We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

The author takes a selfie in his hospital bed. He tested positive for COVID-19 and had to be confined at a government hospital. Joe Galvez

“Of all people, why me?”

That was the question on my mind. I have never left the house since the COVID-19 lockdown in the Philippines began in March 2020. I may not be of perfect health, but I figured going more than a year and a half without being stricken by the virus was quite an accomplishment. It meant that my family and I followed health protocols to the letter. I had just been given my second dose of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine a month ago, which is why I was quite confident I wouldn’t be stricken.

But in the second week of August, I began having a dry cough, as did my wife. To be sure, I had a swab test taken on August 27, 2021. The next day, the hospital that conducted the test texted me that I was positive.

I needed to be admitted and confined immediately.

The following morning, a Sunday, the municipal ambulance brought me to a government hospital in Balanga City in Bataan for immediate treatment, through the recommendation of our municipal health officer and other health care workers.

The ambulance ride from our town to the city was not as comfortable as some may expect. Our town’s ambulance was old and rickety; the air-conditioning was broken, and while it was miserable for me, I could just imagine how much worse it was for the driver and the medical worker, both clad in hazmat suits, as they rode with me for some 28 kilometers to the hospital.

Upon reaching the medical facility, we were told to wait almost 30 minutes before we were even allowed entry. From there, a male nurse, also in a hazmat suit, ushered me on a wheelchair into a worn-out white tent, where I joined other COVID-19 patients awaiting confinement. There, we all had to wait until rooms and beds became available.

“Welcome to Zombieland,” I thought to myself looking at the patients waiting, which now included myself.

In my long career as a photojournalist, it was perhaps the most depressing scene I have ever encountered of people waiting in the hospital. Some were in pain, while others just aimlessly stared at our fellow patients — perhaps they were mesmerized and confused as to where they were and what was happening to them. Thankfully for myself, as a veteran journalist, my experiences have steeled me for the desperation that surrounded me.

A COVID-19 patient’s leg dangles still from the side of a gurney. This was one of the many glimpses I saw and photographed as a fellow afflicted. In my hospital stay, I saw pain, agony, suffering, and death. Joe Galvez

I had to close my eyes as I began to feel the heat inside the soiled isolation tent. I was given my first taste of hospital food. It was bland, as expected.

The tent had two big air-conditioning units, but the heat inside still remained unbearable. The stains on the tent’s walls betrayed just how tough times had been through the whole pandemic, from the beginning in 2020 to the Delta variant episode happening today.

I waited for about two hours before I was finally told that there was a room ready for me. It was the first bit of welcome news I had received in a while. I felt relieved.

The room was big, and had its own comfort room. I had to share the space with three other patients, all of them dealing with COVID-19.

Yellow and black plastic bags with discarded medical waste are quick to pile up. A peek outside the building shows the hospital's waste treatment facility with a truck already filled up to the brim. Joe Galvez

I didn’t expect the stay to be pleasant or luxurious, but I was still surprised by the state of the room. Still, I figured, there was only one important choice: live or die.

The atmosphere inside the hospital wasn’t that impressive, but then again, what can I expect from a government hospital? But I also noticed that there seemed to be an ample supply of medicine and hospital equipment. That gave me confidence and allayed some of my fears.

After two days in confinement, I saw more glimpses of my new world opening up to me.

Medical waste inside yellow and black plastic bags were piling up. A peek outside the building showed the hospital’s waste treatment facility, with a truck already filled to the brim. I noticed that waste bags are safely stored in a concrete storage structure.

I began to wonder where and how the hospital waste are properly disposed. I hope the facility has an eco-friendly waste disposal system.

A scene from across my hospital bed: a healthcare worker in a hazmat suit going about their duty. I could just imagine the sweat they generate inside their protective clothing, which they end up wearing 10 hours a day. Joe Galvez

After my rumination about hospital waste, I went go back to my hospital bed where a serving of hospital diet food was waiting. The food is usually prepared by nutritionists for patients with a variety of illnesses, but it’s certainly not a delight for the palate. Luckily for me, my daughter always ordered food from outside for my daily sustenance throughout my confinement. It also helped having a variety of tsitsirya on hand. Fruits, too.

While the food is something I expected, the serenity — or lack thereof — was something that surprised me.

Nurses communicate with each other at the top of their voices. I couldn’t blame them. The hazmat suits that they had to wear from head to toe probably impaired their hearing. Delirious patients, too, made weird sounds just to attract the nurses. The noises they created disturb the stillness and the sanctity of the hospital rooms and corridors.

Still, what could I expect from a hospital already overwhelmed by so many victims of COVID-19, especially with the Delta variant?

Two nurses in hazmat suits prepare a COVID-19 patient for dialysis treatment. Joe Galvez

A nurse told me that the hospital is now divided into two units: the green zone and the red zone.

The green zone is a “safe” space for the hospital, where only patients who do not have COVID-19 could be accepted for confinement.

I was in the red zone, which was having a hard time absorbing the influx of COVID-19 patients. All the beds were already occupied.

The blood extractions seemed endless, and I grew reluctant to give more samples as time went on. Twice a day, antibiotics and blood thinners were injected into my vein, aside from all the medicine I had to take orally.

I must admit, I began to feel some hesitation about going through the whole tedious process, but my fighting spirit prevailed.

Indeed, if there is one thing a COVID-19 patient should fear, it’s not the medication, the hospital, or its staff. It’s fear itself. There is uncertainty in being the afflicted one. Random thoughts, of death, of being cremated, would linger.

It was in those moments that made me reassess myself, and I reflected on my identity after a lifelong career in journalism. I decided to write about my experience as a COVID-19 patient.

I realized, after all, that as a journalist, what was happening in front of me was something I simply could not ignore. I felt the same duty that has driven me for most of my career: I needed to inform the public.

Besides, I figured, not all journalists who get confined for COVID-19 survive to write about it.

A COVID-19 patient clad only in his diaper and covered with a bed sheet lies on a gurney as he undergoes dialysis treatment at the hospital. Nurses at the dialysis treatment unit of the hospital work 24/7 to accommodate all COVID-19 patients needing the treatment. Joe Galvez

“This is too much to bear,” a nurse confided to me one day, as she changed the breathable adhesive tapes of my IV needle. “This hospital can only accept this much, and our wards are full to bed capacity. I feel sorry for the people afflicted by the virus.”

I felt the same way. My sympathies are with doctors and nurses who work beyond their limits just to take care of too many patients, even more so watching them work up close.

Filipino healthcare workers deserve to be paid justly and rewarded with decent perks and benefits. Priority should be the pandemic hazard pay they well deserve.

Despite its condition, the hospital with all its doctors and nurses were doing a good job.

Nurses told me that the elderly were the most difficult to handle during treatment. I saw one elderly COVID-19 patient who had to be strapped to a gurney because he was deliriously squirming in pain while undergoing emergency dialysis.

“Ayoko na, parang awa n’yo na, gusto ko nang mamatay.” I don’t want it, have mercy, I just want to die. Those were the words coming out of his mouth.

Doctors (left) in hazmat suits check on a patient as another patient with an air bag attached to his face looks on from his hospital bed. Joe Galvez

“Survive the 14 days and you’re out of hell,” another patient in my room joked.

It was my fifth day in confinement, but nothing seemed to have changed. Things seemed the same as it was on my first and second day. I felt like a prisoner in a place where death lurks. It felt like a battle to stay sane.

There were also decisions to be made. I was offered treatment with the experimental drug remdesivir. It is only administered to COVID-19 patients if they sign a waiver giving their consent.

I did some research and found that the World Health Organization (WHO) has recently recommended against the use of the drug on COVID-19 patients. In the end, I declined it on the advice of my daughter, who is a nurse.

The author’s hospital bed, which was the best spot in the ward: clean and well-kept.

I was lucky to have the best spot in the ward: clean and well-kept. There was a non-stop air-conditioning unit, and windows for sunshine and a view of the outside world. I would watch the plants and trees swaying with the wind.

One morning it rained, and just looking at the drops through the glass gave me a feeling of healing. The window made me feel like I was not a prisoner after all.

I spent my time reading the book “Blood and Wine,” the story of Robert Capa. I shared the room with three other COVID-19 patients. I was starting to gain weight. I almost began to like it there.

There were two septuagenarians in our ward. One of them seemed to be in an advanced state of dementia. He refused to have his samples of his blood extracted. He also did not want to take his medicine. He wouldn’t even allow his blood pressure to be taken.

He’d walk around the room in diapers. He would often shout invectives at the good doctors and nurses who would check in on us, and he was hostile to anyone who tried to convince him to eat or take his medication. He seemed mad at the world.

He would urinate anywhere he wanted to in the room. He seemed like he was in a really sorry state.

I asked a nurse if they had isolation rooms where they could transfer my ward mate, who was becoming a problem not just for health workers, but also the other patients. The answer I got was negative.

A healthcare worker adjusts the oxygen level of a COVID-19 patient before transporting him for dialysis treatment. Despite the protective equipment, some of them still end up getting COVID-19. Joe Galvez

On my seventh day of confinement, I was awakened at 11 p.m. by two of my roommates, both elderly men, who were yelling heated words and bursts of profanity at each other.

The first man could no longer walk. He had been rendered too weak by the virus, and he had been bedridden since his first day in the hospital.

The second man could still walk, but would need to hold on to sturdy things to keep his balance for even a few steps.

Both men were in diapers. I wondered what would happen if the two came face-to-face. Would I see a clash of clenched fists and splattered feces?

Thankfully, they were separated by a bed occupied by another COVID-19 patient.

Still, the ruckus continued for 30 minutes until a nurse arrived to pacify the two.

I guessed what I witnessed was the effect of boredom. Of isolation. Imagine having no relatives allowed to visit them. I guess they just had to take out their anger and defiance at anyone.

COVID-19 indeed has taken its toll on many of its victims — not just physically and financially, but also emotionally and spiritually.

As I prepared to sleep again, I began to wonder: What was going on in the heads of these warring old men?

But also: Would I cave in?

In my boredom amid the 14-day minimum quarantine, the thought of joining the melee seemed exciting. After all, I am a senior citizen too.

Then I remembered seeing a gurney earlier in the day, carrying an unconscious COVID-19 victim. I remembered taking a picture. It was a sad picture. Certainly a stark contrast to elderly men on the warpath.

To keep myself sane, I pulled my blanket up to my head, closed my eyes, and tried to sleep again.

A Mindray multi-parameter patient monitor keeps track of an intubated COVID-19 patient. Many people survive the ordeal but there are also many who do not. Joe Galvez

It was more than halfway into my confinement when I began calling on Jesus Christ for help. I said several prayers asking for a second chance in life. I knew deep inside that He heard my prayers. It really helped to communicate with Him.

Throughout my hospital stay, I kept hearing stories from nurses about death. People dying alone in their beds. Only after their families are notified will they be allowed to retrieve their bodies for the trip to the crematorium.

Afterwards, their families would receive their ashes. This is happening nationwide at hospitals, public or private, rich or poor.

That is one more thing eradicated by the virus: Filipino funerary traditions. No funeral wake, no funeral procession for the dead and their loved ones. We just burn the dead. It’s almost like we’ve gone back to pagan rituals.

Of course, I too thought about death. I would ask myself, “What if I don’t survive this virus.”

I began to think of so many media colleagues who have died during the pandemic, before my confinement. Journalists Bobby Capco, Melo Acuna, Nonoy Espina, and Cris Icban. Photojournalists Manny Goloyugo, Noli Yamsuan, Sonny Yabao, Ed Santiago, Ey Acasio, Emerito Antonio, Jun Aniceta, Jess Yuson, Jun Estrada, Allan and Tunying Penaredondo. All of them were my friends.

On September 5, about a week into my confinement, news of photographer Raymond Isaac’s death filled my Facebook feed. I thought it was unbelievable.

A few days later, on September 10, the death of another photographer friend due to COVID-19 also filled Facebook. Jay Directo, who had served as close-in photographer of former president Fidel V. Ramos, had passed away. The media community was in grief. I was in shock, because I was a COVID-19 patient too. Could death be imminent for me?

I began to think about the worst case scenario, the thought of leaving behind my happy family and my five beloved grandchildren. That was what made me sad the most.

It did not help that my second swab test showed that I was still positive for the virus.

“Who is going to take care of my family when I’m gone?” I asked myself.

An empty gurney is on standby to transfer a COVID-19 patient to the hospital isolation ward. Joe Galvez

The doctors and nurses who took care of me were very professional. In my confinement, I was bombarded with antibiotics and treatments, which made me feel rejuvenated, despite a surprise gout attack on my right foot.

I never had to be put on oxygen throughout my whole stay, but the doctor told me to keep my face mask on, even when sleeping.

Eventually, my dry cough went away.

I received the result of my third swab test on my 12th day of confinement. I was found positive again. That meant another five days in confinement. I was so dismayed I almost wanted to give up.

But as I reflected, I began to realize how my whole stay at the hospital had been an awakening. The experience showed me there was more to learn about life and living.

I also learned to overcome the fear of death. I realized that I would be at peace if it ever came to that point.

But it wasn’t all dire. My confinement gave me a better perspective of how people afflicted by the COVID-19 virus have gone on with their lives.

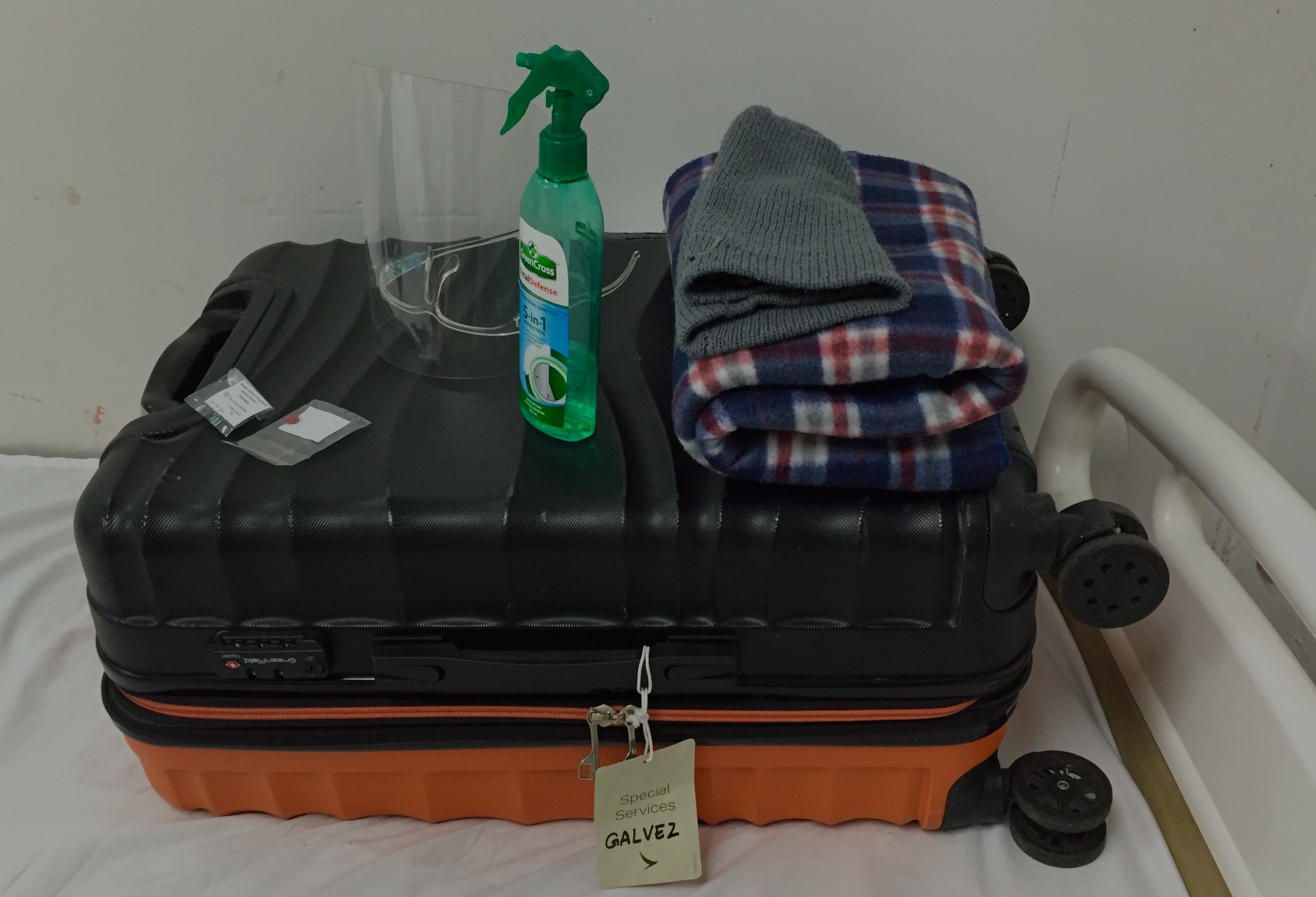

The author’s COVID-19 suitcase resting on top of his hospital bed for easy access 24/7. His wife prepared this suitcase which contained toiletry, clean clothes, a bedsheet, a book on Robert Capa, a powerbank, an extension cord, a lot of M&M’s, and his meds. The Netflix app on his phone was also a lifesaver — being a COVID-19 patient means being prepared to beat the boredom and loneliness, which could sometimes kill. Joe Galvez

On the 18th day of confinement, I finally tested negative. I got a clean bill of health from my doctor. I’ve never felt so happy and relieved.

“Laya ka na!” said the doctor. I am free.

I thanked the doctor and the nurses who took care of me, who kept me company and made me feel alive. They are amazing professionals.

I was finally released from the hospital. My grandchildren can finally visit me again at home.

Joe Galvez is an award-winning photojournalist. He retired as photo editor of GMA News Online in 2019.