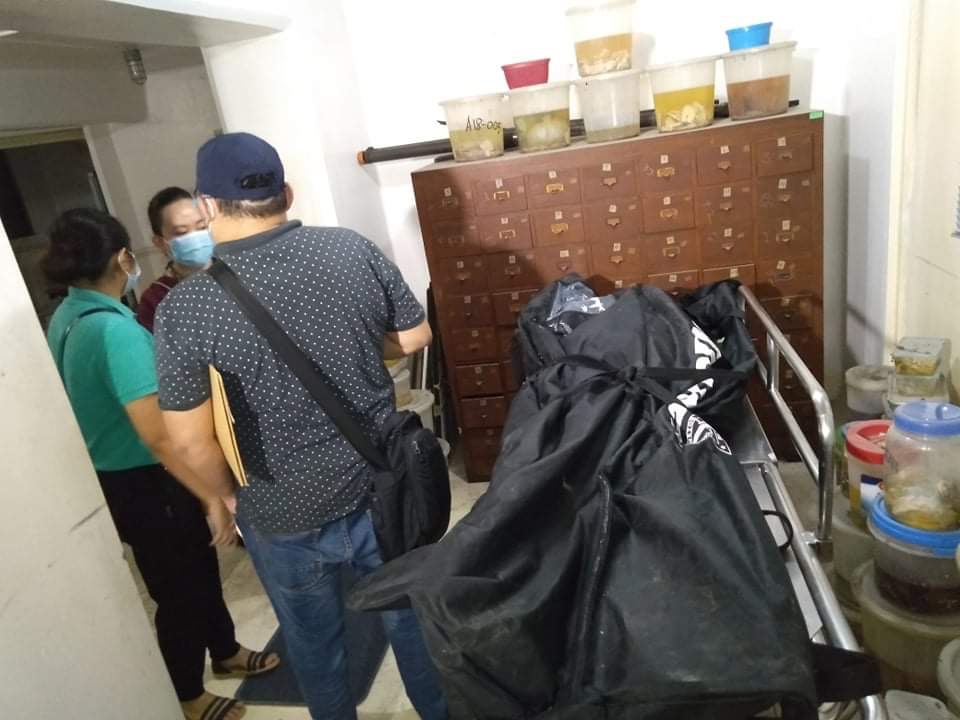

The remains were already at Pink Petals Funeral Services in La Loma when paralegal Paolo Colabres and lawyer Luz Perez arrived to claim the body.

On that rainy evening, Colabres had volunteered to be one of the representatives of Ka Randy’s wife, Linda, who had no quarantine pass so she was unable to go out to claim the body of her husband.

Linda gave Perez a special power of attorney to be able to claim the body. Colabres wore a paralegal shirt and an ID to properly identify himself to authorities.

The two representatives set up a video conference between Linda and the manager of the funeral parlor so the grieving wife could identify the body of Ka Randy.

“Pinakitaan siya ng picture, in-identify niya talaga na ‘yung isang picture ay si Ka Randy,” Colabres said.

(“She was shown a picture, she identified one of the pictures as Ka Randy.”)

The family of Ka Randy had even obtained a death certificate, allowing them to transfer the body to another funeral home.

But the police had another story. Based on their account, Colabres and Perez pretended to have been given approved by the QCPD Criminal Investigation and Detection Unit to claim the cadaver and bring it to the funeral parlor of their choice. The remains were taken to the St. Peter's Funeral Homes on Quezon Avenue.

After learning of the misrepresentation, operatives from La Loma police forcibly took the body at St. Peter and brought it back to Pink Petals. Perez allegedly evaded the cops, but Colabres was arrested without a warrant.

Colabres found himself charged with obstruction of justice for allegedly removing Ka Randy’s body from a funeral home without authority. He had to post bail of P36,000 to walk free, but only after seven days in jail.

He was detained at a cramped jail facility at Camp Karingal, where fellow inmates and even police officers were coughing and looked unwell. Upon his release by virtue of a court order on August 18, he immediately took a swab test, and was found positive for COVID-19.

But beyond what happened to him, Colabres lamented the plight of Ka Randy’s family. What stuck at his craw was the family having to pay the funeral home twice for the remains.

“Pinagbayad, kung ano ‘yung services ng funeral homes noong nai-release namin papuntang St. Peter, nabayaran na ‘yun in full,” Colabres said.

“Tapos nitong na-release na ako sa detention, nalaman ko nagbayad pa ulit para i-release doon sa Pink Petals noong for autopsy na sa College of Medicine ng PGH. Ako personally, hindi lang snatch-an, nanakawan 'yung pamilya ng punerarya.”

(“We paid for the services of the funeral home when we got the release for St. Peter’s, it was paid in full. When I was released from detention, I found out they had to pay Pink Petals again for release for the autopsy at the College of Medicine at PGH. Personally, it wasn’t just the body-snatching, the funeral home robbed the family.”)

The “body-snatching” compounded Linda’s grief. Her husband has been murdered, but she remained unable to mourn him as cops prohibited her from getting her spouse’s remains.

On August 12, two days after Ka Randy’s death, friends and supporters organized an ecumenical mass in front of the funeral parlor. It was an effort to get Linda as close as possible to her husband.

Authorities were loath to grant any small mercies to Ka Randy’s family, even for prayers for the dead. Invoking quarantine protocols, cops swooped down on Linda and company and stopped the mass.

“Barbaric, cruel and callous,” Olalia described the incident. “I was too kind and spoke too soon about expecting basic decency and respect for the dead and the bereaved family.”

The murder, as well as the police’s firm stance that Ka Randy was not among those killed mounted strong condemnation from militant groups and the Commission on Human Rights.

Later that day, the QCPD finally relented. It announced that a fingerprint test conducted by its crime laboratory confirmed that Santiago and Ka Randy were “one and the same person.”

Montejo, the QCPD chief, issued an apology to the victim’s loved ones. He sought their understanding, saying the police were just following the protocols for identifying a cadaver.

On the evening of August 12, Linda was finally in possession of the body of her husband.

Former Anakpawis partylist Representative Ariel Casilao could not understand the stonewalling by the police, noting how the family and the organization had always intended to cooperate with the probe.

What it did, Casilao said, was to deny Ka Randy’s loved ones of the opportunity to mourn him after his untimely death.

“Usually naman tradisyon at kultura ng mga Pilipino na kapag may namatay, ibuburol, paglalamayan, ililibing o ike-cremate,” Casilao said.

“Pero sa case ni Ka Randy at sa pamilya Echanis, pamilyang Anakpawis, they denied us for that instance eh na makapagdalamhati kami, makapagbigay kami ng tribute kay Ka Randy, sa loob ng tatlong araw na inagaw nila, pinahirapan nila 'yung pamilya.”

(“Usually in Filipino tradition, when someone dies, we’d have a wake, before the burial or cremation. But in Ka Randy’s case, the Echanis family, the Anakpawis family, they denied us the opportunity to condole, to give tribute, they snatched that from us for three days. They made his family suffer.”)

The QCPD chief promised that all angles would be investigated, including robbery and personal grudge, in the slay of Ka Randy and Tagapia. They identified the younger man as an alleged gang member.

Police Major Elmer Monsalve, the head of the QCPD criminal investigation and detection unit, floated the possibility of Tagapia as the main target of the suspects.

In a press briefing, he said Ka Randy had stab wounds while Tagapia had wounds in his head and his hands were tied when his body was found. Authorities are yet to determine the relationship between Ka Randy and Tagapia.

Anakpawis has little faith in the latest pronouncements by police. The group believes the robbery angle merely part of the “script” by the cops.

“If they fail to project that the case of Ka Randy is a robbery gone wrong, they will be forced to look for another alibi,” Casilao said. “We cannot trust alone the flimsy investigation and the manner the PNP handled the first three days.”

Instead, Casilao believes that Ka Randy’s death was politically-motivated, and called for an impartial probe led by the human rights commission.

Prior to his death, Ka Randy had already been receiving threats. According to Casilao, this started when peace talks between the national government and communist groups.

The former lawmaker claimed that since then, the government has been running after NDFP consultants, resulting in some “illegal arrests.” This prompted Echanis to limit his public engagements and distance himself even from his own family.

“Hindi na pumunta ng opisina tapos he decided also to distance from the family para hindi rin madamay,” Casilao said.

(“He didn’t go to the office anymore and he decided to distance himself from his family so they wouldn’t get hurt.”)

Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra has tasked the police to explain why they transferred the cadaver from one funeral parlor to another. Guevarra also ordered the AO 35 task force — the inter-agency committee it chairs to probe extra-legal killings, enforced disappearances, torture, and other human rights violations — to form a special investigating team to look into the incident.

The Commission on Human Rights has since launched its own probe into the death of Ka Randy, which also intended to look at how cops handled the case.

Colabres, the paralegal, also could not believe anyone would hold a grudge against Ka Randy, with whom he had worked closely before. Of the many killings he has had to probe, he described Ka Randy’s death as “the most hideous.”

Ka Randy, Colabres said, had no enemies on a personal level, but had plenty on a political level.

“Itong peace process nga ang hinahawakan niya kasi ‘yung socio-economic reforms eh, agrarian reform...” Colabres said.

(“He handled the peace process for the socio-economic reforms, agrarian reform…”)

Colabres describes Ka Randy as cheerful and dedicated to his mission to help farmers and fisherfolk.

He had known the peasant leader since 2007 when Colabres volunteered for an event for the rural poor sponsored by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines.

Colabres remembers how, despite his old age, Ka Randy continued to help the poor.

“‘Pag may mga relief, talagang mas matibay pa siya sa akin eh. Noong time na nakilala ko siya, mga 60 na siya ako mga 30s lang so matibay talaga si Ka Randy,” Colabres said.

(“Whenever there is a relief operation, he’d even be tougher than me. When I met him, he was in his 60s while I was in my 30s, so he was really tough.”)

Their work extended from Cagayan province in the north to Zamboanga in the south. As part of his volunteer work for the poor,Ka Randy would even use his personal money to try to provide for basic needs.

“Kung ano ‘yung mayroon, ‘yun ‘yung kakainin, ‘pag wala, walang kakainin. Parang isang kahig, isang tuka rin kami sa ganoong sitwasyon ‘pag nasa community,” Colabres said.

(“Whatever we had, that’s what we’d eat, if we didn’t have anything, we wouldn’t eat. It was hand-to-mouth, our situation whenever we’d be in the community.”)

In a series of social media posts, writer Fides Lim narrated how Ka Randy and the former Linda Lacaba met during the First Quarter Storm in 1970. They were together, however, only for a moment.

Ka Randy was arrested and jailed as a political prisoner until the fall of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986. It was only then when they were reunited “and kindled a union made stronger by a common love for country and people.”

Lim, a friend of the Echanis couple, posted links of Ka Randy’s favorite songs, including one titled “Sa Pagkakalayo ay May Paglalapit Din,” which the latter helped compose.

Ka Randy was also a fan of the Everly Brothers and their song, “Let It Be Me.” Another favorite is “Mutya,” which was adapted from the classic Kundiman ni Abdon by scientist and activist Aloysius “Ochie” Baes, who became a political prisoner during the Marcos dictatorship.

Ka Randy also listened to ABBA’s “Fernando,” written in 1974 about two former freedom fighters who shared memories of the guerilla war they fought together.

On Linda's request, Lim also posted the YouTube video of “Moon River” sang by Audrey Hepburn. Lim quoted Hepburn’s “Beauty Tips” which were found in the comments section of the post. It says, “For poise, walk with the knowledge that you never walk alone…If you ever need a helping hand, you’ll find one at the end of each of your arms. As you grow older, you will discover that you have two hands, one for helping yourself, the other for helping others.”

“That was the way of life of Randy Echanis and many other dream makers who have become martyred activists,” Lim said.

After getting back Ka Randy’s remains, the Echanis family sought to have an independent autopsy on the body. The probe conducted by forensic pathologist Raquel Fortun brought to light the horror of his murder.

Fortun found multiple “superficial” stab wounds on Ka Randy's body, apart from one deep puncture wound in the back that damaged his aorta and killed him "at once."

The victim’s body had 12 knife-like stab wounds and around 28 pointed punctures, including the fatal one.

There was no gunshot wound, according to Fortun.

She speculated that there was more than one perpetrator and that at least three weapons were used in the crime.

The initial results of the autopsy supported the claim of Linda that her husband was tortured, insisting that the motive was not plain robbery. The final autopsy report has not yet been released.

Linda remains firm that the motive of the killing had to do with Ka Randy's role as a peace consultant and his link to leftist organizations.

Ka Randy’s murder was not a simple death that tugs at one’s heartstring. It leaves a painful imprint that only Linda – his wife, comrade, forever partner – can discern.

Justice is what Ka Linda seeks for her husband for a violent death that no one — not even rebels, and certainly not peacemakers — deserves.

Editing by Lira Fernandez and Norman Bordadora