Of all the things that could reconnect me to our pre-colonial roots, I never expected it to be a pack of naked young men sprinting across a university campus. But somehow, now, it makes perfect sense.

Nearly two decades ago, I covered the annual Oblation Run at UP Diliman for Sidetrip, my travel-and-culture segment on GMA-7’s Saksi. That happened to be the year the APO fraternity’s tradition was unexpectedly upstaged by two masked women who went topless and posed by the Oblation statue near the campus entrance. Naturally, the media horde, and much of the crowd, rushed toward this feminine break in tradition.

As APO “brads” explained to me, running in the nude began in the 1970s at the height of martial law, originally as a protest against censorship. They had to sprint to avoid being caught by security. What was once shocking is now a tolerated, even eagerly awaited, spectacle, captured by hundreds of mobile phones every year.

Like many, I noted the irony: this annual birthday-suit event was inspired by a statue that wasn’t even fully naked. Before its unveiling in 1935, a fig leaf was placed over the Oblation's solid bulge, while the masked runners let their manhoods jiggle freely. I suppose a future, even bolder batch of brads may eventually ditch the masks too.

I was reminded of this fig-leaf modesty when I received a series of emails from a retired Filipino-American named Sylvester Salcedo. He has been campaigning to liberate the Oblation from its fig leaf and display its nudity in full, the way the runners do every year.

For him, the gesture is symbolic, not a fetishistic fixation on a pre-war statue. Salcedo argues that we must strip off the fig leaves from our colonized selves and reclaim our indigenous humanity.

In the textbooks used by fine arts students in the Philippines, the canonical male nude is still overwhelmingly Caucasian, modeled after the Renaissance ideal, Michelangelo’s David, perhaps the most famous nude of all.

In a recent I-Witness documentary, my team and I traced the origins of the Oblation, that figure with outstretched arms and skyward gaze perched before the university’s administration building. It has welcomed generations of scholars, standing atop a pedestal inscribed with lines from Rizal dedicated to the nation’s youth.

The sculpture seen on campus today is actually a bronze replica of the concrete original kept inside UP’s main library, which has been under renovation for several years.

Both bronze and concrete Oblations were created by Guillermo Tolentino, the Philippines’ pre-eminent sculptor who was proclaimed a National Artist in 1973.

Tolentino, trained abroad in classical techniques, used Filipino models for the Oblation (despite persistent rumors, FPJ Sr. was not one of them).

According to art historian Rod Paras-Perez, who wrote Tolentino’s definitive biography, the original concept was for a completely nude figure. But a conservative former UP president, Jorge Bocobo, insisted on the fig leaf.

According to Toym Imao, the current dean of UP’s College of Fine Arts and himself the son of a National Artist, the fig leaf was an act of censorship of Tolentino’s artistic vision.

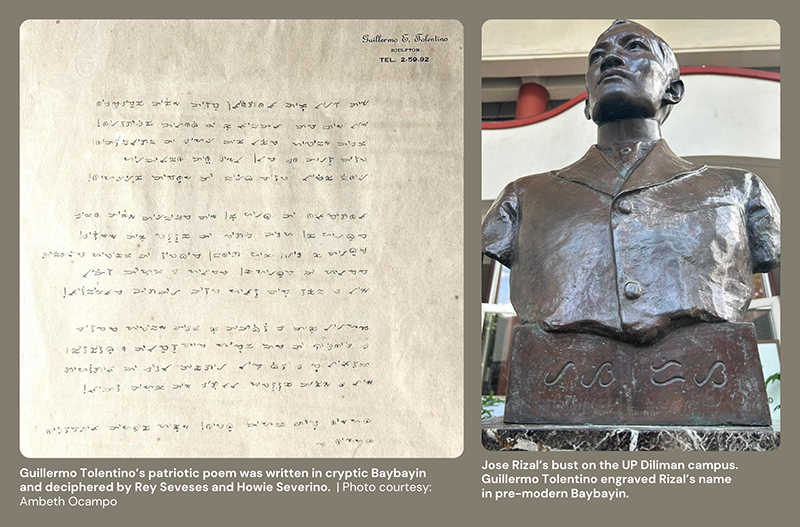

The Oblation isn’t the only Tolentino piece that greets students at UP Diliman. A bust of José Rizal has stood guard at the entrance of Palma Hall since the 1950s. What struck me most — aside from the uncanny likeness to the national hero — was Rizal’s name inscribed in Baybayin, rendered in the oldest known form of the script.

Intrigued, we made our way to the Guillermo Tolentino hall at the National Museum, where nearly two dozen of his portrait busts are on display. Among them are Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo, Manuel L. Quezon, and Ramon Magsaysay. Each was rendered with Tolentino’s unmistakable realism, their stoic faces fixed with a gaze that hints at minds caught in mid-thought.

Nearly every one of them — interestingly, Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. was an exception — included their names in Baybayin script etched into the base.

Through further reading, I discovered that Guillermo Tolentino was a staunch advocate of Baybayin, not merely immortalizing it in his art but actively using it in his daily life — for taking notes and otherwise employing it as a fully functional writing system. For Tolentino, our native script was not just an aesthetic or decorative element; it was a living medium. He is, as far as I know, the only prominent Filipino artist who was fully adept at using our pre-colonial script.

It was as if he wanted his art not only to depict Filipino themes but to think in Filipino. Though trained in classical European techniques, he featured Baybayin in his work — a testament to a literate and sophisticated culture that existed long before Magellan arrived.

As Filipinos, we are taught only the Roman alphabet, often forgetting that it is a foreign script developed in Europe to express European languages. Tolentino reminds us across generations that our ancestors bequeathed an elegant, indigenous script — a phonetic syllabary that flows naturally with the rhythms of our language. Like Rizal and other nationalists, Tolentino saw the revival of our native scripts as a vital act of cultural reclamation and decolonization.

That realization, combined with his exquisite artistry, was enough to make me a diehard Guillermo Tolentino fan.

Then, out of the blue, I received a message from the eminent historian Ambeth Ocampo, a longtime collector of Tolentino’s works.

Ambeth had seen my documentary on the Oblation, which reminded him of a trove of Tolentino papers in his possession. He sought my help in translating something handwritten by Tolentino in Baybayin.

The text covered an entire sheet of Tolentino’s personal stationery. It was given to Ambeth by the artist’s widow, along with other papers. Seeing something so extensive written in Baybayin by a famous Filipino artist was exhilarating to me. Yet, even though I could recognize the individual characters, the text made no sense to me. It seemed almost indecipherable.

I reached out to my high school classmate Rey Seveses, to whom I had introduced Baybayin years earlier. Rey had since become something of a Baybayin savant, able to translate even the most intricate calligraphic versions of the script.

It didn’t take long for him to send me the translation, after unraveling Tolentino’s unusual formatting: he had written the text from right to left! I had never seen Baybayin presented this way. He had made it challenging even for experienced practitioners like myself.

Hidden in plain view was Tolentino’s heartfelt patriotic poem in Tagalog. Here is Rey’s translation of the untitled and undated poem from Baybayin to Roman script:

Ang lahat ko'ng panaginip

Mulang aking kamusmusan

At ang mga pangarap ko

Ng binatang kasiglahan!

Isang araw'y makita kang

Hiyas ng igatsilangan

Walang luhang nasa mata

Taas noong nakatunghay

Hindi kimi't walang bahid ng kahihiyan

Panagimpan ng buhay ko

Ang masidhing aking nais

Mabuhay ka

Yaong sigaw

Ng kaluluwa kong aalis!

Mabuhay ka oh

kay ganda

Mab'wal nang ikaw'y matindig

Mamatay nang mabuhay ka

Mamatay sa iyong langit

At sa dakila mo'ng lupa'y

Walang hanggang mapaidlip!

Dayata't kung sa libingang ko

Isang araw'y mamalas

Sa sinsin ng mga imus

May lumutang na bulaklak

Ilapit mo sa labi mo't

Hagkang taos ng pagliyag

At sa aking kaluluwa'y

Tatagos ang iyong langit!

Bayaan mo'ng iyang buwan!

Ako'y kanyang pagmalasin

Bayaan mo

My humble translation into English language and Roman script:

All of my dreams

Since childhood,

And the ones I have held

In the vigor of my youth!

One day to see you

the jewel of the East

With no tears in your eyes

Head held high

Neither hesitation

Nor hint of shame

The dream of my life

My most fervent desire

Is that you may live

This is the cry

Of my departing soul

Live on oh how beautiful

Fall so that you may stand

Die so that you may live

Die in your own heaven

And upon your noble soil

Find eternal rest!

Perhaps at my grave

One day you may behold

Amid the thickness of weeds

An emergent flower

Bring it close to your lips

With true affection

So your heaven

Will pierce my soul

Let the moon be!

Let it gaze upon me

Let it be…

Perhaps this was the “emergent flower amid the weeds” in Tolentino’s poem — his long-lost appeal from the grave to love our country without shame. In that revelatory moment of first reading, it felt as though the Oblation Run itself had delivered this flower to us.