ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

My mother’s notepads

By HOWIE SEVERINO, GMA News

+

Make this your preferred source to get more updates from this publisher on Google.

Part of a series on our moms—or about being a mom—for Mother's Day

For 28 years, my mother and I lived on different continents. For her last two, we were neighbors.

She had a massive stroke in late 2011 while living alone in her condo in Houston, Texas.

I flew there to be with her for three weeks, taking turns looking after her with my brother Kokoy, a teacher who was then her neighbor and rock of support.

From the fiercely independent woman who could do so many things with her hands, including sewing her own clothes, making the crispiest pata, and driving her Toyota Camry all over town, she became an invalid, barely able to move and speak.

But her mind remained sharp, which perhaps added to her misery as she was fully aware of what she could no longer do, like the long phone calls with her many siblings and friends. She was the only person I knew who could speak both Ilocano and Bisaya, not to mention Lao, the language of the country, Laos, where she and my father met when they were young development workers in 1959-1960.

She, my brother and I decided several months later that she would move back to the Philippines, where the suddenly dependent would have many more to lean on.

She insisted on having her own condo, and being in command of her own caregivers, her bank account and expenses, and even what she ate and wore every day. It was just her body that failed her, not the nimble mind that could still recall the names and dosages of all her medicines.

My priorities would change, some personal plans postponed or scrapped, as I adjusted my lifestyle and attention to the return of my mother's daily presence in my life.

But I welcomed my new responsibility as a chance to repay her for, well, everything.

Her stroke was a tragedy. But looking back, it also enabled those two years she spent with me. And I like to think it gave her joy too, as she would break into a wide smile every time I entered her bedroom to visit at the end of each day. Then the debriefing began, telling me gently what she liked and did not like on TV that day.

Bedridden, she watched GMA News TV all day long, absorbing the shows, including mine, and waiting for the replays of my old documentaries.

My mom was always my biggest fan. In Houston over the years, she would play for her guests and neighbors DVDs of even my oldest stories for The Probe Team. It was like the childhood photo albums had simply evolved.

In Manila, she got to watch me anchor the news every day, and in the evening would give me frank feedback about the interviews I did, as well as the occasionally ill-fitting suits I wore. All in the spirit of wanting me to improve, just like when I was 11 and she watched and listened to me sing soprano in the church choir every Sunday while dressed in a maroon robe.

When she completely lost her ability to speak, she would scrawl her commentary in a notepad with a right hand that barely functioned.

In those moments in her dimly lit room, she began to reveal little family secrets, like the real fate of the security blanket I had treasured into my adolescence. It did not get lost in a hotel during a vacation, but was discarded by my parents as it was unbecoming of a teen-to-be.

Now that my mom, Tati Gorospe Severino, is no longer with us, I regret not spending even more time with her, wallowing in her devotion and peppering her with queries about events I barely recall now. Like the young Constantino I saw one day in a May street parade. I was that small boy once, dressed in an itchy outfit sewn by my mom, the memory now almost zero-visibility in the fog of time. My mom with her unfading memory would have remembered that evening vividly.

The many notepads she filled in her last months are with me now, containing her end of the conversations she would have had if she could still speak. But today the notepads exist as gifts for posterity, available whenever I want to penetrate the fog or wallow in her devotion once more.

For 28 years, my mother and I lived on different continents. For her last two, we were neighbors.

She had a massive stroke in late 2011 while living alone in her condo in Houston, Texas.

I flew there to be with her for three weeks, taking turns looking after her with my brother Kokoy, a teacher who was then her neighbor and rock of support.

From the fiercely independent woman who could do so many things with her hands, including sewing her own clothes, making the crispiest pata, and driving her Toyota Camry all over town, she became an invalid, barely able to move and speak.

But her mind remained sharp, which perhaps added to her misery as she was fully aware of what she could no longer do, like the long phone calls with her many siblings and friends. She was the only person I knew who could speak both Ilocano and Bisaya, not to mention Lao, the language of the country, Laos, where she and my father met when they were young development workers in 1959-1960.

She, my brother and I decided several months later that she would move back to the Philippines, where the suddenly dependent would have many more to lean on.

She insisted on having her own condo, and being in command of her own caregivers, her bank account and expenses, and even what she ate and wore every day. It was just her body that failed her, not the nimble mind that could still recall the names and dosages of all her medicines.

My priorities would change, some personal plans postponed or scrapped, as I adjusted my lifestyle and attention to the return of my mother's daily presence in my life.

But I welcomed my new responsibility as a chance to repay her for, well, everything.

Her stroke was a tragedy. But looking back, it also enabled those two years she spent with me. And I like to think it gave her joy too, as she would break into a wide smile every time I entered her bedroom to visit at the end of each day. Then the debriefing began, telling me gently what she liked and did not like on TV that day.

Bedridden, she watched GMA News TV all day long, absorbing the shows, including mine, and waiting for the replays of my old documentaries.

My mom was always my biggest fan. In Houston over the years, she would play for her guests and neighbors DVDs of even my oldest stories for The Probe Team. It was like the childhood photo albums had simply evolved.

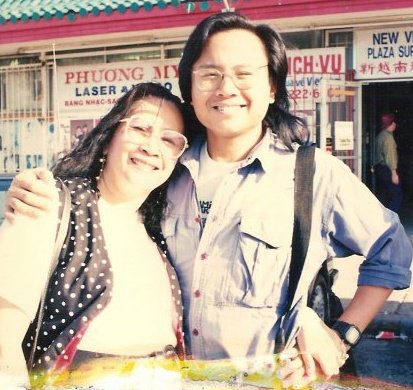

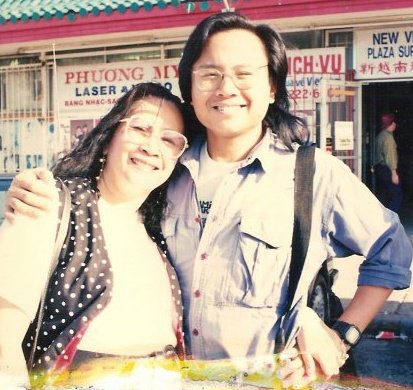

The author with his mom, Tati Gorospe Severino, in the early 1990s. Howie would see his mother only once or twice a year when she was living in the US. But after her stroke and she moved back to Manila, they saw each other almost every day. Photo by Kokoy Gorospe Severino

When she completely lost her ability to speak, she would scrawl her commentary in a notepad with a right hand that barely functioned.

In those moments in her dimly lit room, she began to reveal little family secrets, like the real fate of the security blanket I had treasured into my adolescence. It did not get lost in a hotel during a vacation, but was discarded by my parents as it was unbecoming of a teen-to-be.

Now that my mom, Tati Gorospe Severino, is no longer with us, I regret not spending even more time with her, wallowing in her devotion and peppering her with queries about events I barely recall now. Like the young Constantino I saw one day in a May street parade. I was that small boy once, dressed in an itchy outfit sewn by my mom, the memory now almost zero-visibility in the fog of time. My mom with her unfading memory would have remembered that evening vividly.

The many notepads she filled in her last months are with me now, containing her end of the conversations she would have had if she could still speak. But today the notepads exist as gifts for posterity, available whenever I want to penetrate the fog or wallow in her devotion once more.

Tags: mothersdaystories

More Videos

Most Popular