From Einstein's Universe to the Multiverse

Today, we know that the Universe is filled with galaxies, and our Galaxy, The Milky Way, is only one of many hundreds of billions. In turn, each galaxy is made up of billions to hundreds of billions of stars.

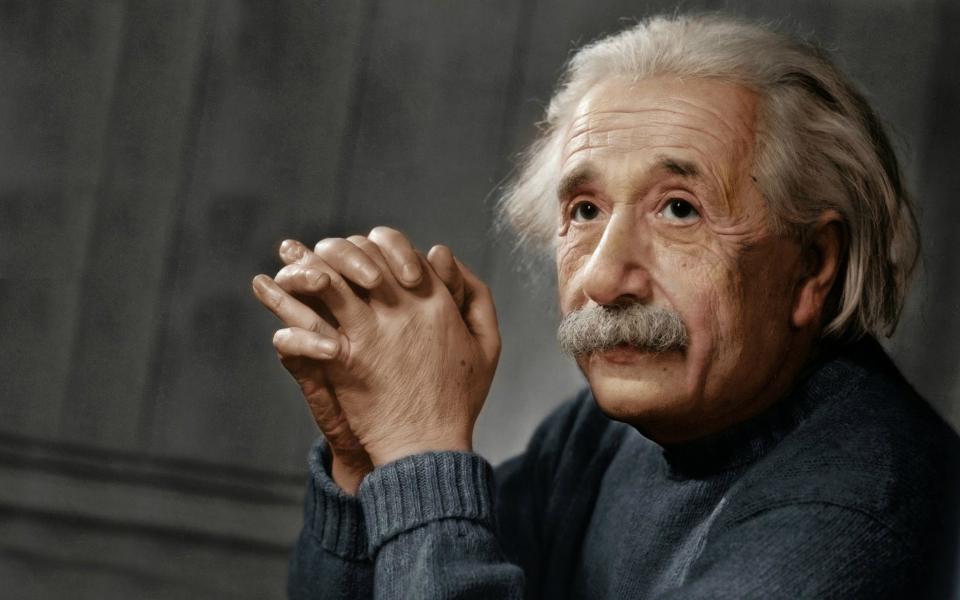

A century ago, in 1915, when Albert Einstein published his theory of general relativity, the picture of the universe was very different.

An early picture of collapse

Nebulae have long been observed in the sky, but they were thought to be gas clouds or groups of stars residing within the Milky Way. The Universe then was composed only of our Galaxy sitting alone, surrounded by an infinite, static, and eternal void.

In 1917, Einstein wrote a paper on the cosmological implications of his theory of general relativity. The equations naturally led to a universe that dramatically changes over time.

In particular, because gravity pulls everything together, the universe is expected to shrink and collapse.

To prevent this collapse, Einstein introduced a new term to his equations, the so-called cosmological constant, which acts like a repulsive force counteracting the attractive force of gravity.

The discovery of an expanding universe

But in the 1920's, astronomical observations of novae in the nearby Andromeda nebula, first by Heber Curtis, and more definitively by Edwin Hubble, showed that Andromeda is an “island universe” in itself, another galaxy just like our own.

Observing from the 100-inch Hooker telescope at Mt. Wilson Observatory in California, Hubble discovered more nearby galaxies, establishing our modern picture of a Universe filled with galaxies.

Moreover, in 1929, he discovered that almost all the galaxies he observed are moving away at great speeds, and that the farther away the galaxy is, the faster it is receding—a relation now known as the Hubble's law.

At that time, this was a puzzling discovery for which Hubble, himself, did not have a physical explanation.

The answer was a revelation: it was, in fact, space itself that was expanding! Just as described by solutions to Einstein's general theory of relativity as applied to Universe as a whole.

Einstein’s beautiful mistake

A Belgian priest and physicist named Georges Lemaitre had already published such a solution for an expanding universe in a French journal in 1927.

Einstein is said to have dismissed the result as mathematically beautiful but unphysical when he first heard of it. Subsequently, he praised it as an elegant solution, after the picture of the expanding universe has been well established in the early 1930's.

Contrary to popular notion, Einstein is human after all.

Today, the standard cosmological solution is also called the Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker metric, named after the four people who independently contributed to the result. This metric describes models of the universe that begin with a "Big Bang" and go on to expand, just as Hubble observed.

This expansion of space can either continue forever, or reach a turning point and reverse into a collapse, leading to a so-called "Big Crunch". The universe can be open or closed, depending on how much matter it contains.* If there is enough mass, gravity will eventually win.

At this point, the cosmological constant was out of the picture. And it has been called Einstein's "biggest blunder".

Yet even the man's so-called mistakes are brilliant.

The fate of the universe

The cosmological constant makes a comeback many, many years later with another surprising discovery from astronomy. In 1998, two independent projects studying supernovae in faraway galaxies found that the expansion of the Universe was not slowing down, but rather speeding up!**

We have an accelerating Universe, and Einstein's equations again need something like a cosmological constant to provide a repulsive force to counter gravity.

Today, this role is played by what we are calling “dark energy”, of which the simplest interpretation is it being the energy of space itself, or vacuum energy.

The good news is, a Universe with around 74% dark energy, 22% dark matter, and 4% normal matter, governed by general relativity, can reproduce all of our observations. This is our well-established standard model of cosmology. Everything works—and it works very, very well.

The bad news is that we do not have a plausible explanation for why the dark energy density is the value we find it to be—and in science, we want an explanation for everything. Calculations from quantum physics predict a vacuum energy that is 10120 times bigger than observed! That is a 1 followed by 120 zeros— this mismatch, also known as the vacuum catastrophe, is one of the biggest unsolved puzzles in all of science.

Perhaps, the solution awaits a full theory of quantum gravity.

A multitude of universes

Meanwhile, scientists are being led to an alternative, seemingly unscientific explanation: the idea of the multiverse. Just as the Galaxy is not the only one, but only one of many, many galaxies in our Universe, perhaps our Universe is not the only one, but only one of many universes. Ideas from string theory and inflationary cosmology naturally lead to this picture.

In the multiverse, universes will have different sets of fundamental constants, including the dark energy density. In some of the universes, this value will be so high, and accelerated expansion so fast, that there will not be enough time to form galaxies, planets, and therefore life.

In such a universe, there can be no observers, so such a universe cannot be observed.

Awaiting the next Einstein

This is the logic behind the so-called anthropic principle. In this picture, the fundamental constants we observe do not require any explanation. It was by random chance that we live in this universe and not another.

This non-explanation does not sit well with many scientists, but it is something some are desperate enough to consider at this point.

In other words, we need another Einstein—and we can only hope that she is already daydreaming her way to the solution, perhaps, in a nipa hut or under a coconut tree!

* Technically speaking, the universe can also be flat, with just the critical mass needed to keep it from collapsing.

**Both groups were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011 for their discovery.

Reina Reyes is a data scientist, astrophysicist, teacher, writer, and speaker. She has a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Princeton University and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics at The University of Chicago before returning to the Philippines. Currently, she is a part-time lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University and Rizal Technological University.

An earlier version of this essay was published and distributed on March 14, 2016, at the University of the Philippines National Institute of Physics Auditorium, in the souvenir program for “Sentenaryo ng Teoryang General Relativity”. This public symposium was held in celebration of Albert Einstein’s 137th birthday and the 100th anniversary of the publication of his general theory of relativity. Co-organized by the Institute with the National Academy of Science and Technology, the event featured talks by Dr. Perico Esguerra on Einstein’s life and work; Dr. Ian Vega on gravitational waves; and Dr. Reina Reyes on cosmology. This version is published with permission.