By JON VIKTOR D. CABUENAS and TED CORDERO, GMA News

November 27, 2020

Eight months into the world’s longest lockdown, the Philippines continues to accumulate debts for its war chest against COVID-19.

Local community quarantines have been in place in the Philippines to curb the spread of the coronavirus since March, but new infections continue to be at the thousands per day, bringing the national tally to over 425,000. The country previously ranked among the top 20 countries across the globe with the highest number of cases.

In August, President Rodrigo Duterte said the Philippines has no more funds for financial assistance, and the government can no longer fund food and financial assistance to those hit by the lockdowns.

Duterte in July also raised the possibility of selling Philippine assets to make funds to procure vaccines against COVID-19 once available.

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Governor Benjamin Diokno downplayed this, however, as he said Duterte was only joking when he raised such a possibility, given the country's healthy gross international reserves (GIR).

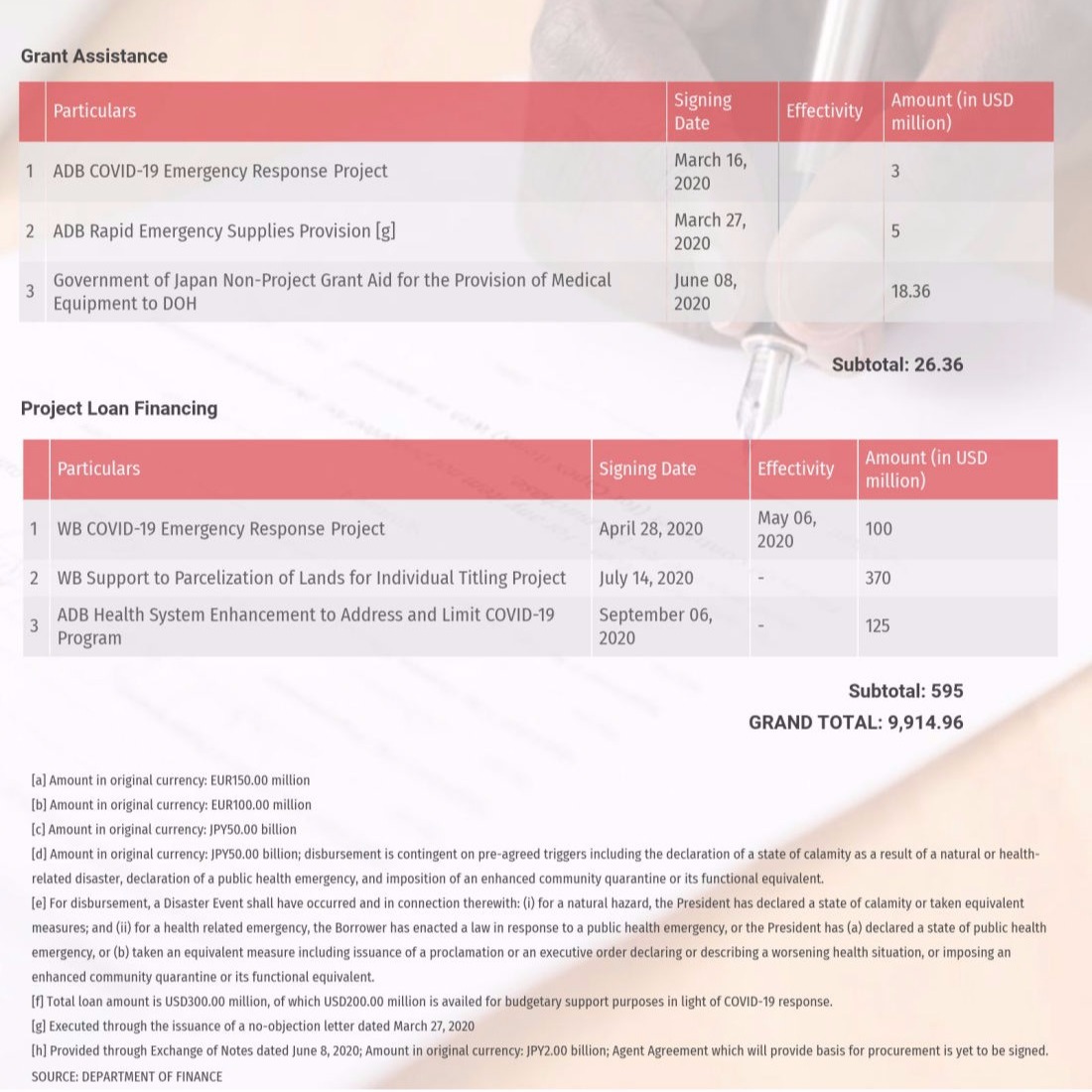

With the pandemic in full swing, the government has ramped up its borrowing program to hit a gross of P3.2 trillion in January to October — the bulk or P2.65 trillion from domestic sources, and P574.4 billion externally.

Locally, the debt consists of P420.309 billion worth of treasury bills, P827.107 billion worth of retail treasury bonds, P561.907 billion worth of fixed-rate treasury bonds, and an P840-billion loan from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP).

The administration’s year-to-date gross borrowings this year will even surpass the P2.815-trillion gross borrowings total in its first three years in power from 2017 to 2019 (P901.67 billion in 2017, P897.55 billion in 2018, and P1.016 trillion in 2019).

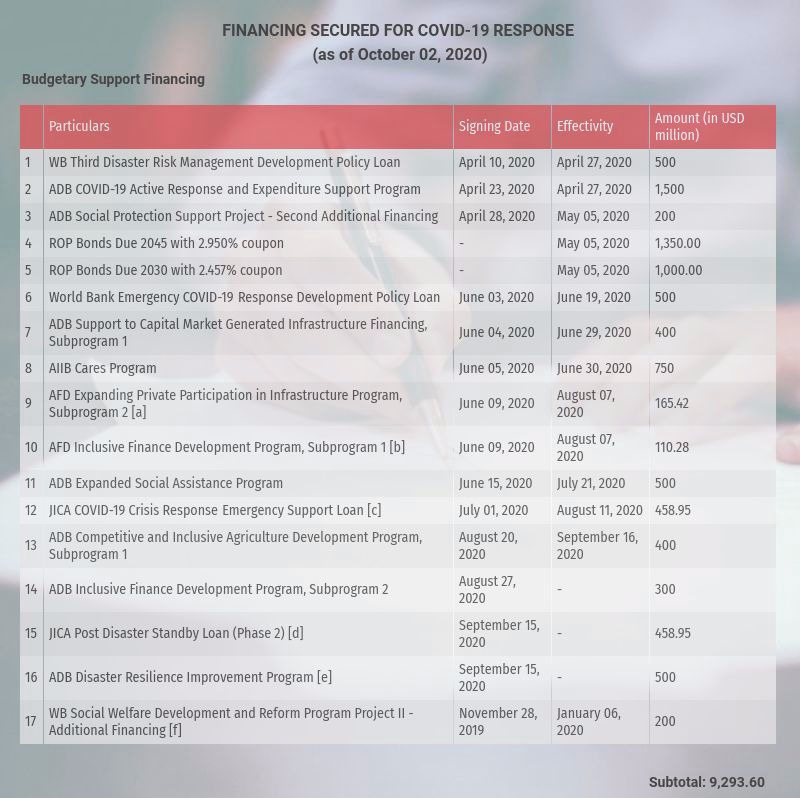

As for foreign loans, latest data available from the Department of Finance (DOF) shows that as of October 2, 2020, the country has so far inked $9.914 billion of financing agreements to finance efforts against the pandemic. This is equivalent to P477.309 billion based on the exchange rate of P48.145:$1 (as of November 24).

Of the amount, $7.93 billion has been disbursed to the government, which means it is now in the state's coffers for use.

Most of the financing agreements — cumulatively worth $9.293 billion — are in the form of budgetary support financing from the Agence Française de Développement (AFD), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the World Bank (WB), and dollar-denominated bonds.

These are on top of the $26.36-million worth of grant assistance received from the ADB for the COVID-19 Emergency Response Project and the Rapid Emergency Supplies Provision, and the Japan Government for the Non-Project Grant Aid for the Provision of Medical Equipment to the Department of Health.

At least three agreements were also inked for project loan financing, cumulatively worth $595 million — two agreements with the WB worth $470 million, and another with the ADB worth $125 million.

The tally does not include the P540-billion loan requested by the national government from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) to provide budgetary support given the deficits due to the pandemic.

Based on the DOF data, budgetary support financing and project loan financing totaled $9.888 billion, or P476.057 billion.

With the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) projecting the Philippine population at 109.947 million, the COVID arrangements would mean that each Filipino owes at least P4,329.88 to pay for such financing agreements, on top of all the other debts the country still has to pay moving forward.

This is equivalent to a little more than eight days’ worth of work for workers in the National Capital Region (NCR) based on the present minimum daily wage of P537 in Metro Manila, which is higher than those earned by workers in other regions.

The repayment period of the COVID-19-related foreign loans is spread from 2023 to 2049, averaging a period of 15 years for each loan, based on amortization schedules in the loan agreement documents available on the DOF’s website.

This means that the next generations of Filipinos will be paying the COVID-19 loans — in the form of taxes — long after the pandemic has passed.

Sonny Africa, the executive director of the economic think-tank IBON Foundation, said the current pandemic-driven crisis faced by the Philippines “actually justifies higher debt-to-GDP levels if this debt is used to support households, meaningfully stimulate economic growth, and especially to structurally transform the economy for long-term development.”

For University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P) senior economist Cid Terosa, the war chest set aside by the government may not be enough to finance the needs of the country as it is only about 2.5 to 2.8% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Other Asian countries have allocated 5 to 20% of their GDP for COVID-related efforts.

“Also, the agreements may just cover at most 50% of the total economic losses of the Philippines due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the inadequate amount to finance COVID-related needs, I believe that the multiplier effects of the current level of government spending can make up for some of the gap in borrowing,” he said.

“I understand, however, that the government has to be cautious in borrowing more funds because of constitutional and budget considerations. Our ability to borrow money to fund disbursements in excess of what has been planned and budgeted is limited by the Constitution,” he added.

Another economist described the government’s response as the most tepid reaction in the region when it comes to the pandemic.

“The size of the war chest buildup may be less of a concern compared to the reluctance to spend. The Philippine fiscal response has been the most tepid in the region with authorities justifying the reluctance in the name of fiscal responsibility and prudence,” Nicholas Mapa, senior economist at ING Bank Manila, said in an email exchange.

He was referring to the P165.5 billion allocated by the administration under the Bayanihan to Recover as One Act or Bayanihan 2, which is smaller than the P389.2 billion allotted in the earlier measure Bayanihan to Heal as One Act or Bayanihan 1.

In October, the government announced that only P4.413 billion from the Bayanihan 2 funds have been released, a figure that jumped to P92.3 billion in November.

“Thus the bigger concern is the lack of urgency to disburse and allocate and less the size of war chest available at their disposal,” said Mapa.

Data from the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) showed it has released a total of P389.220 billion for efforts against the pandemic as of September 14, 2020, from continuing appropriations from the 2019 budget and the 2020 General Appropriations Act. The administration has yet to release a comprehensive itemized list of disbursements of the proceeds from the loans.

The biggest problem with all the borrowing, according to Africa, is about where the bulk of the money is actually going.

“What’s really happening is that the government is using the pandemic as a smokescreen to finance its indulgences – infrastructure, militarism, debt, and lower taxes on the rich. The other side of the coin is that the poor and middle class are made to pay for these indulgences through more and higher consumption taxes that strain their already stretched incomes,” he said.

“It’s where the government isn’t spending to stop millions of Filipinos from suffering or for social services or for building the foundations of the domestic economy. With government debt reaching dizzying heights, this will only get worse in the years to come,” Africa added.

Finance Assistant Secretary Antonio Joselito "Tony" Lambino II did not deny the IBON assertion about the funding being programmed for infrastructure, while inviting the public to check the DOF website, as he assured transparency on financing agreements.

“You will also find it clearly indicated that a number of these agreements are for infrastructure financing. Infrastructure has among the highest multiplier effects in an economy, and creates jobs and stimulates demand. We thus view prudent, timely, and effective infrastructure spending as critical to economic recovery,” he said.

For his part, Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III said that the government's fiscal response is literally adapting to the unprecedented health crisis, and efforts are being coordinated in a whole market approach.

“We have to coordinate health interventions with the fiscal, monetary, economic, and prudential policies to make sure that every detail is in sync with one another. The challenge, of course, is that no one has any prior experience with COVID so we are literally adapting and building our policy playbook,” he said in a press conference on November 18.

“We are really facing a problem of people's confidence in the system and no matter how much fiscal response you have, if people don't have confidence of going out and spending, it's not really going to work, is it? Essentially we are looking at increasing people's confidence in not getting sick and making sure that they understand that the health infrastructure of the government can support whoever gets sick,” he added.

The Department of Finance said it has pushed for the digitalization of public service delivery, which in turn would fast-track the distribution of emergency assistance and other forms of government support, such as the Small Business Wage Subsidy (SBWS) Program, which provides a wage subsidy for employees of small businesses affected by the pandemic. They are given between P5,000 to P8,000 per month for two months, based on the regional minimum wage prevailing in the region.

Dominguez has also assured Duterte that there is enough money for vaccine procurement and storage facilities, as manufacturers have driven optimism that a vaccine could be ready for global distribution in the coming months.

For this, the government has programmed some P73.2 billion estimated to cover some 60 million Filipinos, based on the average expected cost of P1,200 per person.

To finance that, even more borrowing seems to be on the horizon. The Philippines has so far identified three sources for its vaccine fund, P40 billion of which will come from “low-cost, long-term loans” from the ADB and the WB.

It also includes P20 billion from local financial institutions such as the Land Bank of the Philippines, the Development Bank of the Philippines, and government-owned and controlled-corporations (GOCCs); and P13.2 billion from bilateral negotiations from countries with vaccines such as the United States and the United Kingdom.

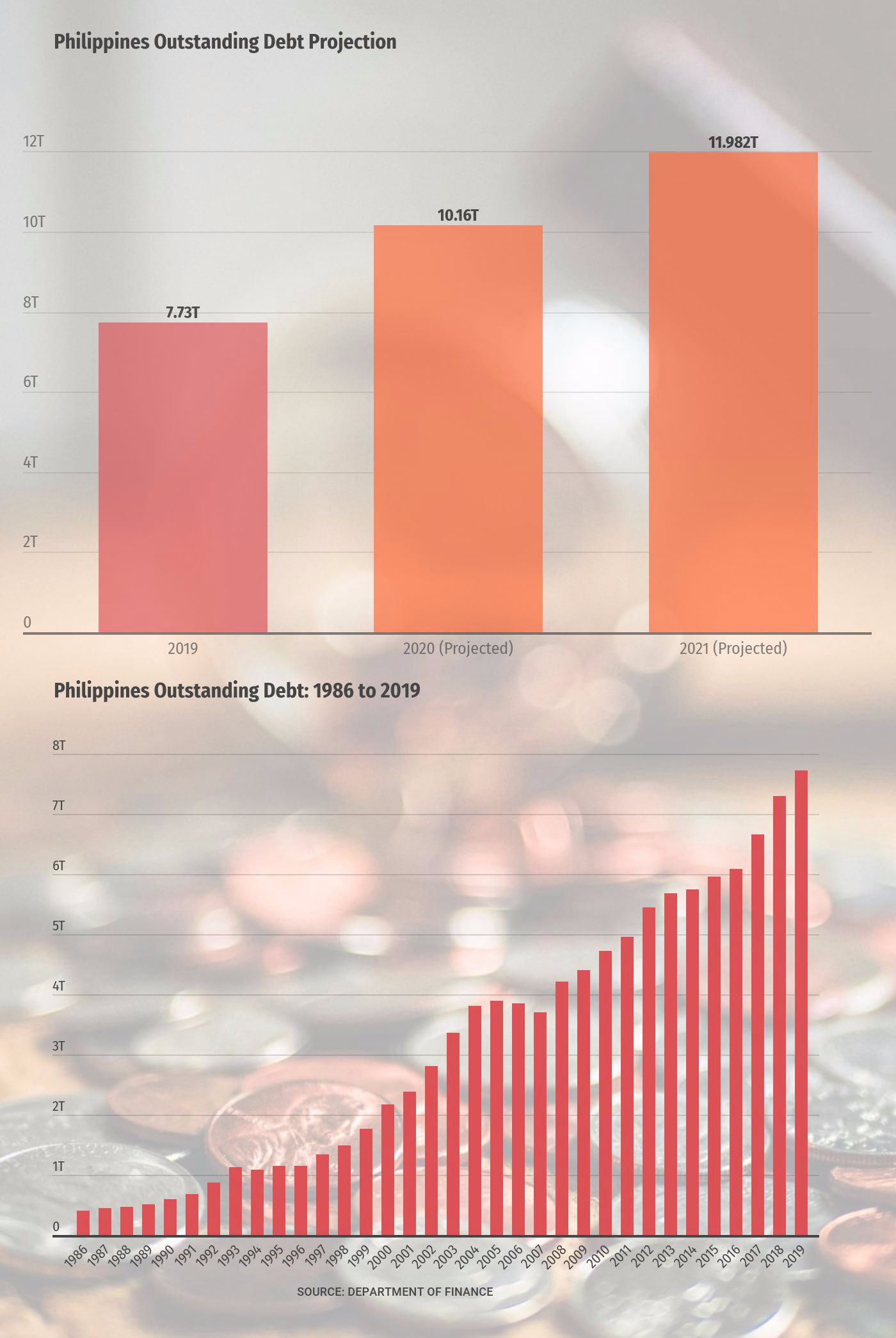

With the government expected to aggressively look for more funds, documents from the proposed 2021 national budget showed that the national government is set to end 2020 with a total debt of P10.16 trillion, 31.42% higher than the P7.73 trillion debt at end-2019. This is seen to increase further by 17.93% to P11.982 trillion in 2021.

Economic managers have continued to qualify that the administration’s borrowing policy is “conservative,” with the latest data available from the central bank showing that the country's GIR of $100.44 billion as of end-August 2020.

The Philippines currently enjoys what are above investment grade issuer credit ratings, as global credit watchers Moody's Investors Service and S&P earlier this year affirmed the country at ‘Baa2’ and ‘BBB+’ respectively, both above the minimum investment grade, while Japan Credit Ratings Agency gave the country its first A rating.

A higher credit rating is generally seen as favorable, as this would give the country lower borrowing costs.

“The Philippines still has leeway to manage higher government spending and wide budget deficits largely for COVID-19 programs and also amid reduced government tax revenues due to COVID-19, while maintaining a delicate balance of having favorable credit ratings, as also seen by the affirmation on the country's credit ratings... despite the economic and fiscal challenges largely brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic,” Michael Ricafort, chief economist at the Rizal Commercial Banking Corp. (RCBC), said in a separate interview.

“Thus, these reflect the Philippines' improved economic and credit fundamentals, as well as improvements in fiscal performance in recent years that could help attract more/bigger roster of international investments and international credit/loans at much lower cost and with better terms into the country, in view of the need to finance COVID-19 programs and other economic stimulus measures needed to help sustain the economic recovery, going forward,” said Ricafort.

Africa is not convinced by the country’s stellar credit ratings.

“It’s worth stressing that credit ratings shouldn’t be misinterpreted as an indicator of development. For instance, as in the case of the Philippines, measures like regressive taxes can improve credit ratings but be anti-development,” the IBON Foundation executive director said.

“Moreover, what credit ratings agencies say shouldn’t be overstated as the sole indicator of manageability. International ratings firms are really only concerned about what they perceive as the ability to repay and being overly concerned about this could straitjacket the Philippines from taking the fiscal measures that the economy and national development demand,” Africa said.

The country's outstanding debt, IBON Foundation notes, would surpass the P11.25-trillion debt incurred in the entire post-Marcos period from 1986 to 2016.

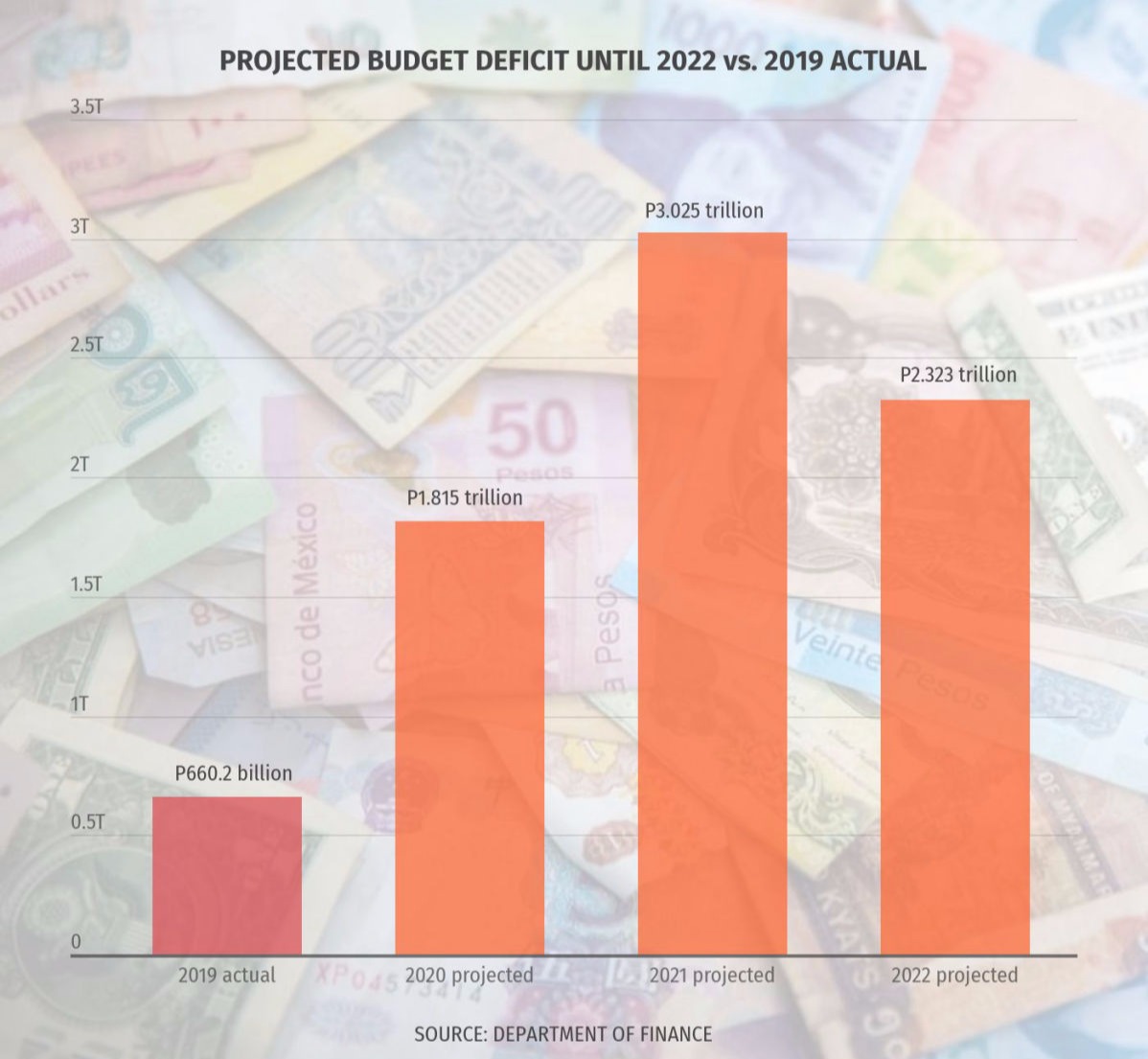

“Measured as a share of the economy, the Duterte administration’s gross borrowings will reach a record 15.9% of GDP in 2020 which is over double the historical average to date of 6.5% and well above the previous peak of 11.8% in 1992. Debt is swelling because, using COVID-19 as an excuse, the Duterte administration is on the biggest borrowing spree in the country's history. It is set to borrow in its six years nearly as much as the five administrations before it did over 31 years,” IBON's Africa said.

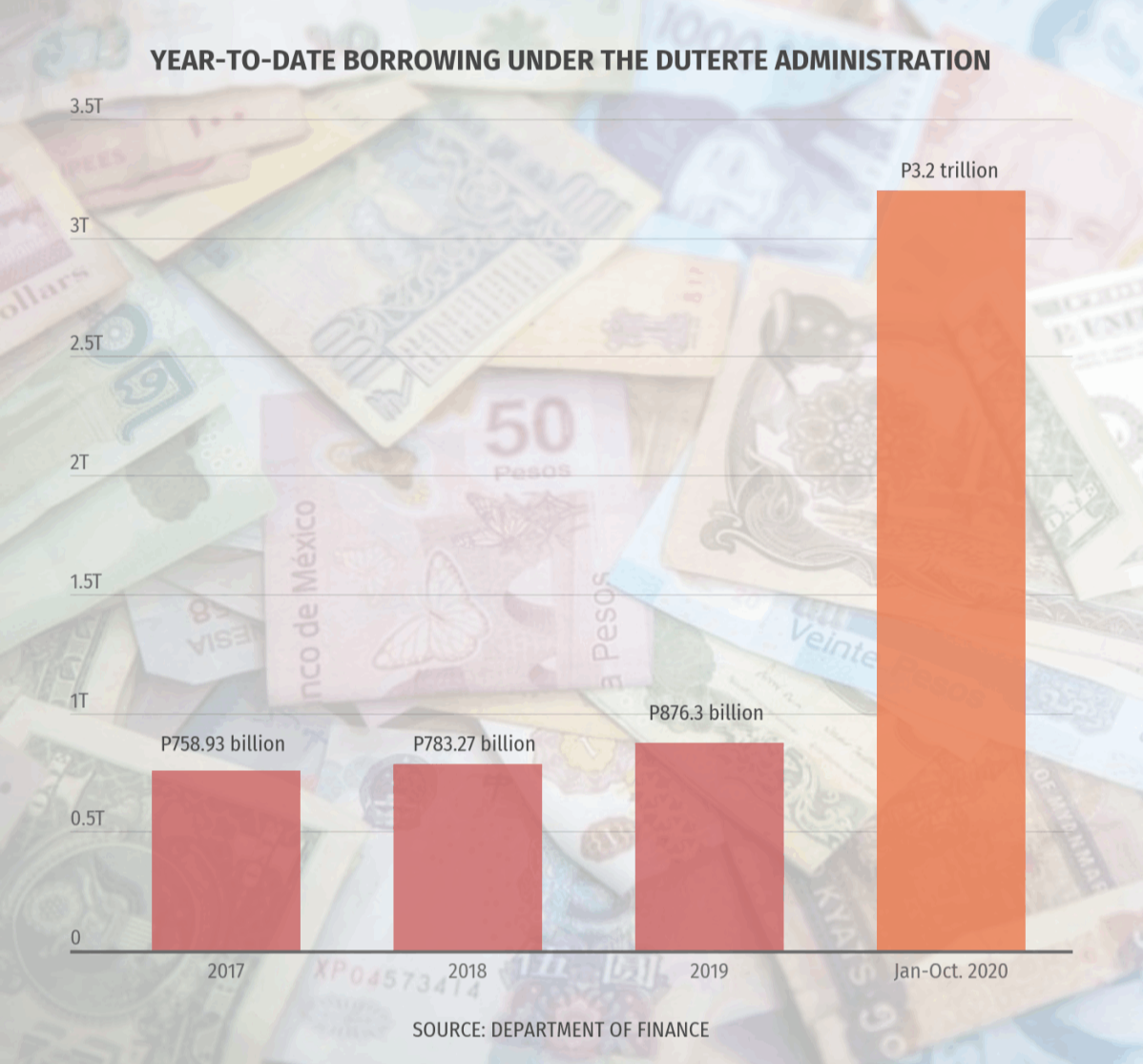

This year alone, the Philippines' debt is projected at P3.003 trillion — P2.218 trillion sourced locally from fixed-rate treasury bonds, and P785.6 billion from foreign sources including project loans, bonds, and other inflows.

Such amount will bring the budget deficit up to P1.815 trillion from last year’s fiscal gap of P660.2 billion, with government spending pegged at P4.335 trillion against lower expected revenue collections of P2.519 trillion.

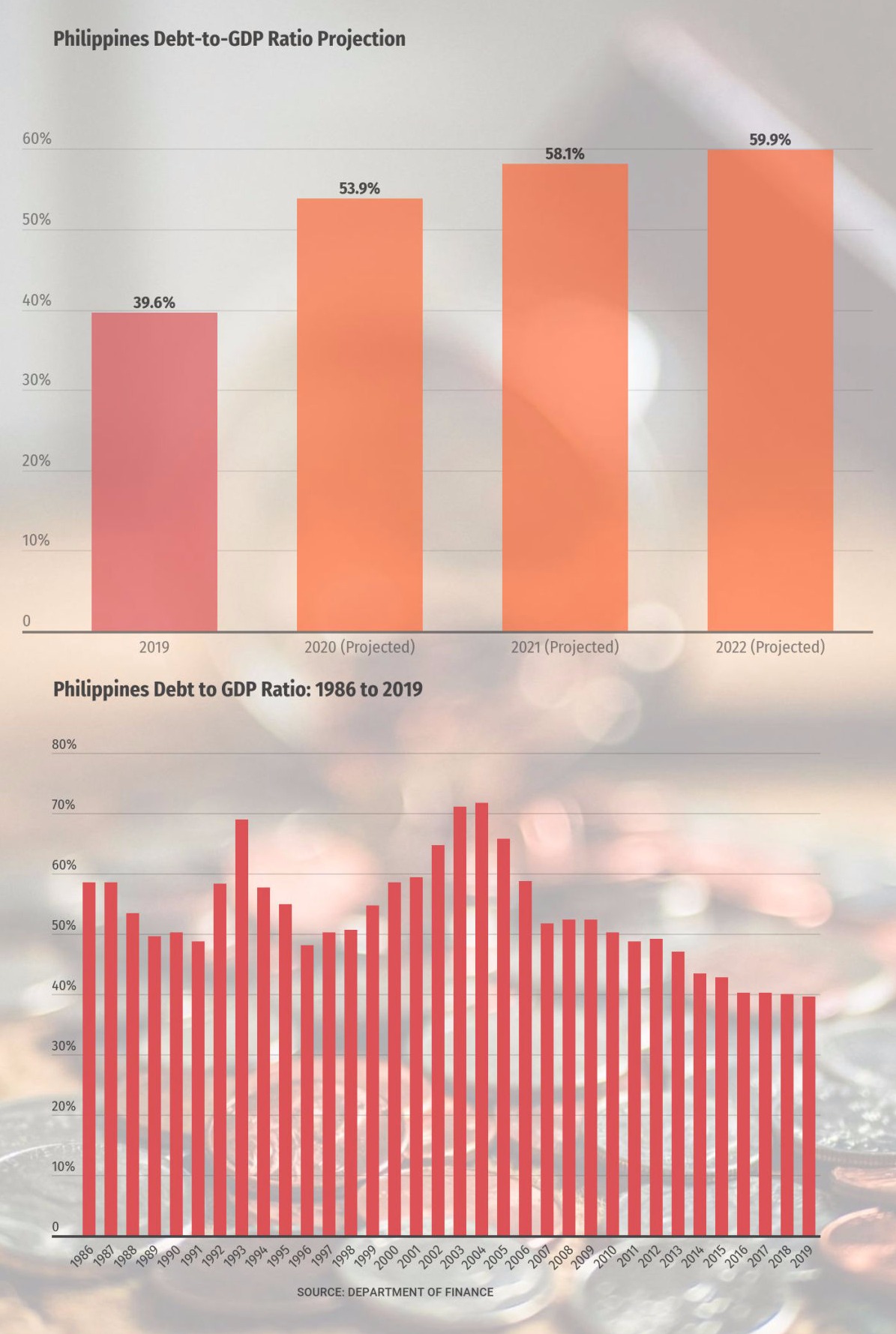

Moving forward, gross borrowings are projected to stand at P3.025 trillion in 2021 and P2.323 trillion in 2022. The government projects that the country’s debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio will spike to 53.9% by the end of 2020 from a record low of 39.6% in 2019, and even higher at 58.1% in 2021 and 59.9% in 2022.

UA&P's Terosa warns of dangers of deficit spending in the long run.

“In the short-run, deficit spending can stimulate the economy. It is imprudent, however, to encourage further deficit spending given the current state of our finances since it will have wide ramifications on the long-run stability of our economy,” he said in an email exchange.

The economist said further deficit spending can raise interest rates, inflation rates, and even taxes, and can deter growth of net exports and lead to deeper trade deficits, and eventually a larger fiscal deficit which could risk the country's credit standing.

The Cabinet-level Development Budget Coordination Committee has maintained that the national government’s debt will be kept at a “sustainable and responsible level” or within the 60% internationally-recommended debt threshold, as the World Bank said a debt level equivalent to half of the size of the economy is still a “safe or manageable” level for the Philippines, as the government intends to increase the debt level to augment funds for COVID-19 response and recovery efforts.

IBON's Africa is not as optimistic.

"In a very meaningful sense, the debt crisis is already upon us — just not yet the kind that the economic managers and creditors are worried about where debt payments to lenders are interrupted. Although the country is certainly much closer to that now than at the start of the Duterte administration," said Africa.