ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Topstories

News

Water can't hold names of sponsors

BY JAKE SORIANO, GMA NEWS RESEARCH WITH THE GMA NEWS SPECIAL ASSIGNMENTS TEAM

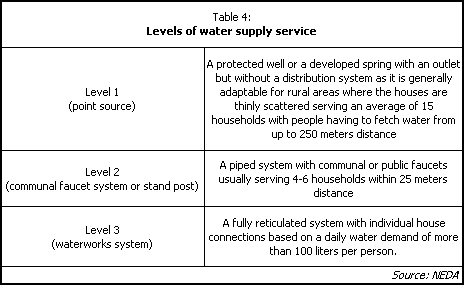

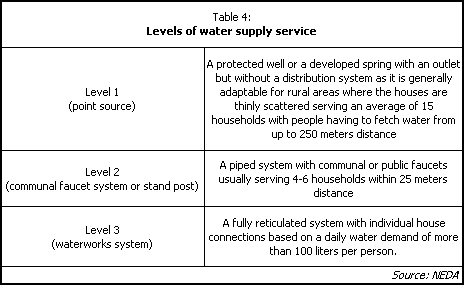

(Second of two parts) Experts say that among the three levels of water supply infrastructure, Level 1 sources are the least sustainable and the least safe.

(Link to the first part)

(Link to the first part)

"Actually ang policy ng national government ngayon, especially doon naka-stipulate sa Roadmap, parang as much as possible, wag na magi-implement ng Level 1, kasi ano nga sya prone to contamination, [The national government’s policy, stipulated in the roadmap, is to avoid implementing Level 1 projects as much as possible because these said projects are prone to contamination,]” explains Fe Banluta, project officer of the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) Water Supply and Sanitation Unit.

The Roadmap, released by the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) in 2010, identifies and seeks to address the problems of the water supply sector in the Philippines.

Robert Domingo, Chief Development Specialist of the Water Resources Division of NEDA says water supply structures should be at least Level 2 systems.

“We stress that water as a resource is not purely a social good,” Domingo explains. “It’s also an economic good.”

“Pag Level 1 kasi, [When you build Level 1 projects,] it’s hard to entice people to conserve the resource,” he says. “Hindi sya efficient use of the resource, [It’s not an efficient use of the resource.]”

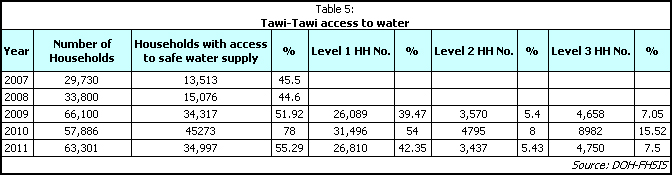

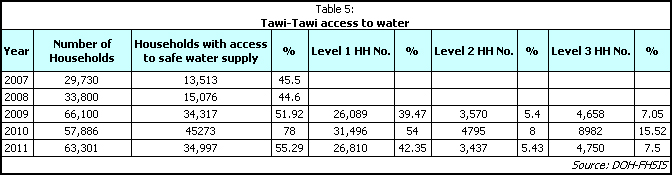

Through the years, the seesawing water access rates of Tawi-Tawi illustrates the problem of sustainability in the province’s water supply sources.

In 2008, the latest complete nationwide statistics available from the Department of Health Field Health Service Information System (DOH-FHSIS), less than half of Tawi-Tawi’s population had access to safe water.

The province’s 45.5 percent access in 2008 is the second worst in the Philippines after Lanao del Sur’s 39.7 percent (Table 1).

The following year, the Tawi-Tawi numbers improved, breaching the 50 percent mark, indicating that at least half of the population had access to safe water.

In 2010, the increase in access continued, this time with a massive jump—the percentage of households with access to safe water skyrocketed to 78 percent.

This rate meant Tawi-Tawi was well within the Philippines’ MDG target of 86.5 percent access to safe water by 2015 if the upward trend continues.

But the province’s water coverage, inflated by Level 1 sources, was short-lived. Numbers plummeted the following year: access to water Tawi-Tawi in last year’s data is back to 55 percent.

“Some localities don’t really have the capacity to maintain the system,” Domingo explains. “They get money to build up a system, yung hard infra like well or pipes, tapos wala silang [but they don’t have the] capacity to really operate the water system. So it only is sustainable for such a period lang. After that, wala na. [After that, it’s gone.]”

Water can’t hold names of sponsors

Yet in Tawi-Tawi, water supply projects are at the bottom of the list among pork barrel projects. (Table 3)

“There are literature na mababasa mo na if you compare yung ibang public utility sectors, parang lagging behind yung sa water, [There are literature available which suggest that if you compare spending on public utility sectors, water supply always lags behind,]” NEDA’s Domingo says.

“Probably because the implication na mas may dating yung ibang sector. Halimbawa, you build a road or a school building na pwede mong lagyan ng pangalan ng kung sino nagpagawa, [The implication seems to be that other utilities are more popular and better-received by the public. For example, government officials could put their names on roads or school buildings,]” he says.

“Subliminally, yung mga taong nakakatingin nun araw-araw, day-in day-out, they see the name, it gets stuck in their mind. Pero sa tubig, paligo mo lang, inumin mo, then what, [Maybe subliminally for the people who see these utilities with their official’s name everyday, it gets stuck in their mind. But the case is different for water projects. You use the water for bathing or drinking, and it’s gone,]” Domingo adds.

Imelda and Radgma, skilled in telling when rainwater is safe for drinking, are comfortable in the fact that as long as they and their families do not get sick, everything is good.

“People have been used to that source of water, maybe since, siguro since time immemorial. They have been getting water from that source,” says Dr. Sukarno Asri, Tawi-Tawi provincial health officer. “So to them ok na yung source of water [So they are content with drinking water from the rain,]” he adds.

But diarrhea and gastroenteritis remain the fourth leading cause of morbidity in the province.

“Fortunately, wala namang major outbreak of diarrhea cases sa Tawi-Tawi [Fortunately, there has not been major cases of diarrhea in Tawi-Tawi,]” says Asri. “But there are occasions na may mga increase sa cases of gastroenteritis which are sometimes related to contamination of water.”

Children are the most vulnerable. Of the 1,282 cases in Tawi-Tawi recorded by DOH FHSIS in 2011, 742 or six in ten, hit children below four years old.

Rep. Jaafar admits the urgency of the need of his constituents is not the only consideration in funding projects.

“Hindi mo naman pwede ibuhos lahat doon [water supple projects] kasi marami ka ring constituents, [You cannot really allocate on water supply projects alone. You have many constituents,]” he says. “Gumagawa ng listahan. Nagre-request ng project dito, project doon. [They send you lists of projects they want.]”

“We have to allocate as an elected official,” he explains. “Kahit sino pa man, dapat naman pagbigyan mo yung mga constituent mo para makabalik ka sa pwesto, di ba? [You have to please your constituents so you could return to office.]”

He says further that he picks his projects “according to priority.”

“Depende sa benefit na mapupunta sa community. Sino ba makikinabang dito? Unang-una syempre eto ba tumulong sa akin noong nakaraang eleksyon? Syempre magbabayad ka ng utang na loob. [It depends on the societal benefit. Who benefits from the projects? First of all, were these the people who supported me in the previous elections? Of course, you owe these people and you have to give something back,]” Jaafar says.

Legislators have long argued that development in the communities is supposedly the central aim of pork allocations.

Pork barrel funds “complement and link the national development goals to the countryside and grassroots as well as to depressed areas which are overlooked by central agencies which are preoccupied with mega-projects," write former House Speaker Prospero Nograles and Albay First District Representative Edcel Lagman in their 2010 paper "Understanding the 'Pork Barrel'."

The direct “affinity with the people” of the legislative branch of government, Lagman and Nograles say, makes the rationale for the pork barrel sytem.

Domingo notes that water supply projects need more planning before they could be implemented successfully.

“Kasi tubig is a basic necessity. Kailangan ng tao ng tubig, [Water is a basic necessity. Everyone needs water,]” he says. “Kailangan lang ayusin na the peso you put in gets, may return, societal benefit. [You just have to ensure that the peso you put in gets a return and benefits society.]”

Banluta, DILG’s water project officer, agrees. “Hindi lang sapat na basta lang nagpatayo ka ng facilities and then that’s it, [It’s not enough to build the facilities alone,]” she says, explaining that the soft aspect – capacity building – is as crucial as the water infrastructure.

“There has to be social preparation na mangyayari sa community level before you implement a water project. Para alam nila kung ano yung kanilang responsibilidad.. [The community has to be prepared before you could implement a successful water supply project. Residents should know their responsibilities…”], she says. — ELR, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular