We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

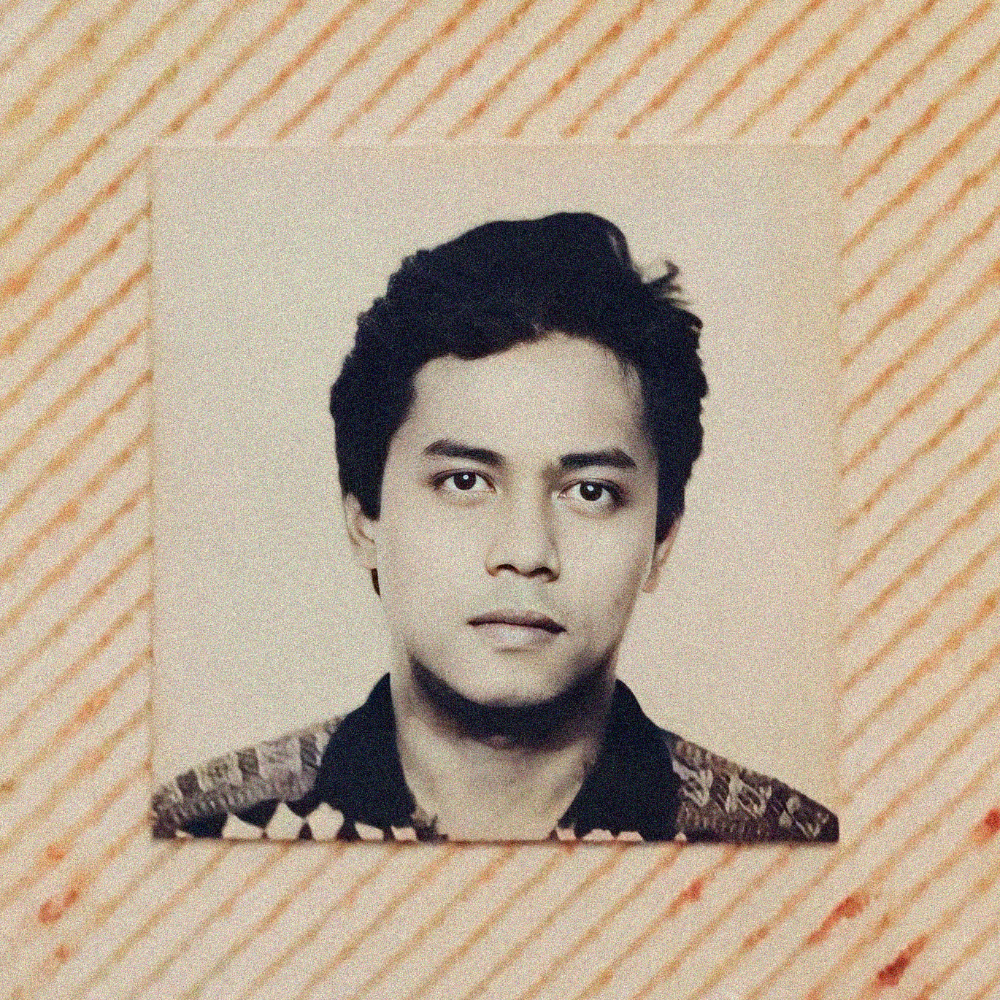

Words by Bernice Sibucao

Art by Yvan Limson | Design by Jessica Bartolome

May 31, 2023

I thought my aunts and uncles had cleaned the room so my sister and I wouldn’t be shocked. It turned out, my dad tried to shoot himself twice.

The first attempt was in that room. My uncle said he probably missed a critical organ. So he tried again, in the upstairs bedroom he used to share with his siblings. I didn’t get to go up into that room. They did not want my sister and I to see the actual scene of my father’s suicide.

It has been a decade, and I am still fixated on the fact: my dad tried to kill himself twice in a single day. What demons could have tormented him to exert such effort to end his life? Was death really his only way out?

I wouldn’t know. He never said goodbye.

“I told your dad that I'll try to petition him,” Tita Myla told me in Tagalog.

We were driving to the Citadel Outlets in Los Angeles. It was September of 2022, and it was my first time visiting her and her family in the United States after they migrated there almost three decades ago.

I was in L.A. to make up for a missed connection in 2019 — I had visited the U.S. for work for the first time then but wasn’t able to make my way from San Francisco to Tita Myla’s place in Long Beach, because I hadn’t realized how big California was.

I had been more prepared this time around, flying to L.A. after a weeklong work trip to Florida. I was able to spend the last few days with Tita Myla and her family who toured me in the city’s museums and theme parks, fed me until the buttons in my blouse burst, and of course, took me shopping.

We were 20 minutes into the ride to Citadel, talking about our family in the Philippines — the fiesta-like reunions in the compound, the short visits to Ilocos — when the topic came around to my father.

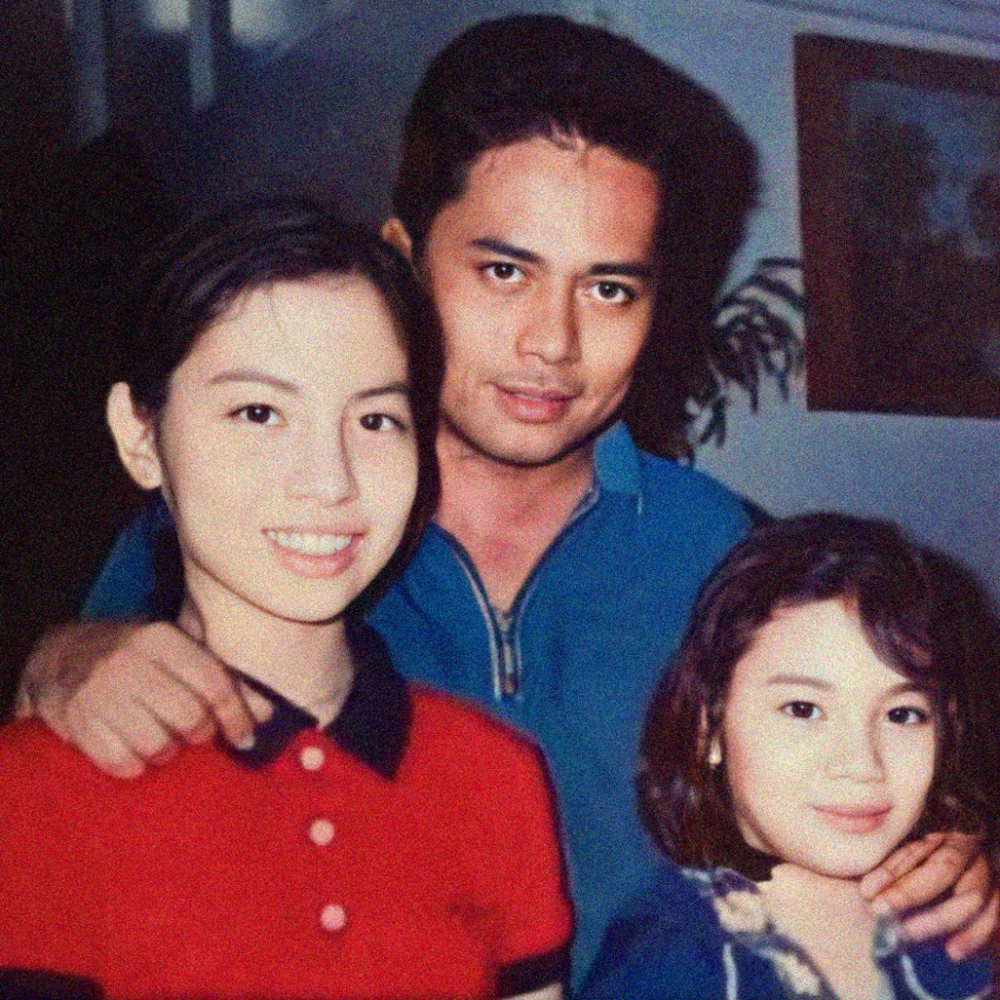

Tita Myla was my dad’s youngest sister. I don’t remember much from when she and her family were still in the Philippines. They had left when I was just beginning to develop memories.

Naturally, my memories of her took the form of phone calls. She would call us every Christmas, always with a smile in her voice, and ask how my sister, mom, and me were doing. She would also chat us to ask what goodies we wanted from the States for her yearly Balikbayan Box delivery. It was always Huy Fong Sriracha for me, Godiva chocolates for mommy, and skin care products for my Ate.

It turned out that Tita Myla had her own set of phone calls permanently recorded in her memories. She chose to play one of them while we’re driving in L.A.’s busy highways — a conversation she had with my father about working on a petition to bring him over.

"That was one of the last times I spoke with Sangko, I think. He said, 'Really?'. He sounded happy and hopeful,” Tita Myla said.

“But he didn’t make it.”

If there’s a movie that perfectly explains how memory works, it’s “Inside Out.” In the film, memories are stored in color-coded orbs inside the Headquarters for Emotions: yellow for Joy, blue for Sadness, green for Disgust, red for Anger, and purple for Fear. The orbs are shipped to the Long Term Memory section where they may stay or eventually fade.

Memory orbs that contain major life events get to stay on a special tray inside the Headquarters. They also shine brighter. They are called core memories.

On March 21, 2013, a core memory formed in me.

Some snippets remain of the moments before the proverbial disaster. The staccato buzz of reporters tapping on keyboards. Sickeningly sweet vendo coffee cooling in a paper cup. Someone ranting about an unresponsive source. Then, my mom calling.

“You need to get home. Your dad had a heart attack.”

A whirlwind of movements and decisions to get from point A to point B. Asking my boss if I could leave early because of an emergency. A worried look on her face. Me, shrugging. “Yeah, something happened to my dad. I’m not sure yet.”

Riding a slow-moving train then a speeding bus. Opening the door of our old Mitsubishi Adventure where inside my mom tells me what she couldn’t over the phone.

“Your dad killed himself.”

'Even though our memories with him were bleak,

I still find myself grieving.'

If you find out that your father had killed himself, after you were initially told that he died of something else, I believe you are entitled to feel more than just shock and grief.

In my case, these two emotions were paired with doubt and annoyance as I asked my mother, “Then why did you say he had a heart attack?!”

She answered in a sheepish tone that provided levity clearly inappropriate for the gravity of the moment, “Well, we didn’t want you to have a breakdown at work.”

Her use of “we” revealed to me that my older sister already knew the truth, even though she was still at the office.

But I couldn’t be too annoyed at my mother. She turned out to be right in her information dissemination strategy because as soon as my sister and I went to our dad’s house later that day, I broke down in tears after seeing the bullet hole in the ceiling. My Ate, meanwhile, calmly asked my uncles and aunt what exactly had happened.

They went on detailing the hows and wondering about the whys of my father’s passing, while an orb shining with bright blue light — Sadness — lodged itself in my memory.

Thousands of miles away and ten years later in sunny L.A., the orb shone again. While my aunt talked about my father, I tried to hold back the tears because dammit, I just wanted to go shopping.

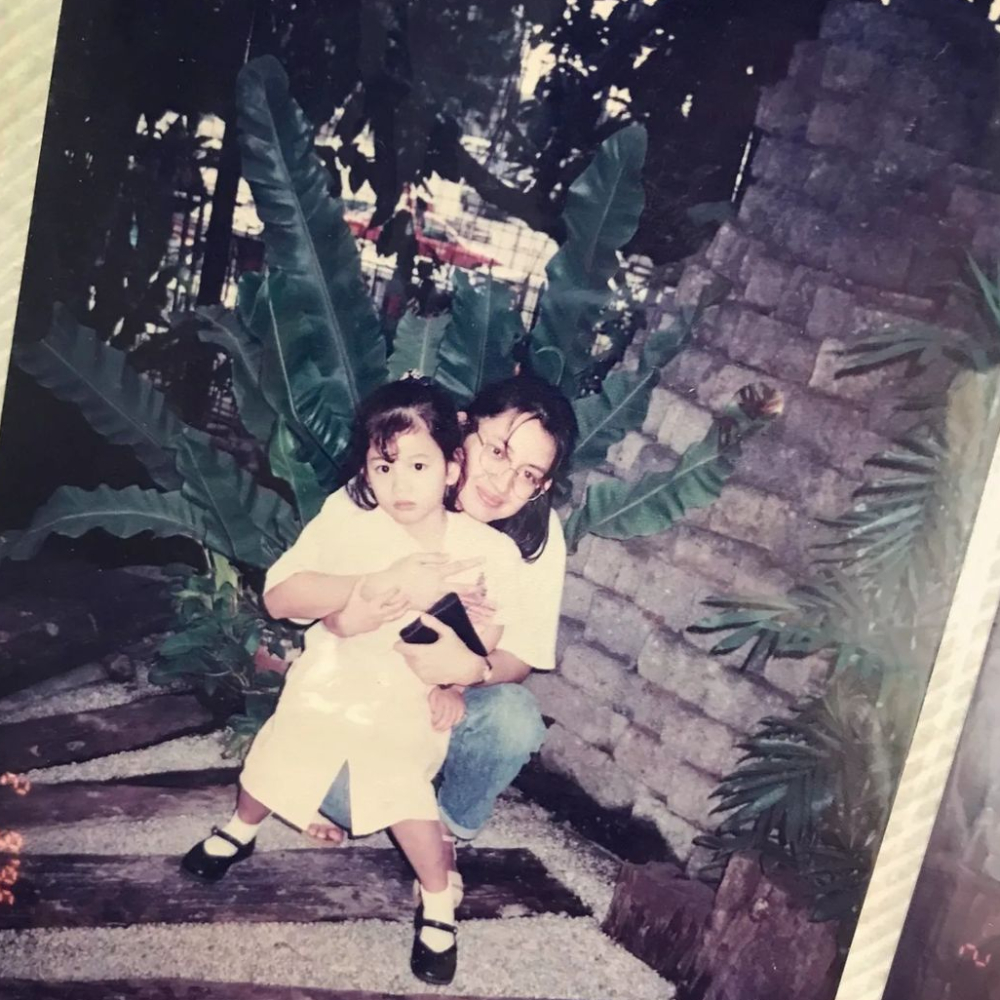

My parents separated when I was seven years old. I had gotten home from school that day when I went into their room and saw my dad’s cabinet open and empty. I asked my mom where he had gone.

“He’ll be staying at your Lola Vita’s,” she said.

My sister and I still saw our dad every week because he had enrolled us in badminton classes. He wanted us to become National Team players, which didn’t happen. We had told him we wanted to play tennis like our grandpa did, but maybe he couldn’t find a decent school, he decided badminton was the next best thing. My Ate and I weren’t really into it.

By the time we reached our teens, our relationship with him became strained. Mutual inattention became our norm.

In high school, my sister and I preferred the company of our friends and busied ourselves with school work and extracurricular activities. Campus paper. Debate team. Dance club. Badminton team. We also had the garden variety teenage rebellion — underage drinking, smoking cigarettes, sneaking out — but many of those vices didn’t stick.

While we were busy finding our way in the world, the chasm between us and our dad grew wider. He became moody, erratic, and aloof, and we really couldn’t be bothered to care. Weekly hangouts at the badminton center turned into the occasional meet-ups, two or three times a year. Birthdays, Christmas, and the odd trip to the mall, often with a curfew set by my mom and grandma.

I never really liked hanging out with my dad.

In “East of Eden”, John Steinbeck wrote about that crucial moment when adults lose a child’s trust:

“When a child first catches adults out — when it first walks into his grave little head that adults do not always have divine intelligence, that their judgments are not always wise, their thinking true, their sentences just‚ his world falls into panic desolation. The gods are fallen and all safety gone. And there is one sure thing about the fall of gods: they do not fall a little; they crash and shatter or sink deeply into green muck. It is a tedious job to build them up again; they never quite shine. And the child's world is never quite whole again. It is an aching kind of growing.”

My dad lost his godly shine on me during a fishing trip when I was 10 or 11.

I had watched the anime “Grander Musashi” on AXN, and I told him I had designs on being an angler like Musashi. He was nice enough to humor that ridiculous notion so every now and then, he would take me fishing at this old abandoned school in Malabon where the flood hadn’t subsided in years, making it home for tilapia and other fish.

I had grown bored of fishing in the same spot and barely catching anything, so one day my dad planned a trip to a lake resort in Bulacan, about 90 minutes away. He said I could bring along my cousin Jeff and friend Marty. All that was left was getting my mom and granda’s permission to take us out of Malabon.

For whatever reason, Dad decided to tell them that we were just going to play badminton at the nearby court. He hid the fishing rods in our badminton bag and told us kids to go along with his plan.

We followed his lead because he was the adult, after all. But I felt anxious throughout the trip. On one hand, we had lied to my mom and grandma. On the other, I knew my dad just wanted me to have a grand time with my cousin and friend.

The day ended with us going home with plastic bags full of freshly-caught tilapia. I gave the bag to my mom, a peace offering for not telling the truth. I had expected to be scolded but my mom just stowed the tilapia in the freezer and told me to eat dinner. There were no hysterics, but her anger was betrayed by her clenched jaws.

I realized then that my dad did a bad thing. In my mind’s view, he began sinking deep into the green muck with all the fish we hadn't caught. As the years passed, he fell deeper and deeper, not because of silly lies of supposed badminton sessions, but because of empty bottles of beer, rum, and other liquor.

When my dad no longer lived with us, he would sometimes call us out of the blue.

The calls would start like this: “My daughter, how are you?!”

He would prattle on about how much he missed us and how maybe we could play badminton some time, or go on vacation together. Then he would ask about school, say he’s proud of us for getting high grades, and insist that we got the intelligence genes from him.

Always, he would always end the call with, “I love you and your Ate so much!”

It would’ve been nice, except of course I knew that the reason he was talking to me in English the whole time was because he was already three sheets to the wind after another day of drinking.

I always found it terribly sad, but also oddly sweet, that the only few times he would remember to call was when he was in a state of inebriation.

My dad was an alcoholic. He would drink almost every day, and there were days he would drink from morning to evening. My aunts and uncles planned to take him to rehab. They always had plans for him. But like with bringing him to America, he didn’t make it.

I never thought of reaching out to my dad during what would become his final days. The last time I spoke to him was via a short text message. It was a month or two before his suicide.

I was a few months into my new job as a Social Media Producer when he reached out. He texted, “Kumusta ka na anak? (How are you?)”

“OK naman po. Medyo busy. (I’m OK. Kind of busy.)” I was preparing to live-tweet a program then.

I’m not sure how the conversation went on after that. To be honest, I didn’t want to talk to him at the time, because he might have been drunk and I really didn’t want to deal with that. So I leveraged my being preoccupied to get out of an awkward conversation.

It would have been our last, apparently. And I’ve always regretted that.

If the present version of me had received his final message, I would tell him, “Hi, dad. I’m OK. I’m kind of busy. But maybe we could play badminton or fish again soon. I love you.”

Or, “I’m sorry that I did not and do not understand you and yet expected so much from you. I wish that you, Ate, and I could try again.”

Billionaires and geniuses in the world have invented all sorts of things that have changed the world forever — vehicles that can fly to space, medicines that can cure illnesses that used to wipe away entire cities, a technology that connects people all over the world in a single click, a gadget that contains almost all the world’s knowledge at your fingertips.

Sadly, they haven’t built what most of humanity wishes for in their hearts of hearts: a machine that would take us back in time.

“It’s no one’s fault,” my therapist told me. I told her I was thinking about writing this piece as a way of reckoning with my dad’s death, ten years after the fact. She said we never really delved into what happened and the aftermath.

It’s true. It’s been five years since I first stepped inside her clinic and the only time I talked about my dad’s death was during that first session. ‘Talk’ may be a generous way of describing it actually. I glazed over the story, acting as if it’s simply one of the many common facts about my life.

I didn’t want to make a big deal out of it because I didn’t want the stereotype. I didn’t want to be “That girl whose dad offed himself so it’s likely she has a lot of unresolved issues. Warning: walk on eggshells.”

Having worked with my psychiatrist for years now, I know she wouldn’t have done that to me. But it remains a reflexive defense mechanism, because once I start thinking about it too much, the floodgates stopping the torrent of guilt, shame, and regret would burst open:

“Why did he do it?”

“Why didn’t he leave a letter?”

“Why didn’t he say goodbye?”

“Could we have helped him?”

“Could we have stopped him?”

“What if?”

“It’s no one’s fault.”

In that meeting when we talked about my dad, I told my therapist, “I have not resolved it yet.” And she said that was OK.

So here I am, clearing my headspace yet still not knowing what to do with my grief, or if I should even do something about it.

What I do know is that after a decade, I am ready to hold up that shining blue orb and examine it in the light.

They say that grief is love with nowhere to go.

I find myself feeling ambivalent about this idea when it comes to grieving for my father because I’m not sure if I even loved my dad, at least not how society would expect me to, given our strained relationship.

In my head, I simplified it like this: If you love someone, then you should miss them when they die. But if I were being perfectly honest, I don’t exactly miss my dad because what was there to miss? He had not been present in our everyday lives. Because he wasn’t there, there was no routine that a child would surely miss once it's broken. There was not much to cling to in the past.

Yet, even though our memories with him were bleak, I still find myself grieving. I still dream about him some nights. In some of these dreams, we are out fishing like we used to do when I was a kid, except the dream version of me is already an adult. Sometimes, I dream of us having lunch, with him cooking papaitan. Every time I wake up from these dreams, I find my pillow soaked with tears.

Maybe I have a very limited understanding of love. Maybe love isn’t just only about ‘what had been’ but also ‘what could be.’ Maybe the love I feel for my dad isn’t held together by wonderful memories from the past, but by the possibility of a future where he is no longer at the fringes, where I am already wise and mature enough to want to and to know how to fix our relationship, and where I now understand that he never stopped being a god because he wasn’t one to begin with. He was just human.

Love was hoping for him. And that hope died when he pulled the trigger, along with the version of me who believed we could play badminton again every week, go fishing and actually catch something decent, and have dinners where he would cook my favorite Ilocano meals.

Love with nowhere to go indeed.