Damning documentary on injustice comes home to Cinemalaya

Forty-two eyewitnesses placed Paco Larrañaga in Manila on July 16 and July 17, 1997, the day Marijoy and Jackie Chiong went missing in Cebu. Paco was a culinary student and a teenager, studying in Manila far from his Spanish-Cebuano family. Photographs showed him in Katipunan the night of July 16; his professors’ records showed his attendance at an exam the morning of July 17. But he was arrested, along with six other young men, for raping and murdering the Chiong sisters anyway. While Paco and his family waited patiently, then fearfully, for the justice system to regain its sanity, Paco was convicted. The judge refused to hear from all 42 witnesses. So the Larrañagas went to the Supreme Court as a last legal recourse. It elevated Paco’s sentence to death row. The chief of court was married, after all, to a relative of the Chiongs.  "Give Up Tomorrow" reveals, with damning, commanding clarity, the labyrinthine complicity of corrupt officials, sensationalist media coverage, and insidious family ties and personal favors that led to the conviction and imprisonment of Paco Larrañaga, Rowen Adlawen, Alberto Caño, Ariel Balansag, James Anthony Uy, James Andrew Uy, and Josman Aznar. Filmmakers Michael Collins and Marty Syjuco began research for the film in 2004. “We had no idea what we were doing,” they said. They read the manual for their camera on their first plane ride to Manila, and learned filmmaking as they went. Collins and Syjuco debuted "Give Up Tomorrow" at New York’s Tribeca Film Festival in 2011, where it earned the Audience Award and the Special Jury Prize. They’ve toured film festivals around the world since then. On July 22, "Give Up Tomorrow" screened for the first time in the country where Paco’s ordeal took place, at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Syjuco’s answer was simple, when an audience member asked him what took so long for the film to come home: “We’ve been waiting to be invited!” Cinemalaya had extended the first invitation. Much of "Give Up Tomorrow"’s footage is familiar to a Filipino audience raised on local media. The heavy-handed news anchors rendering their own verdicts too soon. The melodramatic, lurid, made-for-TV re-enactments. The sight of the MRT train and the Pasig River at dusk. But in the hushed and loud reactions of the film’s first Philippines audience, I could perceive the power of "Give Up Tomorrow"’s arrival in its home territory. “Talaga?” viewers muttered, when an investigator claimed to forget the name of a businessman who was under investigation for drug trafficking at the same time he employed the Chiong sisters’ father. “Panalo,” someone said sarcastically, when they saw that the President’s social secretary, a Chiong relative, had convinced Erap to speed along Paco’s prosecution as a personal favor. The audience laughed in disgust when they saw footage of the judge, napping. When the judge’s clerk read the men's guilty verdict aloud, many audience members in CCP put their hands over their faces. Some cursed out loud. Some wept.

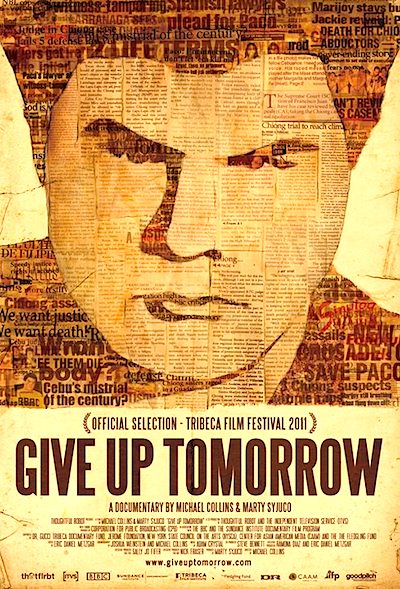

"Give Up Tomorrow" reveals, with damning, commanding clarity, the labyrinthine complicity of corrupt officials, sensationalist media coverage, and insidious family ties and personal favors that led to the conviction and imprisonment of Paco Larrañaga, Rowen Adlawen, Alberto Caño, Ariel Balansag, James Anthony Uy, James Andrew Uy, and Josman Aznar. Filmmakers Michael Collins and Marty Syjuco began research for the film in 2004. “We had no idea what we were doing,” they said. They read the manual for their camera on their first plane ride to Manila, and learned filmmaking as they went. Collins and Syjuco debuted "Give Up Tomorrow" at New York’s Tribeca Film Festival in 2011, where it earned the Audience Award and the Special Jury Prize. They’ve toured film festivals around the world since then. On July 22, "Give Up Tomorrow" screened for the first time in the country where Paco’s ordeal took place, at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Syjuco’s answer was simple, when an audience member asked him what took so long for the film to come home: “We’ve been waiting to be invited!” Cinemalaya had extended the first invitation. Much of "Give Up Tomorrow"’s footage is familiar to a Filipino audience raised on local media. The heavy-handed news anchors rendering their own verdicts too soon. The melodramatic, lurid, made-for-TV re-enactments. The sight of the MRT train and the Pasig River at dusk. But in the hushed and loud reactions of the film’s first Philippines audience, I could perceive the power of "Give Up Tomorrow"’s arrival in its home territory. “Talaga?” viewers muttered, when an investigator claimed to forget the name of a businessman who was under investigation for drug trafficking at the same time he employed the Chiong sisters’ father. “Panalo,” someone said sarcastically, when they saw that the President’s social secretary, a Chiong relative, had convinced Erap to speed along Paco’s prosecution as a personal favor. The audience laughed in disgust when they saw footage of the judge, napping. When the judge’s clerk read the men's guilty verdict aloud, many audience members in CCP put their hands over their faces. Some cursed out loud. Some wept.