This is not the first time the prolific Catholic playwright, Floy Quintos, has taken on the subject of religion—in particular its more sacramental and/or “corporeal” aspects.

In Angry Christ, Quintos has found another propitious vehicle for his obviously unfinished quest to thematize the dissonance between religiosity and the more “mundane” sensibilities. As in his earlier plays, its premise revolves around the anguished relationship between the material and the ideal, the Spirit and the Flesh, with a concrete and specific object being made to bear the symbolic weight of the theatrical project.

Quintos engages in an extended theatrical description—more precisely, ekphrasis—of an actual historical work of art, made by a “minor” Filipino-American painter from the 1950s, Alfonso Angel Yangco Ossorio, whose family owned the Victorias sugar company in Negros Occidental. Naturalized and US-residing American citizens, Ossorio and his brother hardly ever lived in the Philippines for any extended period, and by all accounts he never really personally or at least passionately identified as a Filipino (let alone a Negrense).

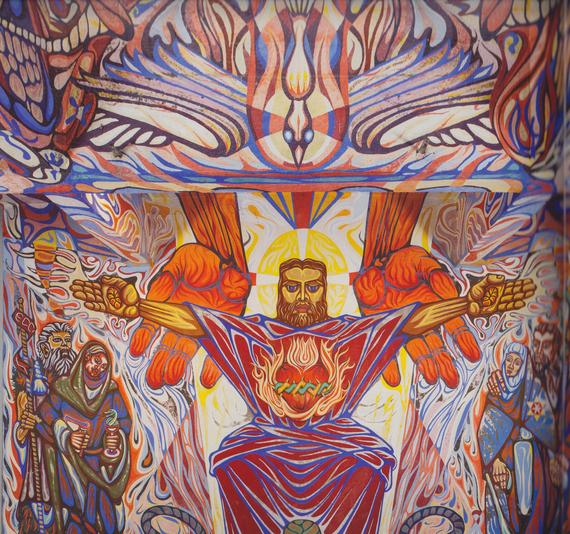

But Ossorio’s year-long visit in the 1950s did result in the modernist mural “The Last Judgment,” which incongruously adorns the chapel that his family had built for their plantation workers (sakadas) at the site of their hacienda's sugar mill.

For Quintos at least, this is enough reason to use his story as an occasion for yet another theatrical exploration into the fraught questions of spirituality and embodiment.

Ossorio proves additionally more intriguing because he was both Catholic and unapologetically gay, and going by the existing (albeit scant) documents he arguably inwardly suffered because of this fact. His subjectivity was unlike that of most Filipinos of his own time, thoroughly Westernized, educated in the urbane and cosmopolitan manners of First-World modernity, and therefore in an important sense self-aware (particularly in a sexual way) as he was. To all intents and purposes, Ossorio was a fully formed homosexual subject, and identified as such; he could only have (to some extent or other) suffered accordingly, in the sexologically conscious and sadly homophobic America of his time.

Local Philippine cultures, however, had no native categories for sexual orientation—especially where it impertinently pertains to the gender of one’s sexual object choice—although they did profess native gender terms (lalake, babae, binabae, bayot, bantut, agui, binalake, etc.), which did presuppose some kind of “male/female” norm. Furthermore, a century of literacy and sexologization has not wiped out our cultures’ customary understandings of (gendered) identity.

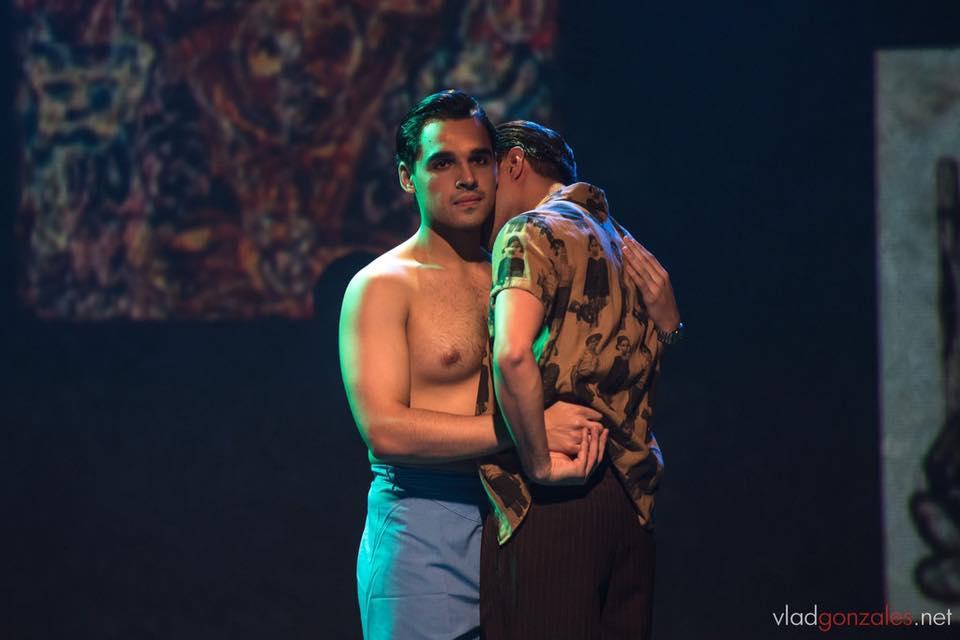

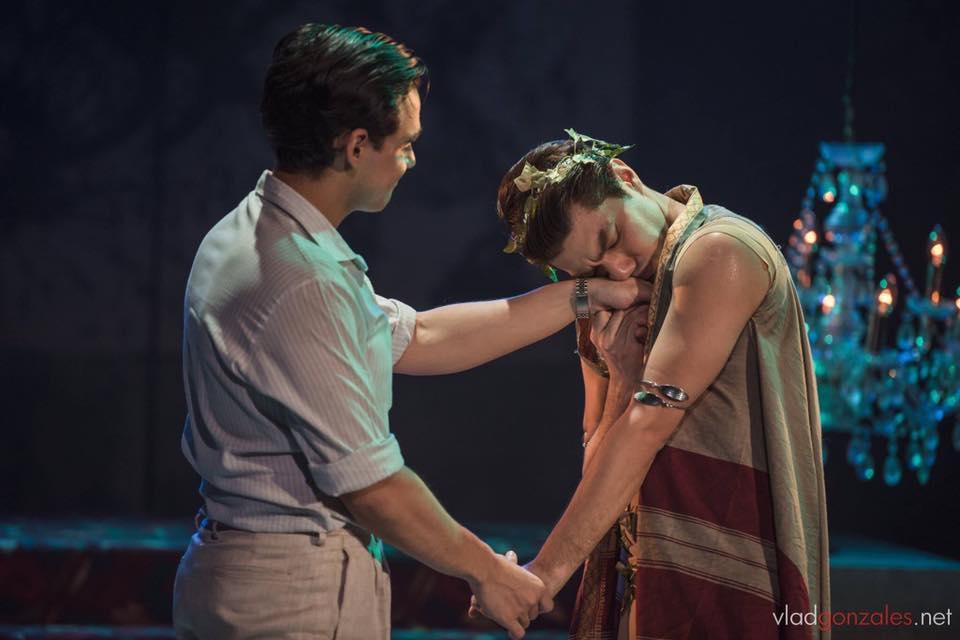

This is the cultural context within which Ossorio experienced his “homecoming” in the 1950s, and Quintos alludes to it briefly but acutely when he shows him flirting with Anselmo, the fictitious ward and “palangga” (beloved) who functions as a crucial plot device in this creative dramatization, and in a different scene cruising and presumably having mindless and contractual sex with a perfectly ordinary local man (hyperbolically enough, a bloodied Lenten flagellant).

We can only imagine the sense of alienation—possibly envy, regret, or perhaps even anger—this affluent, racially mixed, gay, culturally cloven, and diasporic character feels, all too keenly aware as he is of how “different” he is from these impoverished, outwardly Catholic but strangely morally unbridled people, who are not only from a life that is inexorably distant from his own, but who also routinely “profess” in one way and act or behave in another (and yet, unlike him, appear to suffer little or no shame or guilt in the process).

Unlike these orally and provisionally minded people, Ossorio in all his high-minded literacy and education could only live his life categorically, as his list of “necessities”—the difficult and obdurate realities that have conditioned both his social existence and his artistry, and that Quintos aptly quotes at length in his script—all too clearly reveals.

Unlike Quintos’ strictly religious reading of the mural (and its maker’s life), this cultural hybridity may well be the more interesting frame within which to situate its subject—which is the metaphysical “last judgment,” after all.

The ability to judge, to arrive at a conviction about anything, is something that came more naturally to Ossorio and to individuals of his class, than to the sakadas, who wouldn’t—as against Quintos’ avowed claim—have been able to make such an easy determination of the worth or value of a painting such as this. This would have been so not only because the aesthetic schema within which these sugarcane planters could see it was not remotely present to them, but also because their being orally minded already predisposed them against abstraction and its categorical forms of judgment, per se.

In my opinion, by equating the mural’s meaning with his own presentist (admittedly erudite and sexually self-conscious) values, Quintos misattributes profound existential shame to Ossorio (who appeared to have finally had no trouble openly leading the kind of gracious and beauty-filled life that he wanted, in his palatial home in the U.S.), and proffers a universalist and humanist reading that elides the cultural specificities of this artist’s formation as an aesthetic and sexual subject on one hand, and of Negrense society on the other.

Quintos, of course, is perfectly within his rights as an artist to do this, inasmuch as this is his own fully realized and compelling theatrical ekphrasis, after all. Among other writerly pleasures, this task gave him free rein to put on the critic’s hat and openly indulge in a form of extended commentary that lauds art for its ability to cite itself and thereby promote its own continuance.

But I do think it’ll also be interesting and historically productive to speculate about the possibility that other than the “pious” motives that Quintos has so effectively and dramatically proposed in his play, Ossorio painted this mural for this church, and produced this particular work—supposedly, his magnum opus—in this particular setting, simply because he could (he was filthy rich, and could do what he wanted, and this chapel was his own family’s property, after all).

As with any artist, the judgment that would’ve mattered to him would of course have been the judgment of his peers back in the East Coast. By daring to do his own take on such a grand and fraught subject, and yet by not making this Orientalist, ponderously allegorical, religious, tradition-bound, and in a way “unmodernist” work available to the liberal artistic circles to which he aspired to fully belong—by rather painting it in a permanent location on a faraway island, in the country of his birth—if anything he must have consciously tried to avoid precisely the kind of categorical judgment that this harsh portrait (and the morally irredeemable feudal life that made it possible) itself betokened.

If Ossorio had any social commentary to make at all in this work, it may have precisely been in regard to an ulterior wish (yet to be documented) that the painting's downtrodden everyday audience could turn profoundly literate and judgmental, able to finally summon the kind of abstract and righteous indignation to wage the kind of social and political revolution that might finally redeem them from the perdition of their own historical lives.

It is, of course, highly doubtful that Ossorio could’ve entertained such a thought, one that would’ve betrayed both himself and his own class to an enormous extent: we need to remember that right after finishing this mural, he quickly returned to his high-living and unrepentantly patrician ways in East Hampton.

As a visually layered modernist text, the mural is entirely polyvalent, figuratively textural, and complex. True to the devotional spirit of his previous works, Quintos prefers to see this art work as the direct expression of its maker’s own moral questionings, with its architectural placement inside the chapel’s modernist structure functioning as its aesthetic coup de grace. As Quintos argues it—taking the cue from Ossorio himself—this is a strategic placement that incrementally enswathes and bathes the painting in the purity of daylight and therefore visually obliterates it from the perspective of the heaven-oriented and kneeling supplicant.

While this insight proves poetic and moving (especially as articulated and dramatically embodied by the beautiful Nelsito Gomez, whose acting cathartically crescendos from restraint, indecision, to fiery conviction, across the play’s asymmetrical acts), this linear reading arguably also reduces Ossorio’s aesthetics to a simplistic representational mode that may not be apparent in the entirety of his oeuvre. On the other hand, it possibly limits the referential significance of this particular figurative enterprise, by wishfully ascribing to its maker a social conscience—or even just a social consciousness—that isn’t necessarily borne out by the available bits of documentary evidence.

The visage of this particular “Doomsday Lord” has been, after all, described as “angry” by onlookers, and this brings to mind the possibility that instead of a class critique, this mural may well be the expression of something entirely different, too—something diametrically opposed to Quintos’ well-meaning and benevolent interpretation, even.

After all, what it is is an imposing work of religious art that’s been strategically and theatrically placed inside the landlord’s chapel, and as such it may very well aim to instill the virtue of submission and moral dread in the believer, who also happens to be an indentured laborer in the landlord’s plantation. Admittedly, this is an easier and more commonsensical reading to make, given the available material, but the point, I suppose, is that crass and unflattering as it is, it cannot be entirely dismissed, either.

Quintos is in his element as a writer of these kinds of plays, for he obviously has deep affectional investments in the paradoxical subject of venality and religious symbology and/or iconography—something he shares, in a comparable measure, with Dexter Martinez Santos, who has directed his most successful recent works, and who reveals himself as being just as effective in this quieter, more subdued, and less kinetic production.

It may be relevant to state, in this regard, that in their personal lives both Quintos and Santos are santeros or camareros—collectors and caretakers of life-size religious statues, whose place in Catholic art and ritual is entirely compatible with this religious system’s incarnational theology. Theater as art is just as incarnational, after all: it traffics in the twinned anguish and bliss of corporeality—humanity’s paradoxical truth as both body and mind, matter and spirit. Theater may even be superior to the other arts, in this regard, inasmuch as it is uniquely and superlatively mimetic: not only does it represent life; theater actually presents it, onstage, by literally embodying its themes in the durational movement of its living actors, who inhabit bounded modicums of dramatic space and time.

Still and all, Angry Christ is an entirely satisfying experience, buttressed by a technically proficient production and a mostly competent cast (other than Gomez, noteworthy performances were turned in at the gala show by Stella Cañete Mendoza and Kalil Almonte). Of course, its strength finally derives from the integrity of its makers’ vision, that bravely pursues a theology that aspires to transcend the dualisms of dogma and yearns into the mysterious radiance—the Oneness—in which even the temporal forms from which art borrows its consolations (and its beauties) must finally, irretrievably, be lost.

There is sadness in this “transcendental” vision, then, for it abstracts and immolates the lowliness of matter to the Spirit that must purify and ennoble it. This is a lament that Angry Christ also registers somewhat, as light sheds its material guise at play’s end, and the visualized mural suffuses, diffuses, and ultimately vanishes from the funereally naked stage.

Being a finite gesture toward the infinite, art is finally nothing if not a sarcophagus—a figure that gets alluded to early in the play. Like the mythology it aspires to become, what art can only offer us—at the same time that it reels our vision inward and pitches it upward—are the fickle images and forms of our own dear and fugitive lives.

After all is said and done, metaphors are nothing if not empty vessels. Their referents—what they aspire to embody and contain—must live elsewhere. — BM, GMA News

Angry Christ is performed at the Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater, UP Diliman, until May 14. Go here for schedules and and ticket information.