Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Art review: Pop! goes religion in Legaspi's 'Pop Idols' exhibit

Text and photos by KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

Raymond Legaspi’s “Pop Idols” seems superfluous and loud, even too playful for comfort. But there is a layer of seriousness to the bright-colored portraits here, a rationale behind the size and scope of each icon as portrayed on Legaspi’s canvases.

The story is simple: a set of seven portraits of popular icons, one local, six world renowned. They are larger-than-life, literally: rendered in obese forms, with round faces and big bellies, which make them unfamiliar to some extent. What Legaspi banks on is the collective memory about each idol, beyond just face and body, and towards a public persona created as a whole image: what they do, what they are known for, not just how they look.

It is upon this collective memory of a public image for each idol that the failure or success of each of the portraits in “Pop Idols” depends. And it can only be a hit and miss, inasmuch as collective memory is also necessarily about the questionable notion of a mass spectatorship that will know of these images to begin with, that will know of these icons by default.

"Kris (Idol Ng Bayan)" stands for excess more than most.

It’s in this sense that the image of Jimi Hendrix fails, as he is only made distinct by skin color and an Afro, a colorful headband, fingers doing some air guitar, a huge smile on his face. It could be any other African-American singer really. The same is true for the Kris Aquino portrait “Kris (Idol ng Bayan)” which could be any other crying celebrity in our shores, looking up to the sky, tears falling down her fat cheeks.

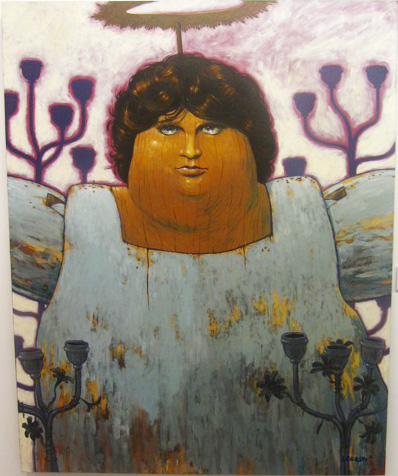

The Jim Morrison portrait “Light My Fire” is more successful if only because it captures the public image of Morrison looking straight into the camera with that dark stare, curly hair falling on his forehead, arms spread open in a welcome. The familiar stance of the public image is also what allows for the easy recognition of Bruce Lee in “Enter The Dragon” and Michael Jackson in the portrait with the same title, where the former is rendered wearing green and black, in his famous fighting stance, arms akimbo, body in movement, ready to pounce with puckered lips and fingers pointing. Michael Jackson meanwhile has one hand white-gloved, the other on crotch, and wears a hat over a white face and bright pink cheeks.

“We’re More Popular Than Jesus” is a portrait of the Beatles as four fat heads, distinct from each other by unique characteristics of glasses and beards, moustaches and hair. “Blessed Pope John Paul” meanwhile, like the Beatles, can only be as identifiable as it comes, with his classic pose with his pastoral staff, a smile on his face.

Across these portraits, Legaspi presumes a unity with the spectator: we must know of the same things, bound as we are by what is popular, what is in our database of memory and knowing, as spectators of cultural idols that are inescapable. But the task that Legaspi takes on is one that’s more than just this easy, happy rendering. What underlies it in fact is the bigger ideology that hovers over us as nation, no matter that we refuse it, no matter that we don’t believe.

"Enter The Dragon (Bruce Lee)" lends a layer of humor and absurdity to the idea of religiosity.

Because across these icons of our popular collective consciousness, is a symbol of Catholic religiosity as we know it: each of these idols are rendered with halos on their heads, some like angels, others like saints, across the board making each image a statement on adoration and belief and idolatry, religious and otherwise. And so Kris is rendered with a crown on her head, the pop drama queen layered with her notion of being Pinoy Catholic, questionable as that is. This same kind of absurdity is thus in the image of Bruce Lee, working as his icon does with a fighting stance, but with a halo on his head.

For some of the images, the layer of religion is nothing but redundant as with Pope John Paul, or just lost because the icon itself is unfamiliar as with Jimi Hendrix. For others though, it becomes more powerful.

Morrison’s image for example becomes layered with the fact of being drawn into those dark brooding eyes, his welcome arms easy to fall into, his icon rendered more powerful, his following more religious than we’d like to admit. Michael Jackson’s image doesn’t just have a halo on his head, but is shown as a full bodied Sto. Niño, one hand on crotch (or where the crotch would be under that full robe). It is difficult not to be reminded of the man-child as savior, but also of the man-child as a popular – and highly questionable – image for the pop icon, religiosity notwithstanding.

It’s in the Beatles portrait though that this layer of religiosity becomes meta-critical, because it banks on the spectator’s knowledge of what happened in the 1960s, when John Lennon himself said that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus and questioned the practice of Christianity then. Using that statement as title, the Beatles portrait pushes the notions of popularity and religiosity to its limit, where the four Beatles look straight at the spectator, with expressionless eyes but halos on their heads, like a statement of fact that we are not even being challenged into believing.

"We're More Popular Than Jesus (Paul, Ringo, John and George)" pushes the notion of the popular versus religion to its logical end.

What works for Legaspi’s “Pop Idols” one finds, is precisely this fact: there is a slow steady reveal of the jab it takes at religion, even as its statement on the creation of idols is already important. That it didn’t stop at the latter is what spells daring here: there is no looking at these images that will not mean a view of Catholicism as a practice filled with icons on the one hand, monsters on the other. The monster being more obvious for icons that use religion to justify their excesses, as is true for the one local icon here: Kris as drama queen also exists as the one who invokes Catholicism when convenient, that is, when it means asking for forgiveness or justifying her grand display of wealth.

Here the use of size to defamiliarize these pop idols also become symbolic: for what happens when the notion of being larger-than-life is rendered literally, what happens when these idols are made as large as possible, other than rendering them as strange? In light of those halos on their heads, in light of the religion that surrounds their creation as icons, the size of these idols become symbols of excess: the kind that is unforgivable because it is sinful.

In 'Light My Fire (Jim Morrison)', artist Raymond Legaspi renders the pop idol as the real religious icon he is.

That they exist of course in the figurative – none of these icons are as fat as they are in these portraits – is precisely the point. These idols are necessarily about excess, the idolatry that surrounds their existence premised on the breadth and scope of their images. That this can exist, and is fueled by a practice, akin to religion, if not Catholicism, is this exhibit’s critical stance.

"Christianity will go," he said. "It will vanish and shrink… We're more popular than Jesus now - I don't know which will go first, rock and roll or Christianity." – John Lennon (Cleave 2005)

If Legaspi’s “Pop Idols” is any indication, Christianity’s losing this battle against rock ‘n’ roll. And in our shores, given the industry of the popular that’s becoming more and more about the display of excess and fakery ala Kris, this can really only be especially true. –KG, GMA News

Raymond Legaspi’s “Pop Idols” ran at the Finale Art File, Makati City all of January 2012. John Lennon quote via: “The John Lennon I Knew” by Maureen Cleave, The Telegraph, 5 October 2005. Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular