Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

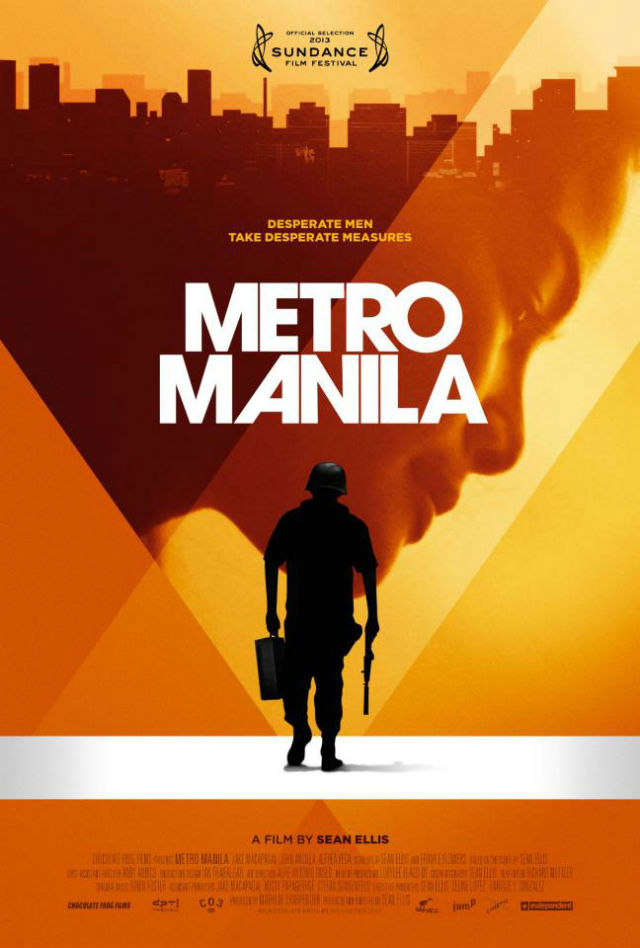

Movie review: Metro Manila as seen and transformed by foreign eyes

By VIDA CRUZ, GMA News

One thing I can say about Sean Ellis's “Metro Manila” is that it definitely knows how to hook viewers. Its opening scene features a figure partially obscured by a billowing sheet of purple silk sitting with its back to the audience, against the gray light of a dimming sky. Next thing you know, an old man is locking up a metallic sliding door, and turns around only to get shot in the face by a pudgy, balding man with a malevolent smile.

But we won't get to return that image and those characters for a long while. In fact, by the time we do, we'll have all but forgotten them.

"Metro Manila," which won the Prix du Public at this year's Sundance Film Festival, then follows the story of Oscar Ramirez (Jake Macapagal) and his family—a wife and two small daughters—as he uproots them from their native Banaue for Manila when they discover that their rice planting earnings won't last them until next season.

Life in Manila isn't easy, however, and the little family soon finds this out: Oscar moves from “job” to “job” as his family moves from house to house. The little family finds itself walking without rest for an evening when they quickly up and leave their spot on the sidewalk upon witnessing a woman's abduction. When they move to a makeshift house by a river in Tondo, his wife Mai (Althea Vega) manages to find a job as a dancer at a bar.

Oscar finally lands himself a job as a driver of an armored car, courtesy of Ong (John Arcilla), and for a while, it looks as if he has found redemption. But he soon learns that his troubles are just beginning.

"Metro Manila" won the Audience Award in the World Cinema Dramatic category at the Sundance Film Festival.

And all the while, in the mind, a question burns: will Oscar, still an honest farmer at heart, finally be driven to the damning desperation that tripped up so many of the other characters?

While I would say that the film's cinematography is superb, that Macapagal really earns your sympathy in his honest-to-the-point-of-naivete portrayal, that the use of the narrator voice-over truly carries the audience through some lingering, rather puzzling scenes (thus letting you know that you are not watching your typical Pinoy indie film), and that the decision of allowing the audience to pick up the foreshadowing elements in trickles throughout the film was pretty novel for a film set in the Philippines—with Filipino characters to boot—I do have some reservations.

For one thing, the pacing was uneven. We are treated to an enigma of an image and then a gunshot like a punch in the gut at the beginning, then we slow down as we watch scenes of the rice terraces during rainy season, a jeep breaking down in the middle of a deserted road at midday, and a spider crawling about its exceedingly fine web. It picks up a little as the Ramirez family moves into what looks to be the EDSA-Kamuning area and Oscar struggles with so many others just like him for a job.

And by the time we get around to Oscar as armored car driver and his buddy-buddy relationship with his senior Ong (mostly highlighted through long scenes of dialogue punctuated with very well-done flashbacks), the film is suddenly moving at a noir/thriller pace. It's as if Ellis first decided to be true to Philippine indie cinema sensibilities at the beginning then forgot himself and returned to a very Western aesthetic by the middle and the end.

There were also some bits of information that the characters dropped—or in some cases, were dropped on their heads like a bomb—that seemed to have no other purpose other than to keep the viewers at the edge of their seats. I note that Mai never told her husband about being pregnant with their third child, the existence of which she discovered while being examined by the doctor recommended by her would-be-pimp; nor does the pregnancy play a large part in the rest of the film.

The captions sometimes did not connote the actual meanings of what was said, but these did not really change the story.

But I always say that if something manages to hold your attention from beginning to end without allowing it to waver even for a moment, then it's had an impact on you. The impression that "Metro Manila" left on me was precisely like the aforementioned punch in the gut—it keeps you pinned and the sensation lasts for a while.

The film's sensibilities and the means through which its Filipino characters achieve their goals may be Western—and in a way, this defamiliarizes Manila and the Filipino psyche for the audience—but it is also precisely what gives you that "Aha!" moment when you get a glimpse of the core Filipino values bobbing in the wave of desperation in which the characters are close to drowning. Utang na loob, love of family, humility, and hard work are like beacons in unfamiliar territory, and they allow you a sort of coming home without ever having left your seat. They allow you to say to yourself, "Now, this is the Manila I know."

And kudos to the director for managing to portray a realistic picture of Philippine poverty minus all the gratuitous, Lino Brocka-esque poverty shots. That, ironically, is something fresh. — BM, GMA News

"Metro Manila" will premiere in cinemas on October 9.

More Videos

Most Popular