American football is so American it’s the only major sport that has the word American baked into its name. Of course, it’s called “American football” only outside America, because nearly everywhere else football — or “futbol” — is a completely different sport, played mostly with a ball at your feet, hence the name “football.” Get it?

American football, on the other hand, is played primarily by throwing, holding, catching and blocking a ball with your hands. A more apt name would have been “handball,” but that’s already taken by another, far more obscure sport. So Americans appropriated “football” even if it didn’t make much sense and even if it was already taken by another sport played around the world. What is football in other countries is not even football in the US but “soccer,” one of the few countries where it’s called that.

Despite American football’s immense popularity (number one sport on its native soil) and the marketing muscle of American sports, American football has not exactly caught on globally the way those other major American sporting exports have: basketball and baseball.

I’m not really sure why American football failed to take root even in former US colonies like the Philippines and Puerto Rico, but my own brief childhood experience playjng the sport may offer some clues.

While growing up a fan of football — the American kind — on the snowy east coast of the United States, I tried out for a local youth team. Not even five feet tall yet, I loved how imposing I looked in shoulder pads. But when my mom saw the kid behemoths who would be tackling me, she urged me to switch to baseball, which I dutifully did. (I recall Mom calling the sport “bakbakan”).

There’s a reason (American) football players wear helmets and pads. They are modern-day gladiators, playing what may be the most violent sport in the world that doesn’t involve animals — assuming we even count cockfighting and bullfighting as sports. Stadiums packed with drunken fans roar as helmeted bodies collide with such force that the impact echoes into the stands, like cinematic Roman arenas where an earlier empire staged lethal swordplay for the masses.

Concussions in American football are so common that the sport has a dedicated protocol for them, and many players develop serious brain diseases long after their careers are over.

One might call these twin facets of American exceptionalism that U.S. diplomats rarely boast about: the appropriation of the global game’s name — “football” — and the unapologetic brutality with which their version is played.

The pinnacle of the sport is the Super Bowl, a championship game so culturally overloaded that the halftime show is often anticipated as much as the game itself. It is the quintessential American spectacle, fusing the country’s most popular sport with its biggest entertainment stars.

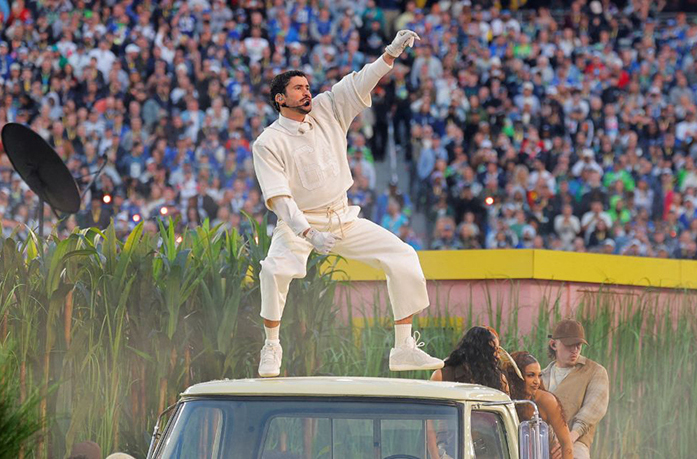

Strutting onto the Super Bowl halftime stage last Sunday was the biggest star of them all: Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican artist fresh off a Grammy win. He danced through lush tableaus that evoked his native island and performed songs celebrating Latino culture — all in Spanish. Bad Bunny wasn’t making a statement by singing in Spanish. He always does.

Choosing the world’s most popular act for the Super Bowl was, on its face, a rational business decision. But it also felt like a masterstroke of trolling — aimed squarely at the loud minority that cheers on ICE and its ruthless hunt for immigrants, most of them Spanish-speaking.

The MAGA kingdom promptly erupted. Some even demanded that Bad Bunny be deported. The small problem with that is that Puerto Ricans are born American citizens. They have just as much right to be on U.S. soil as any MAGA talking head — Bad Bunny’s thick Puerto Rican accent notwithstanding.

The whole hullabaloo got me thinking about how we all got here.

Puerto Rico and the Philippines share an oddly parallel history: both were Spanish colonies, both were taken over by the United States, and both became U.S. possessions under the same deal that ended the Spanish-American War.

After that, their paths sharply diverged. The Philippines, four decades after the bloody Philippine-American War, successfully lobbied for independence. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, evolved into a U.S. “territory” — a political gray zone, short of statehood and stripped of full voting rights.

Although Puerto Ricans are American citizens, this lack of political power, combined with a long history of neglect, has fueled resentment and periodic calls for independence — more than 80 years after the Philippines gained ours.

One irony of this shared colonial heritage is linguistic. The Philippines fully embraced the language of its last colonizer. English became our medium of instruction and a passport to upward mobility, even long after independence.

Puerto Rico, by contrast, remains overwhelmingly Spanish-speaking. Over a century into U.S. rule, many Puerto Ricans still grope for words in English — as Bad Bunny did, unapologetically, on the Grammy stage.

That attachment to Spanish, and the lack of effortless English, have made it easy for bigots to blur the line between Puerto Rican American citizens and undocumented Latino immigrants.

In a sense, Bad Bunny exacted revenge for his people on America’s biggest stage.

He didn’t bother performing a single English-language song. In his finale, he led a parade of flags, recited the names of many nations in the Americas — including the United States — and declared, ““Together, we are America.”

Clever, I thought.

On behalf of everyone from Canada to Chile, at a thorny moment in history, he boldly laid claim to the word “America.” It’s not the USA alone.

And why not? It makes no less sense than inventing a sport dominated by hands and calling it “football.”