Author Miguel Syjuco on Pinoy machismo, kabaduyan, and his new novel, 'I Was the President's Mistress!!'

Is there anything more meta than Vita Nova, a minor character from Miguel Syjuco’s critically acclaimed debut novel "Ilustrado," creating a “fanshrine” website for the author?

After 12 years, the starlet returns in Syjuco’s second novel "I Was the President’s Mistress!! (IWTPM!!)" this time as an election candidate with a platform “centered on education…so that we can all learn how the system works and how to organize ourselves in it, to fix it.”

In an exclusive interview with GMA News Online, the Montreal-based Filipino writer reveals how he finally fulfilled Vita Nova’s wish to ghostwrite her autobiography. Or not.

Below is the interview, which has been edited to reflect editorial policy.

Why did you focus on the life story of Vita Nova in your second novel?

I embraced the challenge by inhabiting the most misunderstood and maligned character in "Ilustrado," the one about whom everyone was making up stories: the sex-positive starlet Vita Nova.

Those years I spent trying to do justice to her character, my own perspective and limitations as a male writer proved difficult to overcome.

I decided to instead acknowledge my limitations and to look critically at machismo, using my male characters to unpack, expose, and implicitly condemn the casual sexism and defiant misogyny, and justifications for such, that I’d observed growing up as a cis Filipino male.

Because Pinoy machismo was something I knew much about, in my own way. As a searching, unsure teen in Cebu and Manila in the '90s, it seemed that the worst thing anyone could call a young man was bayot or bakla — as if, even if it were true of you, being gay was actually something wrong.

At the time, though, I didn’t realize that and because I was slender, light skinned, artistic, and more shy than my friends — and relentlessly teased for it — I overcompensated. I spent years chasing chicks, mistreating girlfriends, being ostentatiously unfaithful, and posturing as a babaero — confusing all that for masculinity.

And that’s why "IWTPM!!" is still very much a male-focused book — but one intended to take on the responsibility of exploring the misguided masculinity I grew up around and spent my life actively participating in.

And because of my own lifelong mask, I presented Vita Nova as both bida and contrabida who takes on a mask of her own: the guise of men’s assumptions, which she uses to her advantage to defy those very expectations.

Vita presents herself as a male-fantasy, meant in my book as both critique and comeuppance for the kind of men like I’ve been and strive to no longer be.

With the popularity of teleseryes and movies in the Philippines that have mistresses as the protagonists, do you think the majority of the public have accepted having a mistress as the norm?

It’s interesting that you draw a connection between the fictions of the teleseryes and movies as influencing social norms, when it’s initially the social norms that influenced the stories of the teleseryes and movies.

That proves the relationship—the influence on each other—between life and art. By portraying mistresses in our movies and teleseryes without condemnation, that to me also proves a certain acceptance of them in our society.

But you’re right about the seeming double standard between genders, which speaks to Philippine machismo. Men can have extra-marital sex, mistresses, multiple families, children out of wedlock, and be proud of it. Whereas women are still expected to be Maria Claras — or given grief for trying to break out of that.

Not only is that evident in the disparity you mention in our popular storytelling, it’s particularly clear in our politics. Joseph Estrada, with his multiple women, was celebrated as the Pinoy version of the proverbial Everyman. Benigno Aquino III was seen as suspect for his bachelorhood. While Rodrigo Duterte makes jokes out of rape, infidelity, and misogyny, [he poked fun at Senator Leila de Lima, insisting she was on a sex tape.]

That’s just Philippine society, where a sex tape may well be a source of pride for a man, while that same sex tape for the woman would likely hinder her prospects in life.

And this is because our society — the history of humanity, in fact — has used sexuality as a weapon.

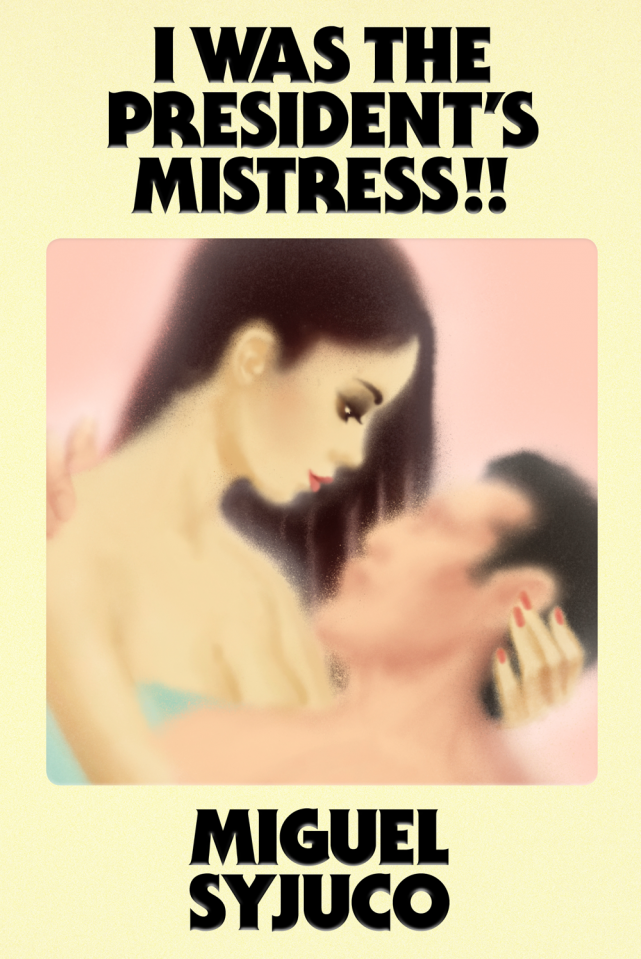

One of the book covers satirized cover designs of Tagalog romance pocketbooks, which imitated those of classic American romance novels. Should readers of your new novel expect it to vilify female fantasy and escapism? Or is it another metaphor to describe one aspect of Philippine society?

I think my novel is both critical and admiring of the power and pitfalls of fantasies, which is a theme that charts the history of the novel form, from Cervantes’s critique of the chivalric tale to Flaubert’s repudiation of the romantic novels that warped Madame Bovary’s conception of love.

Working in that novelistic tradition, I sought to nod towards the addicting, pulpy romance pocketbooks by using their very effective tropes to tell Vita’s story — but to dig deeper and to look more closely at related issues such as sexual mores, gender equality, patriarchy, participatory citizenship, media and disinformation, and our constitutional and universal human right to free speech.

Parody and satire, as literary strategies, are essentially subversive, and I hoped that "IWTPM!!" could help subvert, rather than vilify, the oversimplifactions we often see regarding sexuality, power, and truth.

But to me, the cover and design, and to a large sense the literary aesthetic, of "IWTPM!!" really speaks to one of the novel’s major themes: baduy.

I’m obsessed with baduy’s slipperiness and subjectivity, its shifting individual and communal judgments, its aesthetic intricacies that too often gets simplified for easy rejection, and how it is, to me, a defining characteristic of being Pinoy.

How did your involvement in the Resilience Fund, a project by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime to empower communities most threatened by criminality, influence your process in writing or revising "IWTPM!!"?

My work in civil society has profoundly influenced my writing. It started with my journalism work, when I decided to see and hear for myself what was happening in Manila’s most vulnerable communities under Duterte.

I went to crime scenes, attended wakes of EJK victims, interviewed politicians and human rights lawyers and police generals, went to rehab facilities and learned about the drug problem from actual professionals who are actively on the ground fighting it.

I’d seen too many Pinoy bloggers, in like the Netherlands or Singapore, spinning their opinions as truths and I decided that the responsible thing for me to do as a writer and citizen was to ensure that my opinions were informed by the realities of what was actually happening in our country.

Instead of interpreting evidence based on my opinions, I let my opinions be based on actual evidence.

Eventually, that work as a citizen-journalist led to my appointment to the advisory council of the Vienna-based Resilience Fund, which increased my opportunities to go see places in crisis and to speak to and learn from people who are building resilience in their communities against organized crime or abuse of power.

I’ve been able to meet and help support reformed gangsters in the shanty towns of South Africa, anti-drug organizers in Sierra Leone, community advocates fighting against enforced disappearances in Mexico, and so many others from around the world working against things like people smuggling, extortion, corruption, the illicit drug or wildlife trade, environmental exploitation, and all manner of urgent issues that are often under-addressed, overlooked, or even exacerbated by governments and societies.

I studied in earnest history’s surprisingly few novels—those works of fiction—that have had tangible effects on the world, such as shifting public opinion, improving government policy, ending slavery, launching revolutions, or changing how we all see the world. I wanted to know how someone sitting at a keyboard, at a desk, could write something that moved readers toward deliberate, effective action. This became one of my undergraduate courses at NYU Abu Dhabi, “Novels that Changed the World.”

Since the new novel is about the recorded interviews of a journalist, what are your thoughts on Filipino journalists today?

Journalists are the front-liners in this war on the truth being waged around the world, particularly in the Philippines now with the resurgence of the Marcoses...

As many democracies now slide further towards authoritarianism, the work of journalists is a lynchpin of the essential checks and balances meant to prevent our rulers from denying our human and civic rights.

What we’re seeing now in Europe makes this evident: it’s the work of journalists that shows us what’s happening in Ukraine, and it’s the silencing of journalists in Russia that’s kept so many people there fooled by the despot, Vladimir Putin.

In the age of social media, journalists are especially important. As private citizens, we all have the right to our privacy, but the actions of public servants must be examined in public — that’s the role journalists play: holding up to public scrutiny the relevant facts of whether our public leaders are fit to lead us.

What’s happening nowadays is that we citizens are voluntarily ceding our right to privacy (from what we ate for lunch, to where we went for vacation) while the public servants are fortifying their walls of privacy (from how they use taxpayer funds, to their medical fitness, to their statements of assets, liabilities, and net worth).

How do Filipino novels present the context of Philippine society and history to the world?

A novel is a theory — of itself, of the novel form, and of the world it seeks to portray. As a work of fiction, as mine is entirely, a novel strives to empower the reader, to give them the agency to decide for themselves what among the fiction resonates with life’s larger truths. That’s what makes the novel as fiction the opposite of the fictions of disinformation and fake-news, which consist of lies intended to disempower and therefore control us. Both are storytelling but with vast differences.

Storytelling is the stuff of life, giving us our identity, our aspirations towards purpose, our understanding of the world. Stories are powerful because they engage us personally, challenging us to consider context and to have sympathy for characters as representations of the humanity to which we belong. Stories are windows, as well as mirrors, to ourselves, our society, and our place in it.

But novels, with their length and undisguised fictionality, still serve uniquely as the most intimate, immersive, entertaining form of storytelling, demanding that we readers consider deeply the truths of our history, our present day, and the future that the narrative asks us to imagine.

To me, Jose Rizal’s novels exemplify all that. They were banned by our Spanish colonizers not because they were fiction, but because they rang true. They were mocking, funny, elegant, enlightening, and presented the context (the past, present, and future) of Philippine society at the time in a way that the Spanish friars and colonial government couldn’t abide. We Filipinos could see, and still can see, ourselves in the conflicted, hopeful, or heroic characters—just as we could see, then and now, our corrupt rulers in the characters who were excessive, ridiculous, and abusive.

Syjuco explained that his two novels are part of a planned trilogy. As a novelist, his role “is to unpack the past, interrogate the present, and imagine the future.” Ilustrado was about the past, while IWTPM!! is about our fleeting present. The final book, he said, “will be about the future—and that future, for sure, will be about climate change, and our country’s questionable ability to navigate its seismic changes.” — LA, GMA News

"I Was The President's Mistress!!" hits the shelves in April, one month before the Philippine presidential election.