The Philippines enters into an international loan agreement (with no collateral).

There are certainly many important topics to consider when discussing Philippine sovereign loans from China outside pure law and finance. But many of the concepts currently under debate are far simpler than tracking who is still alive in Game of Thrones. Here is a helpful explainer.

By OSCAR FRANKLIN TAN

April 5, 2019

Warning: Game of Thrones Season 1-7 spoilers ahead!

IMAGINE A GAME OF THRONES fanatic who mixes up Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister. Imagine him mouthing “You know nothing, Tyrion Lannister” and “A Stark always pay his debts” incessantly. Imagine him recounting Tyrion Lannister charging in at the Battle of the Bastards and Jon Snow rallying the troops at the Battle of Blackwater Bay.

Unfortunately, real world confusion regarding Philippine sovereign loans is as frustrating as Season 8 spoilers from a fanatic who mixes up Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister.

The most frustrating thing is that Philippine sovereign loan agreements are relatively simple compared to typical international loan agreements.

Many of the concepts under debate are far simpler than tracking who is still alive in Game of Thrones, concepts basic to first year finance lawyers and bankers. It might be easier to get Daenerys Targaryen’s phone number than hide a Red Wedding of a booby trap in a short loan agreement.

COLLATERALIZED VS. UNCOLLATERALIZED LOANS

First of all, mixing up “collateralized” and “uncollateralized” in finance is like mixing up Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister when standing beside Kit Harrington and Peter Dinklage.

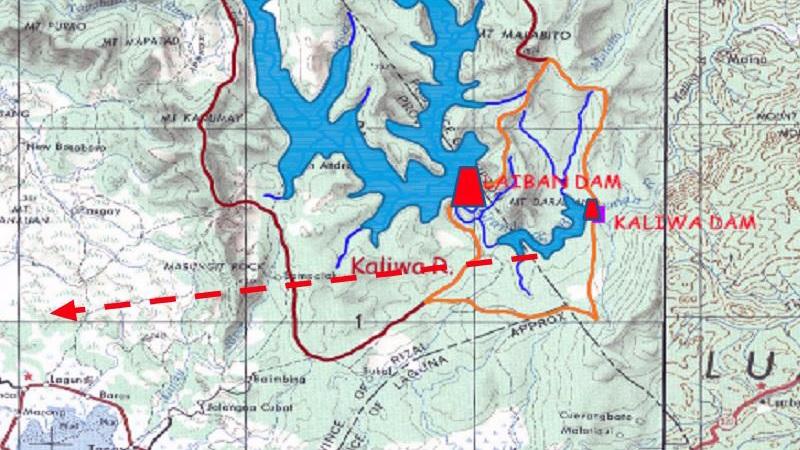

One can confirm that the US$62 million Chico River Pump Irrigation Loan (April 2018) and the US$211 million Kaliwa Dam Loan (November 2018), both from the Export-Import Bank of China, have no collateral. These relatively simple agreements (about 25 pages each, excluding annexes) can be downloaded from the Department of Finance website.

What is the difference between a “collateralized” and “uncollateralized” loan and why is it so basic that no first year finance lawyer or banker could possibly mix them up?

Collateral is familiar to us. If one does not pay a housing loan, the bank will foreclose on one’s house. If one does not pay an auto loan, the bank will repossess one’s car.

Simply, a loan has collateral when a borrower and a lender agree that if the loan is not paid, the lender may take specific property.

Because collateral radically changes a loan, it has to be very specifically written in — down to the specific title number of your land or the registration number of your car. Collateral is never automatic.

Try digging up your housing or auto loan. Look for the part that specifically refers to the specific title number of your land or the registration number of your car. If you signed a salary loan, look for the part allowing automatic deductions from your payroll bank account.

What happens if there is no collateral in the loan agreement?

Generally, if someone fails to repay a loan, the lender has to go to a judge. The judge must order the borrower to pay up.

If you signed an uncollateralized loan, such as a simple personal loan, and the bank suddenly takes your house because you failed to pay, the bank would be in big trouble and you would be the one suing the bank. The bank would be in such big trouble that no first year finance lawyer or banker would take someone’s house without collateral in the loan agreement.

Thus, if the lender wants to take the borrower’s house, the judge has to approve this, too.

Similarly, I cannot lend you P500 pesos and suddenly take your house when you forget to pay (unless you signed a loan agreement with collateral).

There is a big difference between being able to foreclose on a house in case of nonpayment — meaning, the bank is much more sure of being repaid — and having to go through the long process of suing a borrower in court. The difference is as big as the one between Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister.

COLLATERAL AND SOVEREIGN IMMUNITY

Collateral is such a basic and important point of a loan agreement that you should know it when you see it, just like you should know when a White Walker is standing in front of you, instead of Podrick Payne.

Collateral is as different from “sovereign immunity” as a White Walker is from Podrick Payne.

Article 8.1 of the US$211 million Kaliwa Dam agreement, the larger and more recent deal, reads:

“The Borrower hereby irrevocably waives any immunity on the grounds of sovereignty or otherwise for itself or its property in connection with any arbitration proceeding pursuant to Article 8.5 hereof or with the enforcement of any arbitral award pursuant thereto, except any other assets of the Borrower located within the territory of the Philippines to the extent is prohibited by the laws or public policies having force of law in the Republic of the Philippines, applicable and in effect at the signing date of this Agreement from waiving such immunity.”

This says “waives any immunity on the grounds of sovereignty,” not “grants collateral.” Again, there is a White Walker of a difference.

Waiver of sovereign immunity language is standard in any finance contract with a government (and typically put in non-government contracts anyway by careful lenders).

It is basic to first year finance lawyers and bankers. One can fact-check decades of Philippine sovereign bond documents at the US Securities and Exchange Commission website and the standard terms of lenders such as the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Why is a waiver of sovereign immunity standard and non-controversial in any finance contract with a government (and more so with a non-government)?

Think about how, in Game of Thrones, trial by combat (instead of a hearing) is not automatic, just as collateral is not automatic in any loan agreement. In fact, a lord may decline.

As hardcore Game of Thrones fans recall: Ramsay Bolton declined Jon Snow’s offer of trial by combat before the Battle of the Bastards (only to accept it later after he lost). Robb Stark declined Jamie Lannister’s offer of trial by combat after the Kingslayer was captured at the Battle of the Whispering Wood. Lysa Arryn declined Tyrion’s choice of Jamie as his champion in the trial at the Vale of Arryn. Even Tommen Baratheon abolished trial by combat throughout the Seven Kingdoms.

Like how the lords of Westeros have the right to trial by combat, governments have a real life right called “sovereign immunity.” Article XVI, Section 3 of the Philippine Constitution articulates it as: “The State may not be sued without its consent.”

This literally means what it says, and parallels how Tyrion could not be pulled into trial by combat until he agreed because he made his calculations. This makes sense because verdicts against the government would have to be paid out of taxpayer money that would be used to build schools and hospitals.

Obviously, one typical exception is that a government should not invoke sovereign immunity if it borrows money. Because of this special doctrine that applies only to governments, no lender would lend to a government without a clear waiver of sovereign immunity; otherwise, the lender could not go to court if the government refuses to pay — invoking what our own Supreme Court jokingly calls ‘the royal prerogative of dishonesty.’

What kind of lender would agree to a loan where it could not ask for repayment?

“The basic postulate enshrined in the constitution that ‘(t)he State may not be sued without its consent,’ reflects nothing less than a recognition of the sovereign character of the State and an express affirmation of the unwritten rule effectively insulating it from the jurisdiction of courts. It is based on the very essence of sovereignty. x x x [A] sovereign is exempt from suit, not because of any formal conception or obsolete theory, but on the logical and practical ground that there can be no legal right as against the authority that makes the law on which the right depends. True, the doctrine, not too infrequently, is derisively called ‘the royal prerogative of dishonesty’ because it grants the state the prerogative to defeat any legitimate claim against it by simply invoking its nonsuability. We have had occasion to explain in its defense, however, that a continued adherence to the doctrine of non-suability cannot be deplored, for the loss of governmental efficiency and the obstacle to the performance of its multifarious functions would be far greater in severity than the inconvenience that may be caused private parties, if such fundamental principle is to be abandoned and the availability of judicial remedy is not to be accordingly restricted.”

TRIAL BY COMBAT ≠ AGREEING TO LOSE

But remember that when Tyrion agrees to trial by combat, it means he agrees to combat, not that he agrees to lose. There is obviously a big difference.

If a government agrees to the standard waiver of sovereign immunity in a loan agreement, it only agrees to answer for nonpayment before a tribunal (instead of refusing to go to any trial because of sovereign immunity). It certainly does not agree to be liable for any nonpayment even before the trial or to surrender all rights.

Most importantly, it is an impossible logical leap to read the standard waiver of sovereign immunity as adding collateral to an uncollateralized loan. This is as impossible as thinking Tyrion agrees to lose every time he agrees to trial by combat.

(Spoiler: Tyrion is still alive as of the end of Season 7.)

If one knows the meaning of sovereign immunity from the first year, first semester of law school, it is not possible to read “waives any immunity on the grounds of sovereignty” as adding collateral to a loan agreement.

Especially when the phantom collateral is not even named in the agreement!

WHAT CARPIO SAID

Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio recently opined that if the Philippines does not repay an international loan agreement, we might lose an international arbitration and be made to pay for an arbitral award with property such as natural gas resources in Reed Bank.

He added that the more international loan agreements the Philippines enters into with a particular lender (such as the Export-Import Bank of China), the more chances this lender has of taking our country to arbitration.

Senior Associate Justice Carpio is our country’s most senior jurist and universally acclaimed as our greatest legal luminary, towering intellectual giant, most ardent patriot and the best chief justice the Philippines never had. He is also my personal legal hero and idol.

But the problem with citing a larger than life luminary is that we sometimes cite him by reputation and skip the nuances of what he actually said.

Senior Associate Justice Carpio is no mere first year finance lawyer and obviously knows the difference between a collateralized and an uncollateralized loan. He is obviously not claiming that a mortgage over Reed Bank is written into the Kaliwa Dam and Chico River agreements because anyone can read the actual contract and not find this in there.

Senior Associate Justice Carpio described a more nuanced process — not something as absurd as collateral in an uncollateralized loan agreement — but some commentators have not thought this through and inadvertently misrepresent it.

To spell out the process Senior Associate Justice Carpio outlines:

The Philippines enters into an international loan agreement (with no collateral).

The Philippines fails to repay the loan (in the case of the Kaliwa Dam loan, worth US$211 million plus 2% interest per year).

The lender initiates arbitration against the Philippines (in the case of the Kaliwa Dam loan, in the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC), with legal issues decided under the laws of China).

If the Philippines loses the arbitration, an arbitral award against it will be issued.

Since most Philippine government assets are in the Philippines (not in Hong Kong, for example), the lender must take the arbitral award to a Philippine court for enforcement—including if the lender asks to take specific property such as Reed Bank as payment.

A Philippine judge may rule that the arbitral award should not be enforced or not in the manner the lender wants. For example, a judge may rule that it violates “public policy” (meaning the public policy of the Philippines, not the country of the lender) and that something like Reed Bank cannot be taken by the lender.

Thus, as is familiar to law students in an arbitration class, there are a few steps required to get from Point A to Point B.

Most importantly:

The Philippines has to fail to repay a loan.

A Philippine judge — applying Philippine law and Philippine public policy— must approve the lender’s taking of any assets due to nonpayment of the loan."

ENFORCEMENT BEYOND ARBITRATION

So to recap, can a foreign lender take Philippine assets? There are two caveats.

First, one needs to include the actual enforcement of an arbitral award in the Philippines, not just the arbitration itself, in any analysis. Lawyers are trained not to stop thinking at a verdict, but up to how they will enforce it (and not be left with an empty verdict).

If one completes analysis to enforcement — not just the arbitration itself — one will see the final safeguard, a Philippine judge applying Philippine law and Philippine public policy.

Although the Philippines may agree that a loan agreement will be governed by the law of the lender’s country (whether China, Japan or Korea) even though this is not “neutral,” because it is the lender lending the money and may justifiably insist on this point, one must remember that an arbitral award will have to be dealt with by a Philippine judge under Philippine law.

Second, this conclusion is true of any international loan, not those from any specific lender.

If I somehow lent the Philippine government US$1,000 and was not repaid, I could theoretically end up owning Malacañang Palace.

One must thus take the argument that a foreign lender can take Philippine assets with a grain of salt, in this context.

If you want the full legalese, refer to the Philippines’ Special Rules of Court on Alternative Dispute Resolution (A.M. No. 07-11-08-SC, September 1, 2009).

Rule 13 is entitled “Recognition and Enforcement of a Foreign Arbitral Award.”

Rule 13.1 reads: “Any party to a foreign arbitration may petition the court to recognize and enforce a foreign arbitral award.”

Rule 13.2 reads: “At any time after receipt of a foreign arbitral award, any party to arbitration may petition the proper [Philippine] Regional Trial Court to recognize and enforce such award.”

Rule 13.3 reads: “The petition to recognize and enforce a foreign arbitral award shall be filed, at the option of the petitioner, with the [Philippine] Regional Trial Court (a) where the assets to be attached or levied upon is located, (b) where the act to be enjoined is being performed, (c) in the principal place of business in the Philippines of any of the parties, (d) if any of the parties is an individual, where any of those individuals resides, or (e) in the National Capital Judicial Region.”

Rule 13.4 outlines the grounds for refusing to recognize and enforce a foreign arbitral award. The last ground in Rule 13.4(b)(ii) is: “The recognition or enforcement of the award [in the Philippines] would be contrary to public policy.”

DOLLARS AND YENS

Waiver of sovereign immunity is not the only concept garbled in recent commentary.

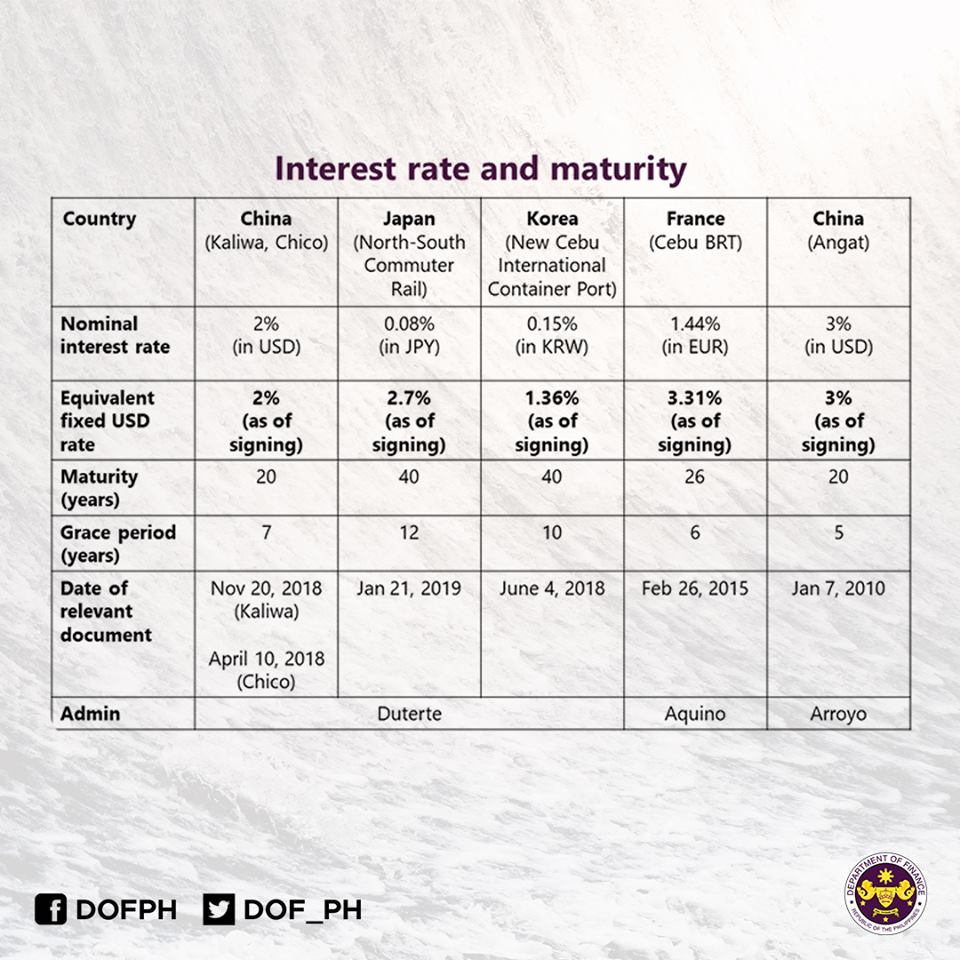

Some question why the Chico River and Kaliwa Dam loans (in US dollars) have a 2.0% per year interest rate when contracts with Japanese lenders (in Japanese yen) had interest rates from 0.25-0.75% per year interest rates.

The problem is that comparing US dollar and Japanese yen interest rates is the finance equivalent of mixing up Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister. This is like trying to use Philippine pesos to pay in New York.

A proper analysis adds the rate for converting (or the “swap” of) Japanese yen to US dollars. The Department of Finance actually posted these adjusted interest rates on its website, along with the loan agreements. They show the adjusted rates for various Japanese yen and Korean won loan agreements, which in terms of US dollars they compute at 1.36-2.88%.

The Department of Finance also showed the comparable US dollar rates from the international bond markets, which were 3.26-4.75%.

Finally, in January 2019, the Philippine government issued US$500 million of bonds in the international bond market, at 3.75% interest and repayable in 10 years (and with a waiver of sovereign immunity). For comparison, the US$62 million Chico River loan and the US$211 million Kaliwa Dam loan have 2.0% interest and are repayable in 20 years.

(Recall from housing loans that interest rates should be higher the longer the period one wants them fixed and not subject to increase.)

Finance concepts must be just as clear as legal concepts when debating international loan contracts. One cannot use Philippine pesos to pay in New York. One should not mix up Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister.

Finally, if one is debating what happens if the Philippines fails to pay sovereign loans, the broadest financial context is their actual amount. Secretary of Finance Carlos Dominguez has outlined that, at present, only 0.66% of Philippine debt is from Chinese lenders (compared to approximately 9% from Japan), and this ratio is targeted to increase to approximately 4.5% by 2022 or the end of Dominguez’ term.

To be sure, there are certainly many important topics here outside pure law and finance. How does flooding caused by new dams affect nearby communities and what are the tradeoffs? What are sustainable levels of national debt? How should we manage our foreign relations with each international lender?

Unfortunately, frustrating and pointless debate over extremely basic concepts such as the meaning of waiver of sovereign immunity and not comparing US dollar and Japanese yen interest rates has crowded out these discussions.

AN EMOTIONAL ISSUE

Sovereign debt is a more emotional topic in law and finance.

I once sat in a US international finance class on Argentina defaults and asked why at some point international lenders should not be made to bear the risk of not being repaid, because as a Filipino born during martial law, I was literally born having to pay for loans I never consented to. My classmates from Africa and Latin America echoed my sentiments.

Later, I found myself sitting in a conference room in Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance with the country’s most senior statistician, going through economic data for Indonesia’s international investors. She smiled and said, “You are Filipino! So you understand why we are so poor and why we keep borrowing money!”

But I recall her whenever I see the Jakarta international airport’s beautiful Terminal 3 or the brand new Jakarta MRT stations, opened in March 2019.

One hopes the millions of dollars we need to borrow each year slowly materializes into infrastructure and improves our quality of life.

During the Dengvaxia controversy, some Philippine lawyers were strongly criticized for spreading opinions on medicine and public health, even undermining public trust in vaccination programs, despite not being medical doctors.

In a similar spirit, given public hysteria over standard clauses in loan agreements, perhaps we should instead ask finance lawyers and bankers who have actually drafted sovereign debt contracts to explain them.

Perhaps we should only debate Season 8 spoilers with hardcore fans who can tell the difference between Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister.

Oscar Franklin Tan still believes that discussing legal principles in the Philippines is the epitome of pointless labor. He was chosen as one of the JCI Ten Outstanding Young Persons of the World (TOYP of the World) in 2017 and JCI Philippines The Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) in 2014. He received his Master of Laws from Harvard Law School, Bachelor of Laws from the University of the Philippines (where he chaired the Philippine Law Journal), and double-major in BS Management Engineering / AB Economics (Honors) from the Ateneo de Manila University.

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.