Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

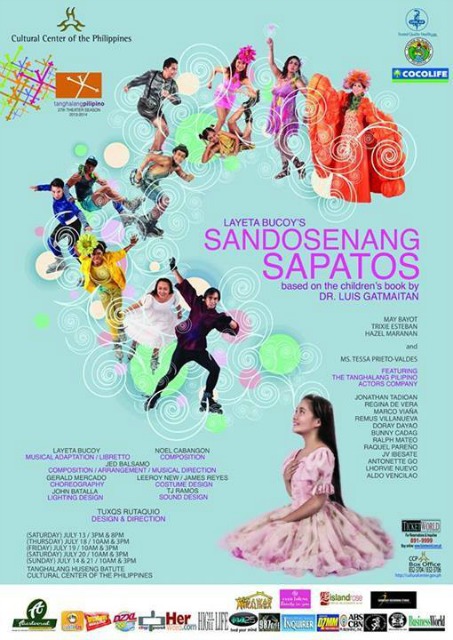

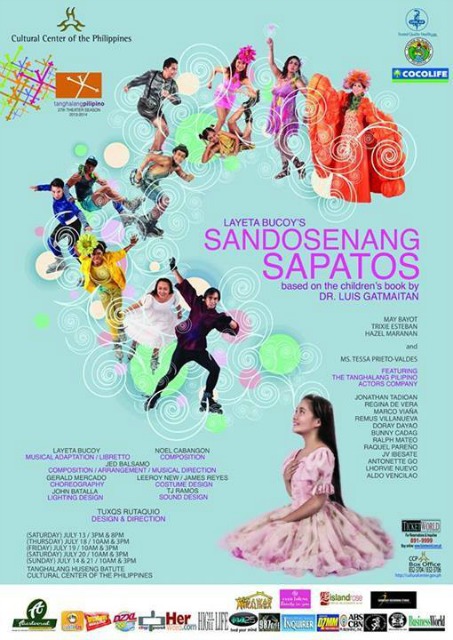

Theater review: Rupture in 'Sandosenang Sapatos'

By KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

It might be said that this story had everything going for it, including an original Pinoy children’s story that dares tackle the difficult subject of a child with no legs, and a father who makes shoes for the people he loves.

The easiest thing to do would’ve been to go all melodramatic on us with this one, throw us some heavy-handed motherhood statements about the tragedy of the sapatero in these times of development, the failing of a nation to allow for a 12-year-old girl to imagine herself normal no matter that she’s in a wheelchair, the inability of parenting as we know it to embrace the sadness of a child, too, because it is valid.

Instead what we are given in this: an adaptation of “Sandosenang Sapatos” that takes on the more difficult task of fantasy and dreaming, which it seamlessly ties to the narrative of want, the value of family, the question of happiness. Instead we are given a production that takes you by the heart, and will not let you go until that last note is sung.

Yes, this adaptation’s a musical, too. And in the end what it does is revel in a form of rupture, within the original children’s story, and given the original theater production as we know of it on these shores.

The fantastic as real

Susie (Trixie Esteban) is a girl about to turn 12 years old, and through the years she has survived the sadness over her missing legs by living in a dream world where shoes are people, and she’s a girl who can run and play like everybody else.

This is how the story begins, where Susie is wheeled onto the stage, and left to her own sadness and longing, her hopes and aspirations. We cannot but take to this little girl whose concerns revolve around the reality of being differently abled, who copes—if not survives—by shifting between the act of dreaming and engaging with the real.

The real being her father’s birthday, the one she is preparing for, the urgent task at hand being fulfilling her father’s original wish for her: that is, that Susie become a ballerina. That she was born with no legs of course is what makes her think herself dysfunctional, if not unable to make her father (Jonathan Tadioan) truly happy. Her sister (Regina de Vera) and mother (Mae Bayot) try to talk her out of it, to no avail.

Susie goes to the world of her dreams and wishes to finally make her father happy, by fulfilling his dreams for her. Unexpectedly, while in this world Susie has feet and is finally the child that she wishes to be in real life, it is far from the usual world of fantasy that would serve a little girl’s dreams on a silver platter.

Instead, she has to negotiate with these 11 people representing the 11 shoes her father would’ve given her for her birthday. She negotiates for the possibility of being normal for her father’s birthday, of being the little girl that he dreamt of having. Susie negotiates that this world of dreaming be brought the real, and she might dance like a ballerina for her father.

But this world’s fantasy is not one that delivers all of Susie’s desires. She does not only negotiate, she is also discouraged by her 11 playmates from thinking this is the only gift she can give her father. Instead they tell her to do the next best thing, which is give him a music box with a dancing ballerina. Instead they tell her: we cannot give you that.

It breaks this little girl’s heart, where within fantasy or the real, there is no making her father happy. There is no happiness, as such, for Susie with no feet.

The real takes over

In the process what “Sandosenang Sapatos” ruptures is the notion of fantasy as the place where everything might be had for the Pinoy child, and puts into question the children’s story that paints a picture of dreaming to be about perfection and the fulfillment of all desire.

Here, Susie is forced to beg and plead to meet the Diwata who might give her feet, who might speak to her about fulfilling her dream of dancing for her father. Here, she is faced with the great Diwata, and is only kindly reprimanded, told about what happiness means, what love for family, love for one’s father is about.

Here, it is the sadness in the real that will mean the fulfillment of Susie’s most ardent wish; it is only at that point that she realizes her discontent was the sadness of her father, too. There is a sense here of how Susie’s dreaming had brought to bear upon the real, where the fulfillment of her desires did not mean the fantastic being brought to reality, but the other way around.

In this sense, the realities of having missed the chance at happiness, of failing at being content with what one is able to achieve despite one’s condition, is the unsaid that is here. Susie had wished so much for the impossible that what was in front of her failed to make her happy. Never mind that this was the best her family could give her, never mind that this was a father coping as well with a daughter whose needs were bigger than anybody else in the family.

As such this adaptation also ruptures what is the intricate balance between the fantastic and the real that many children’s stories live off. Because here the real, from the reality of being differently abled to the real lessons about happiness and love and contentment, is where Susie evolves as a character. And it took a rupture within her real family life as well, for Susie’s character to turn around and find herself dancing with her father, finally.

One would think this the easiest story to tell. But that is only because it is easy to simplistically engage with Susie’s story and think her nothing but a child on a tantrum about some superficial unhappiness. For this adaptation though, none of this feels simple or easy, and that is because it also captures social class without having to push it down our throats, as it does speak of happiness and contentment not just for Susie, but for most of us who live with want.

Mostly too, “Sandosenang Sapatos” is able to push for the nuances of sadness and joy, family and need, childlike dreaming and real desire, because it is in the form of a musical. That is one form of rupture, too.

A libretto, a cast on wheels

What you realize about this text early in its unfolding is how critical it was that Susie be played by someone like Trixie Esteban, whose voice is perfectly angelic, as it also shifts to being defiant, if not almost spoiled. Susie wants something and demands that she get it: it is a child putting her foot down, and demanding more from the universe than she’s been given and allowed.

But also it is clear the moment you hear the lyrics to “Sa Panaginip Lang Ako Minamahal” that Susie’s discontent is far deeper than mere childish want, as it is about her sense that she is unable to make her father happy. The nuances of her discontent happen in song, in the manner in which this libretto’s been written, and how the compositions capture precisely the unspoken struggles in the real and the instability of joy in the fantastic, both of which refuse to give this little girl all that she wants.

It is fun when it needs to be, certainly. Where the 11 people that represent the 11 pairs of shoes Susie’s never gotten, or gotten to wear, get on that stage in rollerblades, gliding and jumping and dancing, as we imagine joy in our childlike fantasies to be. Here the freedom of feet on wheels become quiet counterpoint to the wheelchair that for Susie feels like nothing but entrapment. Here, the gift of an ensemble that learned to navigate that stage on those rollerblades, save for a few uncertain steps, is really quite a joy to watch.

I would’ve wished for far larger costumes for this fantasy, especially for the Diwata, if not ones as crazy as the red-haired man of velvet, or the one with a sunflower on his head. But one forgives that when one considers how much of the real is also here, and how the simplest of fantasy worlds is also all that this little girl could conjure.

This production, in fact, takes this kind of simplicity and runs with it, where the fantastic is easily subsumed into the real, and vice versa, without hesitation, and the rupture becomes our ability at engaging with this world as reality, full stop.

The music and lyrics of “Sandosenang Sapatos” will carry you from one end of this story to another, like a comfortable embrace that is about your own unraveling. It is because of the music that one is captured by this production, and it is what ruptures the idea of fantasy—if not the children’s story—as something that must carry us away with false hopes and dreams. Instead these songs are painfully real, intervening in the fantasy that is in most of this production.

But also it is reality that takes control of this production: sadness and discontent after all is at the heart of Susie’s character. It is difficult not to cry. Given Esteban, yes, but also given Jonathan Tadioan as the father, who can take that stage with only the kindest of a father’s smiles, as he might take on a stance that already speaks of defeat and sadness. By the time Tadioan sings “Tinatawid ng Pagmamahal” you cannot but be floored.

Yet the star of this show could only be the libretto, where we are reminded of how original music need not be complicated to be beautiful; how music, when well-written and composed, can capture what is at the core of the crisis in a text, in its characters, and in the process reveal its complexities. But too there is this: this adaptation proves that great productions are possible no matter how small, that there is daring and vision that is all about taking a text where it might not even imagine going.

That is, in “Sandosenang Sapatos” all you have is a small stage of ramps, precise lighting, thoughtful and careful direction—especially of Esteban and Tadioan—and the wonder of music and lyrics that will take you by the hand and allow you to live with this story, tears and all, which for all the time that it spends in a little girl’s fantasy, only really speaks to our humanity. That rupture is what makes this production infinitely valuable, if not absolutely relevant. —KG, GMA News

“Sandosenang Sapatos” was adapted for the stage by Layeta Bucoy from the original children’s story by Dr. Luis Gatmaitan. Bucoy did the libretto, with musical direction and compositions by Jed Caballero Balsamo and three songs by Noel Cabangon including “Sa Panaginip Lang Ako Minamahal” and “Tinatawid ng Pagmamahal.” This production was directed by Tuxqs Rutaquio, with lighting design by John Batalla. “Sandosenang Sapatos” opened Tanghalang Pilipino’s 27th theater season, and will run again in November of this year.

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular