Why a lower debt ratio is good for the PHL

The Philippines now carries one of the lowest average debt ratios in Asia, a product of three decades of economic reforms.

“The country emerged from being a highly indebted developing country in the 1980s to become one of the fastest-growing emerging economies with debt ratios lower than its Asian neighbors,” the Department of Finance said Wednesday.

This may not carry a significant message to most of the 100.95 million Filipinos, but it actually affects their daily life, economists told GMA News Online.

A debt ratio is the ratio of total debt to total assets, and is expressed in percentage. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas defines the country's external debt ratio as its "total outstanding debt expressed as a percentage of annual aggregate output."

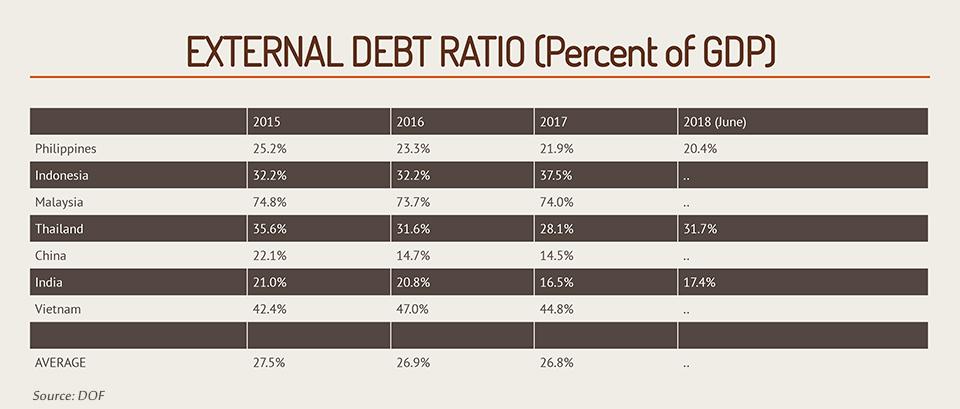

“As percent of gross domestic product (GDP), the Philippines has an external debt ratio of 20.4 percent as of June 2018, lower than those of Malaysia (74 percent), Vietnam (44.8 percent), Indonesia (37.5 percent) and Thailand (31.7 percent), but slightly higher than those of India (17.4 percent) and China (14.5 percent),” the DOF said.

“The average for seven major Asian countries is 26.8 percent, which is more than 30 percent higher than the Philippines’,” it added.

In response to an email query, Finance Deputy Secretary Gil Beltran enumerated the consequences of a lower debt ratio to a country and its people.

“This means that we, Filipinos, have:

“a. More foreign exchange resources available for investment and consumption and have more economic opportunities to advance our well-being; and

“b. Have an economy that is less vulnerable to external economic crises and disturbances and that we can grow incomes faster and create more jobs domestically than before,” Beltran said.

Stoking growth

The significance of a lower debt ratio to the larger economy is that a country tends to be able to have a higher level of funds to stoke economic growth, economists said.

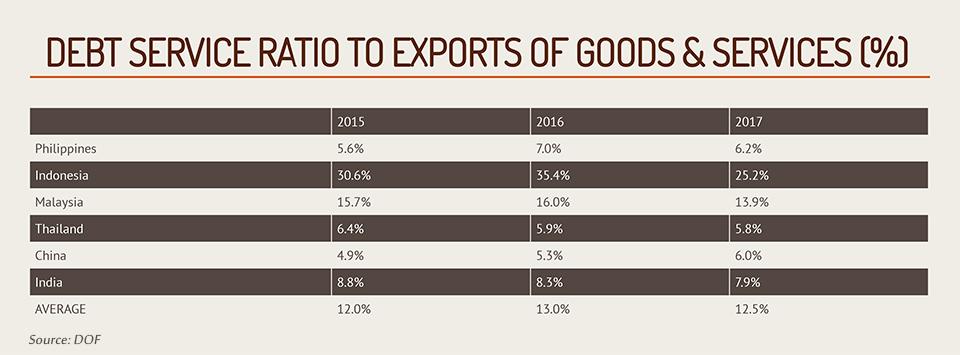

“From 324.8 percent of exports of goods and services in 1985, the Philippines’ external debt declined to 47.9 percent in June 2018. From 64.6 percent of exports of goods and services in 1985, the country’s external debt service declined to 6.2 percent during the first half of 2018,” the DOF said in its Economic Bulletin on “External Debt Ratios.”

“It is significant news because lower debt service as percent of exports implies that the country has more resources for raising domestic productivity and capital formation,” Cid Terosa, dean at the University of Asia and the Pacific School of Economics, said in a text message.

He noted that the money the country uses in paying off its debt does not yield any return.

“Debt service is an outflow of resources that cannot be recovered. Hence a lower debt service implies more choices and opportunities for domestic economic growth and development,” Terosa noted.

“If used effectively, resources meant for debt service can now be used to help improve material well-being of Filipinos,” he said.

Lower debt service “means that we have more resources for more productive activities that can contribute to economic growth. What is used for paying off debt can now be used for infrastructure and human capital development,” Ruben Asuncion, chief economist at Union Bank of the Philippines, told GMA News Online in another text message.

Thirty years of reforms

The reversal of the country’s debt position did not come overnight, the DOF said. It was a product of three decades of economic reforms, including:

- Fiscal consolidation. The country reduced the fiscal deficit by increasing the tax effort from 10.1 percent in 1990 to 14.2 percent in 2017 and reining in on expenditures so that the targeted deficits averaging 2.1 percent of GDP for almost three decades are attained.

- Prudent economic management. Major infrastructure projects were subjected to economic evaluation so that only projects that matched or exceeded the EIRR (economic internal rate of return) benchmark rate of 15 percent was implemented and those priority projects that failed to reach the benchmark used ODAs (official development assistance) with softer terms.

- Debt management. The country reduced debt service thru debt rescheduling initially, and later, debt conversion and debt exchanges, shifted to domestic borrowing to reduce forex risk exposure as domestic savings rose and domestic capital markets grew, and focused on longer debt maturities.

- Shift toward market-determined exchange rate. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas shifted to a market-determined exchange rate to ensure competitiveness and relieve pressure on the balance-of-payments.

- Export and investment-friendly regime. The incentive structure was enhanced to remove bias against exports thru reduced tariff rates and tariffication of quantitative restrictions.

How does all this translate to the economic welfare and financial well-being of the Filipino?

“It may mean more jobs and other economic opportunities for Filipinos. This can translate to stronger buying power and can further add to more economic growth,” Asuncion said. —BM, GMA News