The Filipino Rough Riders: The Philippines' Performers in 1899 America

I

n December 2024, Sofronio Vasquez III made the Christmas holidays happier for Filipinos when he became the first Filipino to win “The Voice USA.” Hailing from Misamis Occidental, he had been a “regular” in Philippine singing competitions before taking his shot in the US.

Vazquez's success story is not new to the world. Filipinos have been known to take center stage with globally renowned talents like Lea Salonga, Charice Pempengco, and Rachelle Ann Go.

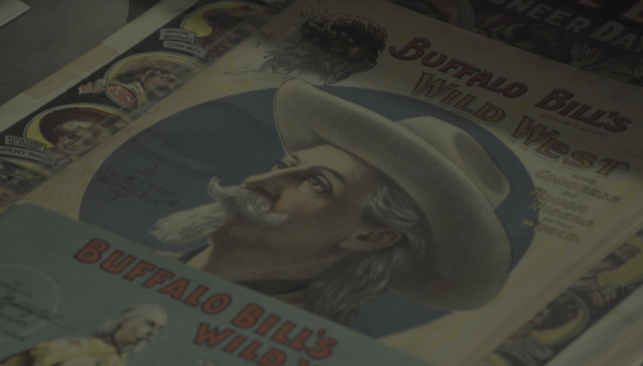

But unknown to many, Filipinos began to showcase their talents in the United States even before the 1900s. In 1899, three Filipinos were recruited to perform in US for "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show"—a spectacle that featured significant events in American history.

Filipinos appeared on the show for two seasons, but their impact on early representations of Filipinos in the US lasted longer than their stint in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Filipino showmen in the American West

I

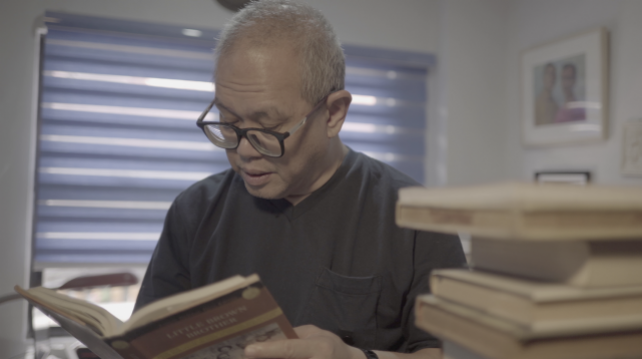

n 2022, Filipino-American researchers Emmanuel David and Yumi Janairo Roth from the University of Colorado Boulder met for lunch to catch up. Little did they know that their meeting would be the first of many as they found out they were both working on the history of Filipinos in the Mountain West.

During their research, they stumbled upon an unnamed Filipino in a scrapbook at the Denver Public Library. The photo sparked their curiosity about the history of Filipinos in the American West.Interested in the story that the photograph held, David and Roth took a trip to the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Golden, Colorado. The Buffalo Bill Museum, it turned out, housed the significant pieces for the puzzle that David and Roth wanted to complete.

“It's also one of the first places we saw another image that was in a weekly paper, and then where we also encountered the route books that had the names,” Roth recalled as she shared their first encounter with the Buffalo Bill Museum archives.

“What was really interesting was to come across... a small group of individuals named in a very particular and deliberate way,” she added.

The Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave also has a photograph of the Filipinos taken in April or May 1900. It showed the eight Filipinos who made up the Filipino troupe, collectively called the Filipino Rough Riders. They stood next to each other, with the only woman in the group—Ysidora Alcantara—in the middle.

They wore salakot, a Filipino hat, paired with what could be traditional Filipino clothes, modified for riding and paired with boots.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show

I

n the latter part of the 19th century, the westward expansion of the US began. During this period, the US presence spread across the Pacific, and Americans embraced the concept of “Manifest Destiny”—a belief that the US was meant to expand its forces across various states.

The westward expansion of the US was marked by stories of colonization and battles won by Americans to fulfill their vision of becoming the most powerful nation. Deriving inspiration from these narratives, William “Buffalo Bill” F. Cody established the Wild West Show in 1883 in Omaha, Nebraska.

“The Wild West show is a form of popular entertainment, but it was also this effort to blend fiction and reality. So there would be reenactments... that had conflicts between cowboys and Indians. The show itself starts bringing in a number of different troops, they were often referred to as Rough Riders,” David said

The name “Rough Riders” for the performers of the show came from the volunteer cavalry soldiers of America.

“The Rough Riders were actually a group of volunteer American soldiers. They were called the Rough Riders because of their rough living as soldiers in the field,” explained History Professor Dr. Jose Victor Torres of De La Salle University in Manila.

The Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show ran for nearly 40 years, traveling across almost the entire US and even Europe.

“The show covered 11,111 miles. Over 200 days, there were over 300 performances in over 130 cities,” David shared.

For every show, an estimated number of 15,000 people came to watch. Apart from entertainment, the show also became a platform for the US to showcase its “new possessions” from its colonies. These included Filipinos, who became part of the show after the Philippines was annexed from Spain through the Treaty of Paris in 1898.

When Spain lost to the US, several colonies came under American control—including the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Guam.

Before the turn of the century, the Philippines came under a new colonial power, and Filipinos were recruited to take part in the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in the US.

The Filipino Troupe

A

ccording to the paper written by David and Roth, the Filipino trio was recruited by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West manager, Ernest Cooke.

“So there were three performers in 1899, their names are Ysidora Alcantara, Felix Alcantara, and Geronimo [Inocencio],” Roth explained as she pointed to the Filipino names in the 1899 route book of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

In the 1899 program, the Filipinos were introduced as the season’s newest additions. They were viewed as the “strange people” from the new territories acquired by the U.S. at the end of the Spanish-American war. The Filipinos were seen as representations of what people in these new U.S. colonies looked like.

“In being Filipino, they would participate in these arena shows, and they would ride horses, and they would be present for the audience to see,” David added.

The participation of the Filipinos in the Wild West Show can be seen as a precursor to how Filipinos would later be exhibited in the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

While the Filipino Rough Riders were recruited to perform and may have had some agency in deciding to come to America, the circumstances were different for Filipinos who were sent there to serve as exhibits in what was called a “human zoo.”

“In order to show what they call the insular possessions, they needed to have a display. It was also a way of showing to the world that America was bringing "civilization" to these people. [...] For them, that was a classic show of “Here are uncivilized people,” that America brought democracy to them and made them civilized,” Torres said.

Another parallel between the experiences of the Filipinos at the 1904 World’s Fair and the Wild West Show was the unwelcoming treatment they received from Americans.

In the season’s opening performance at Madison Square Garden in 1899, Filipinos were met with a hostile reaction from the audience, as the show began only six weeks after the Philippine-American war broke out.

“As soon as the Filipinos enter the arena, they're basically greeted with hisses and boos. And, you know, you can think of like one person or two people hissing and booing, but when you think of an arena, [...] it was audible that they were the villains,” Roth recounted as she shared the experience of the Filipino troupe.

Despite this, the Filipinos went on with their roles for the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. From three, the Filipino troupe expanded further as five more performers were recruited in 1901.

Ysidora Alcantara

R

ising above the hostile treatment from the American audience, the only woman in the troupe, Ysidora Alcantara, continued to make a name for herself.

In the archives encountered by David and Roth, it was documented that Alcantara suffered a severe concussion after falling from a horse during one of the show’s relay race events. Embodying the true Filipina spirit, she returned the following year, like an athlete coming back stronger after overcoming an injury.

“And at least in the retelling of it, she’s kind of running her heart out and winning those relay races over and over again,” Roth said.

“In contrast to Buffalo Bill Cody, the white male figure at the center stage, [...] we have a Filipino woman who is seeing the world, who is traveling and riding at full speed on this horse. And it's quite an incredible story,” David added.

Alcantara’s uniqueness didn’t end with her unmatched performance in the relay race events of the Wild West Show. Her remarkable performance made her a subject of interviews—which eventually helped David and Roth to discover her last known address in the Philippines.

“What I love is back in the old days in newspapers is they used to just [...] write somebody's address down. And so we read this, they introduce Ysidora and they say 34 Street Royal,” Roth fondly recalled when asked how they ended up in Cavite.

David and Roth came to Cavite to look for Calle Real. They were later introduced to a local historian who showed them a Cavite history book that listed the surname Alcantara in the towns of San Rafael and San Roque.

However, they were unable to trace any possible relatives of Alcantara in Cavite.

Wilfredo Pangilinan, a member of the Board of Directors of Cavite Historical Society suggested that the Alcantara clan may not have been well-known in the province. He also theorized that Alcantara may not have returned after leaving for the US in 1899.

“There was no explanation about the Alcantara family. It could be because they weren’t well-known people. If they were, there would have been some mention of them here, including an explanation about their lives, and their decision to leave for America,” Pangilinan said.

All their efforts were not in vain, as David and Roth saw the opportunity to locate Alcantara’s possible hometown as a chance to shed light on her life before becoming a performer in the US.

“Coming to a place like Cavite is about bringing a particular specificity to the participants' lives, [...] not just an abstract location that they were just from the Philippines, we can trace them back to a particular location where we can imagine them living and that helps us better understand their origins prior to going to the States,” David said, explaining the significance of searching for Alcantara’s roots in Cavite.

A Filipino Footnote in America

A

sked why it was important for Filipinos to know about the story of the Filipino Rough Riders, Roth had to say, “It's a forgotten piece of history. It's important because it's telling a story that hasn't been told.”

More interestingly, the Filipino troupe seems to be guiding the search of David and Roth about their lives. As they continued their research, they stumbled upon a second photograph taken in October 1900, which appears to tell a different story from the first photograph they found, taken in March of the same year.

“There's an affection between them. They have their hands on each other's legs or their knees. And they feel close to one another, like a close group of friends, like a barkada, like a close friendship circle,” David said, describing the differences in the second photograph, which features seven out of eight Filipino troupe members.

“But we think all eight are present. And part of that has to do with a belief, just because of how they're engaging with whoever is photographing them, that the eighth person is actually one of the Rough Riders, but has a camera and is documenting, as one might document a family,” Roth said.

Apart from the apparent friendship built among the Filipino troupe, their being alive at a time when the Philippine-American war was ongoing can also be seen as a form of resistance.

“In contrast to the negative representations in the paper, this group of performers, they were displaying themselves as alive, as organized, as a collective,” David said, explaining the message behind the October 1900 photograph, where the Filipino troupe is seen carrying the Philippine flag.

In years of trying to uncover the story of the Filipino Rough Riders, David and Roth have encountered several questions.

One of these is how they located the photograph, to which they usually respond, according to David, “Actually, the Filipino Rough Riders found us. They wanted to be found. [...] This is an incredible story of this group of performers themselves [who] wanted to emerge from the dusty archives and make themselves present again.”

But there is more to discover about the story of the Filipino Rough Riders. To ensure that awareness of their story grows, David and Roth have been conducting activities under the “We are Coming Project”—a collective effort to recenter the sidelined story of Filipinos in the Wild West Show.

Among the activities is the installation of marquees at various sites in the U.S., where the names of the eight Filipino Rough Riders were illuminated in vintage theatres. The project also includes printing a yellow broadsheet with summarized information and photos of the Filipino troupe.

The traveling show, which featured Filipino performers, was also brought to life through their collaboration with Filipino sign painters who worked on placards with texts that replicated what could have been the promotional materials of the Wild West Show during that time.

Photographs have always been powerful in encapsulating a moment in time, which is proven in the way that the sense of camaraderie of the Filipino Rough Riders was preserved in their October 1900 photograph. On the back of the photograph, an inscription reads, “Remember to Buffalo Bills Wild West the Filipinos Troupe.”

The inscription seems to be a message to future audiences to remember the lives of the Filipino troupe—a group of talented entertainers who may have been the first Filipino performers in America.“This story is important even though it is a small piece of history because we can see here how other nations perceive us as Filipinos—not how we perceive them, but how they perceive us,” Dr. Torres said when asked about the role that the troupe played in the early representations of Filipinos in America.

There is still so much to uncover, but with the work done by David and Roth, there is already so much for Filipinos to be aware of and remember about the story of the Filipino Rough Riders.

With their call to be remembered, it is a constant reminder for Filipinos in different parts of the world to think of the Filipino Rough Riders every time a talented individual from the Philippines creates shockwaves in the global entertainment scene.

As David believes, the continuation of the “We are Coming Project” is living proof that this footnote of Filipino history in America is not forgotten, “In some ways this is fulfilling their wish to be remembered. Both as a group, but also individually. And they're not lost to history.” –NB, GMA Integrated News

Photos by Kim Shively (Colorado, U.S.A.), Joshua del Rosario (Cavite, Philippines), Marco Felipe Lopez (Cavite, Philippines)