Filtered By: Scitech

SciTech

SPECIAL REPORT

The Aswang Diaspora: Why Philippine lower myths continue to endure

By BEA MONTENEGRO, GMA News

Creatures from Philippine lower mythology like the aswang, manananggal, or tikbalang are mainstays of contemporary popular culture. From movies to television to books, stories about them can be found not only locally but also abroad. Locally, the number of comic titles featuring them are on the rise.

But what is it about them that makes them so popular?

A brief history of unmentionable creatures

A brief history of unmentionable creatures

Cynthia Roxas and Joaquin Arevalo, Jr. suggested in their book A History of Komiks of the Philippines and Other Countries that some of the reasons that comics in general are so popular is because they portray aspects of the daily lives of Filipinos and because they tell stories about fantasy and magic. “And why is this thing about magic not alien to the Filipino thought? If we were to trace it from our past up to the present, the belief in magical powers such as the ‘anting-anting’, dwarfs and miracles is deeply rooted in the Filipino,” Roxas and Arevalo wrote. And indeed, in many parts of the country, many people still believe in stories about creatures of the night that eat fetuses or play tricks on lost travelers in the forest.

“I think they are popular because it is rooted in our culture. We first hear about these tales from our elders. Our ancestors actually believed and worshipped these mythological creatures,” said Mervin Malonzo, creator of Tabi Po. “I think a lot of readers are searching for this lost part of our collective identity as Filipinos. They want something that is truly ours and we are giving it to them.”

Interestingly, local supernatural creatures weren’t allowed to be depicted in comics for a time. The Kapisnan ng mga Publisista at mga Patnugot ng mga Komiks-magasin sa Pilipino (KPPKP), established in 1972 during Martial Law, released guidelines that needed to be followed by comic magazines. Said guidelines included a rule that called for toning down depictions of “horrifying creatures” and said, “Materials pertaining to fortune-telling, occultism, astrology, phrenology, palm-reading, numerology, mindreading, character reading, and the like are not allowed when presented for the purpose of fostering belief in them.”

Guidelines? What guidelines!?

Guidelines? What guidelines!?

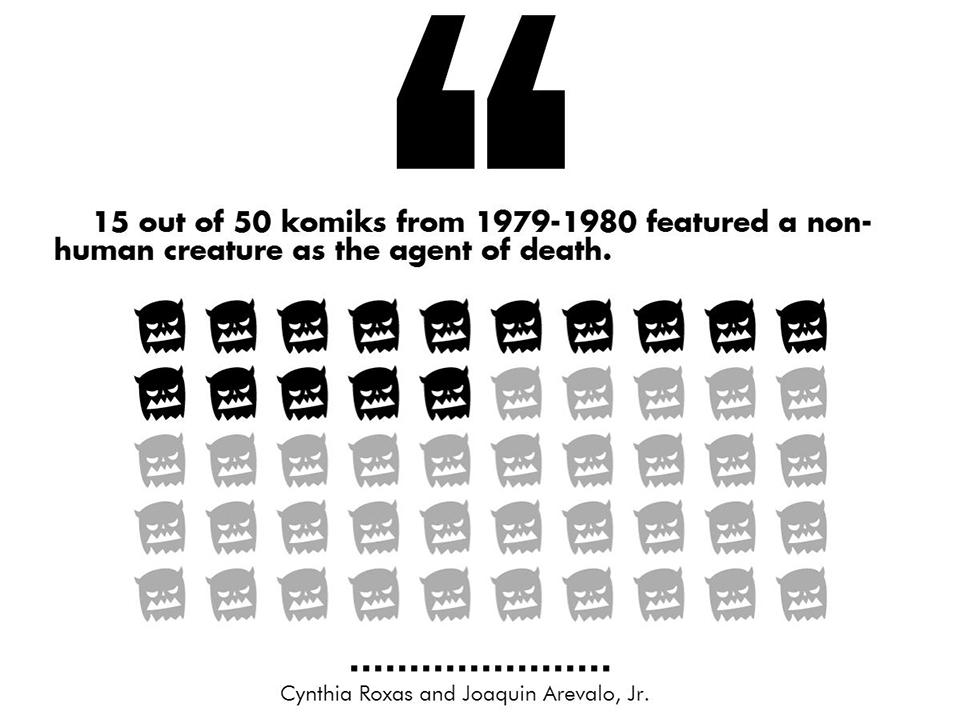

However, it seems comic writers and artists more or less ignored these guidelines—Roxas and Arevalo found that 15 out of the 50 comics from 1979-1980 included in their study “featured a non-human creature as the agent of death.” Instead of discouraging people from reading about these creatures, the ban may have made them even more popular by giving them the appeal of the forbidden.

Why do writers and artists decide to go back to supernatural beings for story source material? One reason is because no one’s writing the stories they want to share.

“[N]o one else was making stories about aswang in the city,” said Budjette Tan, writer of the Trese series. “In my case, I’ve always loved writing ghost stories and have always wanted to write a detective story. So I ended up creating Alexandra Trese as my occult investigator, as the reader’s guide into Manila’s supernatural underworld.”

Tan mentions that before him, there was Arnold Arre’s Mythology Class, parts of which take place in the Diliman campus of the University of the Philippines. Arre also shares a similar reasoning for the creation of Mythology Class; “Back in the late '90s I was looking for a comic book about Philippine mythology but I couldn't find any so I decided to make my own,” he said. “I wanted to make a story that would reintroduce our own myths and legends to comic book readers.”

Another possible reason is because creators want to take the opportunity to reimagine something they love. “[W]hatever specific creature I write into my stories, what draws me to Philippine folklore is a mixture between my genuine interest in our mythology (lower and otherwise) as well as a drive to see Filipinos and/or cultures from the Philippines represented in the type of genre stories that I know and love,” said Paolo Chikiamco, the writer behind the comic anthology Mythspace.

“In general, I think people enjoy seeing something of themselves—their beliefs, their culture, the stories they used to hear from their grandparents or peers—brought to life in a story, whatever media may be used to tell that story,” Chikiamco added.

“It's the most natural subject to draw, really,” said Kajo Baldisimo, Trese’s artist. “As young as three years old, these creatures were already a part of my and most of our generation's subconscious thanks to our parents and grandparents who have a great way of disciplining us by making us believe in these stories and these creatures.”

Malonzo shares that he created Tabi Po to make an aswang origin story, taking a new perspective on a familiar topic. “No one in recent memory have tried to explain their existence,” he said. “In their world aswangs have always existed, no questions asked. So I decided to make an origin story of the aswang and tell it in the perspective of the aswang himself.”

Aswang are in our DNA

Aswang are in our DNA

Perhaps it’s precisely this mix that makes these stories so endearing. The appeal of seeing something you’ve grown up with in a new way (changing from spoken stories to the visuals of comics) or being turned into something different but equally as fascinating (moving the stories from provinces to cities or even outer space). It may also serve as a way to negotiate our more historical identities with the realities of modern life, making sense of stories that come from our grandparents’ parents in the context of our current surroundings.

“It's in the DNA of every Filipino,” said Baldisimo.

“It’s one of the few things we can clearly say is very Pinoy, something that’s ours,” Tan said. “I think telling aswang stories is something we’ll always want to tell. There are so many variations on their story, depending on how tells the story. Someone will always have their own version to tell.”

Arre thinks that the revival of lower mythology in our stories is a “reflection” of the wider global scale of popular culture. “I’m attributing their resurgence in popularity as a reflection of what was happening abroad. There was an influx of fantasy movies this past decade,” he said, citing Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter as examples. “All of these stories explored magic, fantasy, and their respective country’s folklore. It was only natural that local authors would follow that route and look into our own mythology too.”

The aswang diaspora

Is there a market outside of the Philippines for our beloved creepy creatures? As mentioned earlier, supernatural beings from our lower mythology have already made their way into foreign media, and one can only assume that with the growth of their popularity in the country, their international popularity can only go up as well.

“I want that to happen more often,” Malonzo said. “I want aswangs, kapres, and tikbalangs to be as popular as Japan's ninjas and samurais.”

Budjette Tan, Mervin Malonzo, and Paolo Chikiamco are all part of Studio Salimbal, a local comics studio named after a ship “from Bukidnon mythology that can take people directly to heaven, without first needing to die.” Chikiamco also founded publishing imprint Rocket Kapre. The art for Mythspace: An Unfurling of Wings was drawn by Borg Sinaban and the art for Mythspace: Lift Off was drawn by Koi Carreon.

— TJD, GMA News

References:

Lent, J.A. (1998). Comic art in the Philippines. Philippine Studies, 46(2), 236-248.

Lent, J.A. (1999) Pulp demons: International dimensions of the postwar anti-comics campaign. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Roxas, C. & Arevalo, Jr., J. (1985) A history of komiks of the Philippines and other countries. R. Marcelino (Ed.). Manila: Islas Filipinas Publishing Co., Inc.

Tags: mythology, popculture

More Videos

Most Popular