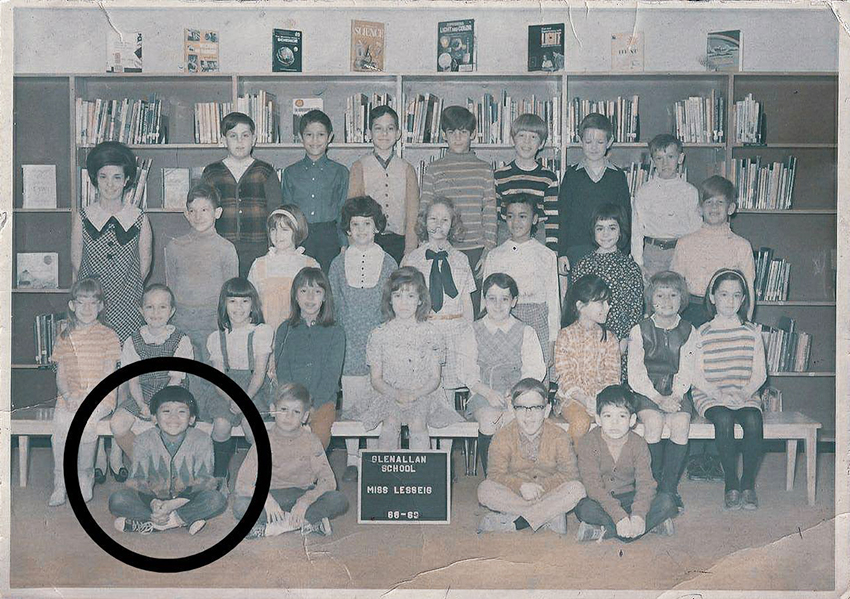

I grew up a “third-culture kid,” long before I knew the term existed.

When my family returned to the Philippines during martial law, I was 12 years old and labeled a balikbayan, a word still novel then. But I knew I wasn’t simply a returnee. Unable to speak my native tongue and having spent my formative years abroad, I felt like a fish out of water, a feeling that had followed me for much of my young life.

In America, I was one of the few kids of color in my school and was occasionally subjected to racist teasing. Back in the Philippines, at my new elementary school, I became self-conscious about my American accent and my cultural ignorance. At one class picnic, I poured vinegar on turon, mistaking it for lumpia, and everyone laughed, including the teacher.

Fortunately, in high school, I had brilliant, nationalistic teachers. It was then that I decided I would embrace my Filipino identity.

I still spoke halting Tagalog, but I deliberately put myself in situations where English wasn’t an option. Well into young adulthood, my vocabulary remained limited, my idioms awkward, and my written grammar often flawed. English was my strength; Tagalog, my Achilles heel. But the fish had adapted to a new ecosystem. This was where I belonged.

By the 1990s, when I was already working as a journalist, the term “third-culture kid” had come into vogue. It finally gave language to what my siblings and I had been growing up — people shaped by multiple cultures — though by then we were certain of our primary identity as Filipinos.

The 1990s were also when I ventured into television as a reporter on The Probe Team, shortly before it transitioned from English to Filipino after a decade on air. Coached by patient and talented colleagues, I learned to write and voice scripts in Filipino, though I sometimes drafted them first in English and sought help with translation.

I have now been with the documentary program I-Witness for 23 years, writing and narrating exclusively in Filipino. In exploring the country through that show, I like to think I have also answered, in my own way, the challenge of cultural ignorance.

Lately, when given a choice, I have begun delivering speeches in Filipino. At a university commencement this year, where the rest of the ceremony was conducted in English, I chose to speak in Filipino. I knew the students spoke Filipino in everyday conversation, and I felt that addressing them in the vernacular would resonate more deeply.

A recent invitation brought everything full circle. I was asked to speak at an event honoring overseas Filipinos who had excelled in communications and media, organized by the Commission on Filipinos Overseas.

The young awardee seated beside me at dinner was a third-culture kid who had just decided to move to the Philippines. He was still learning to speak in Filipino. That was me, several decades ago.

Now, many years later, I found myself confident enough to deliver my speech in our native language — to proud Filipinos from across the world.

An excerpt:

Ipinagdiriwang natin hindi lamang ang tagumpay ng bawat isa sa inyo, kundi ang kuwento ng isang bansa na patuloy na hinuhubog ng mga anak nitong naglalakbay sa malayo.

Kayo ang mga tagapagkuwento sa panahong ang katotohanan ay madalas malunod sa ingay. Kayo ang nagpapatunay na kahit na nasa ibayong-dagat, kayang maging tinig ng isang bansang patuloy na naghahanap ng katarungan, liwanag, at direksyon.

Hindi bago sa kasaysayan natin ang ganitong tungkulin. Sa Europa sa ibang siglo, may isang pangkat ng mga Pilipinong naglakbay din sa malayo — hindi para humanap ng trabaho, kundi para makaranas ng kalayaan. Sina Jose Rizal, Marcelo Del Pilar, Lopez Jaena, at iba pa, na nagtipon-tipon sa Espanya, ay nagsulat para sa La Solidaridad, isa sa mga unang pahayagang tunay na makabayan. Sa pamamagitan ng kanilang panulat, naipuwesto nila ang umuusbong na Pilipinas sa gitna ng pandaigdigang usapan tungkol sa karapatang pantao, demokrasya, malayang pag-iisip, at kalayaan sa pamamahayag.

Sa madaling salita, sila ang unang “overseas Filipino media practitioners.”

At ngayon, kayo ang nagpapatuloy ng kanilang tradisyon — sa mga bagong plataporma, para sa mas malawak pa na komunidad, ngunit taglay pa rin ang parehong layunin: ang maghatid ng katotohanan at magbigay ng tinig sa mga walang tinig.

(We are celebrating not only the achievements of each of you, but the story of a nation continually shaped by its children who journey far from home.

You are the storytellers in a time when truth is often drowned out by noise. You prove that even while overseas, one can still be the voice of a nation that continues to seek justice, light, and direction.

This role is not new in our history. In Europe, in another century, there was a group of Filipinos who also traveled far — not to look for work, but to experience freedom. José Rizal, Marcelo del Pilar, López Jaena, and others who gathered in Spain wrote for La Solidaridad, one of the first truly nationalist newspapers. Through their writings, they placed the emerging Philippines at the center of the global conversation on human rights, democracy, free thought, and press freedom.

In short, they were the first “overseas Filipino media practitioners.”

And now, you are carrying forward their tradition — on new platforms, for an even broader community, but still guided by the same purpose: to deliver the truth and to give voice to the voiceless.)