Blue crab mentality: Sustaining a billion-peso industry

On an otherwise unremarkable day, in the waters off the coastline of Carles, Iloilo, a vicious struggle for survival takes place.

It will take between four to six weeks for this batch of blue swimming crabs (Portunus pelagicus), commonly known as kasag or alimasag, to grow past their larval stage.

Until then, most of the miniscule swimmers (called zoeae) will fall prey to circumstances beyond their control, like becoming casualties of marine disturbances or supper for any of their numerous predators. Their naturally high mortality rate leaves only a small percentage of them to reach the seagrass beds and mangrove-rich nursing grounds where they can thrive.

Five more months will pass before each juvenile reaches the appropriate size for them to be considered “marketable.” Afterwards, a different struggle for survival will begin, as local fishermen cast their nets into the waters once more, crossing their fingers for a good catch.

Shell shock

Alimasag is one of the Philippines’ major export products. Statistics from the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) show that in 2015, the country exported 11,500 metric tons (worth around Php 5.1 billion) of alimasag, approximately 60% of which came from western Visayas. The following year, the species held the highest production value in marine municipal fishing, reaching a total of Php 2.87 billion.

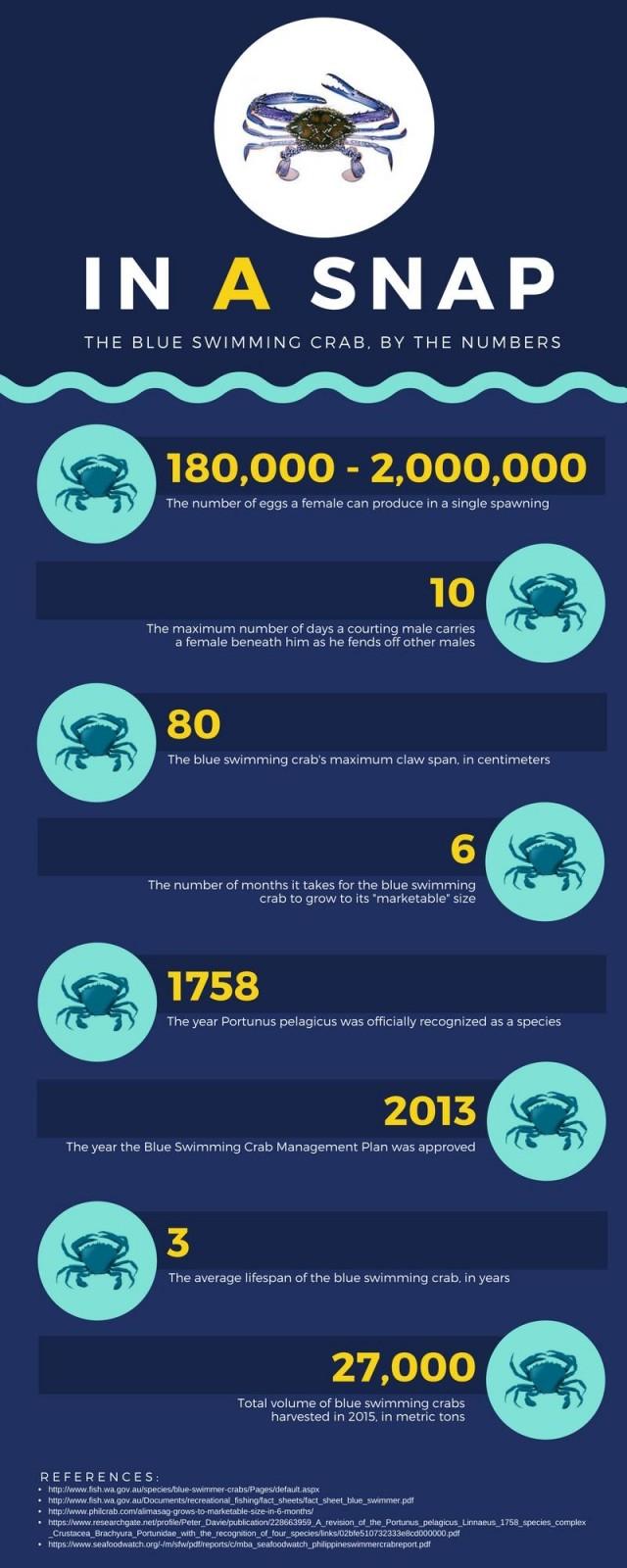

These numbers, however, hide a rather problematic reality. From catching 50,000 metric tons of alimasag in 1992, local fishermen were only able to catch 27,000 metric tons in 2015 — a 45% decline. Overfishing, habitat loss, illegal fishing, and the lack of a solid alimasag conservation plan over the past few years appear to be the biggest reasons behind the drop in alimasag harvest.

“There is a need to prevent further decline in crab abundance, so as not to impact negatively the livelihood of many fisherfolk,” shared Dr. Wilfredo Campos, a professor from the University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV), at a recent media brunch held at Hotel del Rio in Iloilo City.

Campos, who has been active in the field of marine conservation for 30 years, recently studied the settlement habits of alimasag in northeastern Panay with a team of researchers backed by the university. He and his colleagues identified key areas in the region that serve as major crab fishing grounds: Carles, Concepcion, and Banate.

Currently, Campos and his team are working on identifying where spawners and early-stage alimasag are most abundant— and perhaps more importantly, tracking the juvenile crabs’ journey to the fishing zones.

“We need to find out how the larvae, which are abundant further north, get to these fishing grounds,” explained Campos, who believes that water movement partially influences how the zoeae reach their preferred habitat.

Campos noted that observing other fishing grounds, like the ones in Capiz and Bohol, may also yield some useful insights.

Claw enforcement

Conserving the alimasag population will go a long way towards securing the livelihood of local fishermen, as well as the longevity of one of western Visayas’ major industries.

Campos believes that protecting the juveniles’ natural habitats and stricter enforcement of existing laws on alimasag fishing regulation should be prioritized. “In convincing local governments, it’s very difficult for them to implement [policies] where you’d have to reduce the source of livelihood,” Campos shared.

To the government’s credit, there are a number of initiatives in place intended to preserve the population and regulate the industry. For instance, there is a standing ban on catching egg-bearing crabs (known as “berried crabs”). Furthermore, fishermen are strongly discouraged from catching crabs that are smaller than 10.2 cm (4 in) in width.

_being_sold_at_a_wet_market_in_Iloilo_City_2017_12_28_10_15_14_0.jpg)

Campos also mentioned the Blue Swimming Crab Management Plan a set of regulatory measures for local alimasag fisheries. “There are many gaps [in the plan],” said Campos, “and our study tries to address some of these gaps.

A National R&D Program on Blue Swimming Crabs is also in place, a collaboration between the Department of Science and Technology’s Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources (DOST-PCAARRD), the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC), UPV, and the Mindanao State University-Tawi-Tawi College of Technology and Oceanography (MSU-TCTO). This program involves a number of initiatives for alimasag conservation, including nursery technology enhancements and broodstock management.

As Campos explained, habitat preservation serves a threefold purpose: to enhance the survival rate of young crabs, to maintain a healthy crab population, and to sustain livelihoods for the long term.

Seeing the bigger pincer

Interestingly, the fishermen themselves have begun to show openness towards adopting a more restrained approach to catching alimasag, if only to guarantee the continued longevity of their source of livelihood over the coming years.

“[The fishermen] have accepted that something needs to be done because hindi na ganoon kadami ang nahuhuli, e (because they no longer catch as much as they used to),” shared Campos.

“If we had been discouraged to talk to these fishermen 30 years ago, then wala sigurong nangyari (perhaps nothing would have happened).”

Ultimately, the key to a sustainable and profitable alimasag fishing industry is a change in both priorities and perspective — an entirely different definition of “crab mentality,” in a sense. — LA, GMA News