Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Remembering the wit and humor of Abdulmari Asia Imao

By VERONICA PULUMBARIT

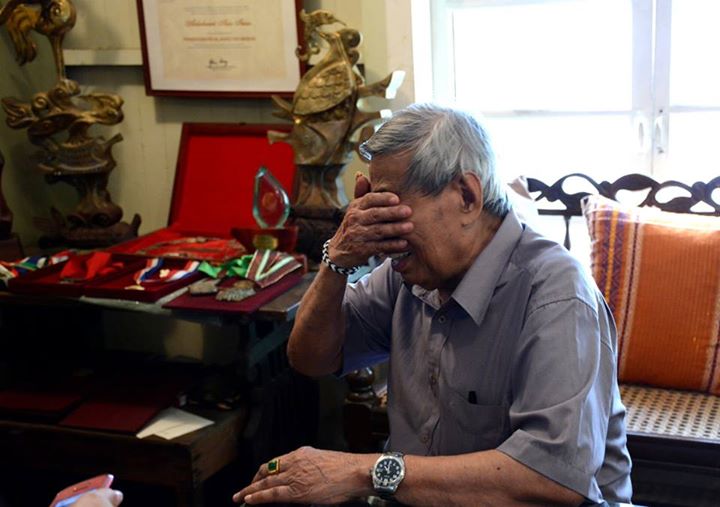

Mr. Imao was a very funny man. He kept laughing and cracking jokes throughout the interview that lasted almost three hours. Photos by Riz Pulumbarit

Imao was the father of my UP batchmate Toym Imao, a multi-awarded visual artist himself.

A few months ago, I was granted an exclusive interview with the elder Imao at his workshop in Marikina City.

Afraid that my knowledge about the arts was insufficient for a man like Imao, I dreaded the interview. What’s worse, we were about 30 minutes late as our car was sideswiped by a container truck on the way.

However, my fears vanished when we finally arrived at the workshop. The elder Imao was deeply concerned about the accident that befell us. He asked if we were okay and if we needed any assistance.

It was profoundly touching to hear such concern from an esteemed artist whose own health was already failing and who had to be assisted by two people as he walked.

Toym introduced me and my photographer husband Riz as his friends and the elder Imao welcomed us as such. Our conversation became more personal and we talked about everything from sarimanok to sarifish to World War II to conspiracy theories and even “chicks.” Yes, we talked about girls.

Reviewing my sound file from our conversation that lasted nearly three hours, I realized we hardly talked about the arts.

We would have talked more if Toym didn’t stop us, saying the sun was going down and we needed to wrap up our conversation if we wanted a tour of their expansive workshop.

From kargador to National Artist

Through Imao's work, the sarimanok became a popular symbol of the Philippines.

Through his works, the Muslim motifs such as the ukkil, the sarimanok, and the naga became popular not only in the Philippines but in other parts of the world as a symbol of the country.

Asked why his design motif recently changed from sarimanok to sarifish, he said, “Isa lang naman yan halos,” explaining that traditionally, the sarimanok is always carrying a fish in its mouth.

The sarifish also reminded the elder Imao of his younger days when he worked for five years as a fisherman in his hometown.

He felt there was no future for him there, an island separated from Sulu proper. “May ambisyon ako kaya umalis ako,” he said. He went to live with his aunt who owned a sari-sari store in another town.

“Nagtitinda ako ng popsicle, Coca-Cola, Pepsi Cola,” he said. “Nagkargador din ako sa pier, bente-singko isang biyahe.”

He used his earnings to watch movies, which became a lifelong hobby. (Toym said sometimes their dad would be unreachable by phone for hours and they would only learn later on that he was at the cinema.)

Around the time that he was doing odd jobs in Sulu, an art exhibit was mounted by the local government. It was Imao's first time to see large works of art.

The exhibit's curator noticed that he was going to the venue every day, observing the art carefully. He later learned that the young visitor had a talent for drawing and encouraged him to study in Manila.

Imao said he had hoped to receive a scholarship from Malacañang, but he did not get one. (At Imao's state necrological service, a family friend recalled how he collapsed while waiting in line at the Palace.)

A government official, however, offered to sponsor his studies in UP in exchange for doing odd jobs at his house such as washing the car or watering the plants.

Once in UP, he shone—and received several scholarships. And that was how Abdulmari Imao started on the road to becoming one of the country's most acclaimed artists.

Laughter

Toym Imao leads the author through his and his father's workshop.

About the three sculptures sitting prominently in his workshop, Imao said those were the first ones he made as a student. “Mga maintenance [staff] 'yan sa UP,” he said of the people who were his models for the sculptures.

About the painting of the beautiful young lady hanging above the sculptures, Imao said, “Yan si misis,” who had passed away a few years before him.

Explaining that his wife was one of his students when he briefly taught in college, Imao joked, “To sir with love kami.”

He became so in love with her that he married her even though he was a Muslim and she was a Catholic. He spoke of how he was really smitten by his wife as she was very beautiful.

However, his son Toym jokingly said, “Pero marami ang kasalanan kay mommy.”

Imao laughed but said to me quietly, almost in a whisper, that “mahilig ako sa chicks” before bursting into laughter again.

Then he pointed to his collection of medals, “Eto nga eh, marami yan dati kaso ipinamigay ko sa ibang chicks, pati sa abroad.” Imao had travelled, studied, and worked in different countries.

Before our conversation ended, I asked if he had any piece of advice for young people who were aspiring to be like him but he only said, “Masyadong maaga nag-aasawa ang mga bata ngayon. Hindi tuloy sila nakakaipon.”

Imao’s large-scale sculptures and monuments grace several sites around the country, including the Industry Brass Mural at the Philippine National Bank in San Fernando, La Union; the Mural Relief on Filmmaking at the Manila City Hall, and the Sulu Warriors at the Sulu Provincial Capitol.

Aside from the National Artist Award he received in 2006, he was also named one of the Ten Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) during the time of the late President Ferdinand Marcos. In fact, his son Toym was named after this award.

Goodbye, Mr. Imao! The Philippines will miss you. What an honor it is to have a fellow countryman like you. We will make sure that you are not forgotten. — BM, GMA News

Tags: abdulmariasiaimao, abdulmariimao

More Videos

Most Popular