After a lifetime of hoarding, I’ve had to look for my inner Marie Kondo.

More evidence of my cluttered past has just arrived in plastic crates and shabby boxes: vintage, insect-infested newspapers that published my earliest reporting and analog tapes I no longer have the devices to play.

These relics were unearthed from decades-long storage in the home of a beloved (and extraordinarily patient) relative.

Buried among the detritus was a small trove of appointment books.

For those whose adult lives began in the digital age, appointment books were bound paper calendars: one year per volume, divided into weeks, each day allotted a narrow column. They began as pristine pages of promise and ended the year crammed with hand-scribbled appointments, (broken) deadlines, reminders, random notes, ink smudges, and the occasional moldy chip crumb. Unlike journals — which hold sentences, reflections, and the odd stab at creativity — appointment books are almost pure data: unfiltered and gloriously mundane. They record what you needed to do and what happened, not how you felt about it.

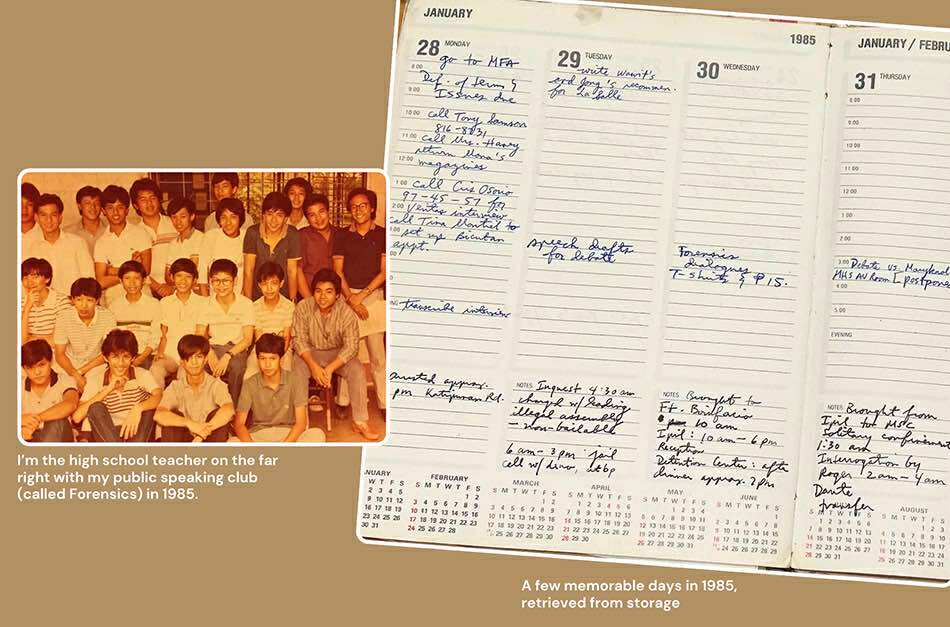

Among the dozen or so rescued appointment books, I kept returning to 1985, a pivotal year in more ways than one, now exactly 40 years ago. Historically, most people will remember 1986, the year of people power and the nation’s return to democracy. But 1985 set the stage for that cataclysm. It was seismic for me personally, as well.

At 23, I was still a rookie high school teacher harboring a gnawing desire to be a photojournalist. I led a kind of double life, and my 1985 appointment book captured it: deadlines for grades, faculty meetings, rehearsals for speech competitions (I was the speech coach) mixed with rallies I wanted to photograph, people I planned to interview, and freelance article deadlines.

Everyone felt some sort of upheaval coming. Ninoy Aquino’s assassination two years earlier hung in the air like smog. Marcos Sr. was ailing but still dictatorial. Something needed to give.

Journalism on the side was my way of understanding the tremors.

So one life unfolded on a secluded, leafy campus surrounded by people younger than me; the other trudged through noisy streets where I interviewed activist leaders who were mostly older.

That double life began in 1984 and carried into 1985, which opened serenely. On January 1, I hiked to a waterfall in Sagada with Mats and Paula, two Swedish travelers about my age whom I’d just met, the giddy feeling of new friendships rekindled by a brief mention in the book. I enjoyed traveling solo in my twenties, exploring at my own whimsical pace a country I barely knew.

Four weeks later, the tone shifted. On January 28, the book records with its usual terseness: “Arrested approx. 5:30 p.m. Katipunan Rd.”

A reminder above it on that date: “Cash paycheck.”

I had been on my way to the bank when a student protest blocked the road. I rushed back to my QC boarding house for my camera and returned just in time to photograph policemen attacking the students with truncheons.

I took 16 shots before an unfriendly hand clamped around my neck. Hauled into a van with terrified students, I was brought to the Quezon City jail, and entered an eight-day disruption my appointment book recounts with chilling brevity:

Jan. 29: “Inquest 4:30 a.m., charged with leading illegal assembly (non-bailable)” Jan. 30: “Brought to Fort Bonifacio” Jan. 31: “Solitary confinement, interrogation by Roger 2–4 a.m.” Feb. 1: “Mom and Dad visit”

On my eighth day, February 4: “Released to the custody of Dad 10 p.m… 8 days, 4 hours as political detainee.”

I was obviously not leading that “illegal assembly,” but the cops probably got orders to arrest the leader. With my large, geeky glasses, I might have looked the part.

I was a victim of false charges, yet I was one of the lucky ones. My parents were well-connected, and I was spared any torture, except for the mental torment of uncertainty. Some might even call my eight days in detention a mere staycation in maximum security. But it exposed me to the system’s deep unfairness. For the rest of the year, to my parents’ initial horror, I plunged into activism, something they eventually accepted, respected, and even admired.

Without this rediscovered appointment book, the rest of 1985 would remain a blur. Now I know whom I reminded myself to call (on landlines or even party lines, in case anyone remembers those) or visit — grandparents, titas and titos long gone, close friends who died too young. Seeing their names as people I could still talk to or drop in on sends a pang of longing through my chest.

As the months wore on, the pages filled with fewer notes about teaching or my social life, and more about the country’s conditions. I visited long-term political prisoners and volunteered with Task Force Detainees; attended meetings of the pro-democracy group Manindigan, led by Jimmy Ongpin; and wrote political commentary for a business paper.

When I wasn’t in the classroom, I was on the streets at rallies and picket lines, sometimes holding a megaphone. Now and then, I’d spot my own students, age 17 or 18, adding their voices to the chants. They had countless other ways to spend their time, but they chose to be there. Perhaps that was the time my double life had merged into a single one.

Seeing young people mobilize today reminds me of those days. We demanded radical change, though no one was sure what form it should take. What we knew was that we had to stay informed and lend our voices to the clamor.

There were disagreements within the opposition, as there are now. But in 1985, we still saw one another at the same rallies, bound by our steadfast rejection of the status quo.

And in February 1986, the dictator fled. Democracy returned in a way no one imagined. The world hailed it as a victory for people power. Many small acts helped make it possible.

Forty years later, my old appointment book shows how relentless those efforts were. But the strongest memory is how none of it felt like work. For many then, as for many now, it was simply a calling.