Filtered By: Topstories

News

DMCI: Rizal Monument originally meant to be 'wrapped' in 'massive wall' of buildings

By MARK MERUEÑAS, GMA News

The Rizal Monument was originally planned to be surrounded by a "massive wall" of government buildings, and was not meant to have a view of the sky in the background, the builder of the Torre de Manila said in a memorandum to the Supreme Court.

DMCI Homes said in its 112-page memorandum to the SC that they did not violate any law or obstruct the visual corridor or sightline of the monument when it constructed the 49-storey Torre de Manila almost a kilometer away from it.

DMCI asked how can it mar the monument's sightline when Daniel H. Burnham, the original architect of the Luneta Park (known as the Wallace Field during the American occupation), did not even intend to have a clear sky as a backdrop to the Rizal monument.

Burnham was a well known Chicago building architect who was commissioned by William Taft, head of the second Philippine Commission to be Manila's master planner.

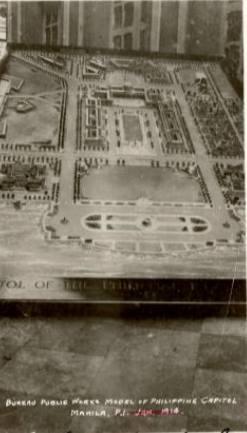

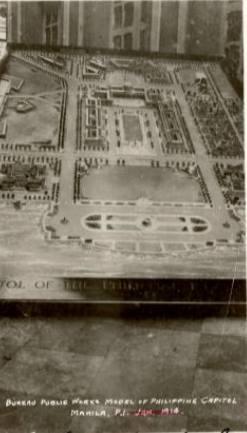

Quoting architect Paulo Alcazaren's book "Parks for a Nation," DMCI said that in his original plan, Burnham had intended to have a civic mall or a civic complex surrounded by buildings, including a cluster of government buildings at its eastern portion to be collectively called the "National Group."

This cluster included the Capitol Building, which was to house the legislature, the various department buildings, museums and libraries. At its center was the Rizal Monument serving as Manila's equivalent of the Washington Monument.

"From its location, the monument of Dr. Rizal would have no skyscape or a view of an expanse of the sky; the viewer would see the monument wrapped in the shadow of the buildings around it, with the Capitol looming as a backdrop," said the DMCI.

"As originally designed, the Rizal Monument was part of the Burnham Plan for a Mall at the Luneta, a section of the city sealed off from vehicular traffic and enclosed by a Philippine Capitol and other public and semi-public buildings. The monument was to be viewed with a backdrop of government buildings, not the blue sky," it added.

Burnham's plans for the "civic core" at the old Luneta grounds was never implemented after the Republicans lost the 1912 US elections and the new administration controlled by Democrats implemented a policy that eventually led to the letting go of their far-flung island colony.

The DMCI noted that though Burnham's plan never pushed through, a 1930s zoning map of Manila still showed the Luneta as the site of a government center, with the proposed Capitol and the Spanish-era hippodrome drawn in the map.

The DMCI said that even in the 1960s, people visiting the monument were "unmindful" of structures "dotting the horizon and forming its skyline," including two giant smoekstacks of the Meralco powerplant and government buildings like the Philippine Senate, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Finance, and the National Library. The buildings were later obscured by foliage from growing trees planted around the monument.

DMCI said it was only decades later, in the late 1980s, when the sky became part of the monument’s backdrop.

This happened after the National Parks Development Committee (NPDC) decided to cordon off the monument and installed a row of nine stainless steel bollards 32 meters away from the monument's base. The grass field on both sides of the monument were also roped off.

The NPDC did this upon the request of honor guards, who complained that rowdy crowds watching the "changing of the guards" would poke fun and throw things at them.

"The unintended consequence of this action was to deprive the visitor of an ideal view of the monument, which was nine meters from the base of the monument. The extended viewing distance caused by the barriers minimized the silhouette of the Rizal Monument, which receded into the horizon against the backdrop of the open sky," said the DMCI.

To get the ideal viewing distance for the Rizal monument, the DMCI turned to mathematical sciences professor and author John D. Barrow from the University of Cambridge.

Barrow calculated the ideal viewing distance for monuments to be "the geometric mean of the height of the pedestal and the height of the statue, or , with Y as the viewer, T as the height of the pedestal, S as the height of the statue, and x as the ideal viewing distance."

Using Barrow's calculation, the DMCI calculated the ideal viewing distance for the Rizal Monument is 9.1225 meters away from it, given that the height of its obelisk is 8.9 meters, the granite pedestal is 5.1 meters and the marble steps is 0.6 meter, for a total height of 14.6 meters.

However, after the government cordoned off the viewing area around the monument and put barriers 32 meters in front of the statues, the public can no longer marvel at the monument from the ideal viewing distance of 9.1225 meters since the 1980s.

"The NPDC deprived visitors of vista points that offer the best possible view of the monument from all sides. What they got instead was a landscape view of the monument, consisting of 70% blue sky and pavement, 20% foliage, and 10% monument," said the DMCI.

"Through time, repeated exposure to this postcard view conditioned people’s minds to its acceptance. Since the blue sky was neutral and was not offensive, they became accustomed to viewing the Rizal Monument as a relic to be revered from a distance," it added.

The move by the NPDC "subconsciously created" the idea that the sky was part of the view when visiting the Rizal monument.

"The image of the Rizal Monument as shown in countless photographs since then was the result of nothing more than thirty years of being conditioned to look at the monument, framed by foliage, from a distance," said the DMCI.

If the bollards were removed or set back to allow an ideal viewing distance, the sky would become irrelevant, the company added.

The DMCI branded as a "hoax" claims by the Office of the Solicitor General's claims in its Position Paper that “the obelisk, the statue and its sightline constitute an integrated whole” and formed part of the “physics of the Rizal Monument.”

The monument, based on a model called "Motto Stella," as designed and executed by Swiss sculptor Richard Kissling did not include a view of the sky. No existing law or ordinance mandates a sightline.

The DMCI added that when the National Museum declared the monument as a national cultural treasure on November 14, 2013, it did not include the skyscape, the line of sight, vista point, or view corridor of the monument.

"The national cultural treasure was the physical monument itself, not its setting," said the DMCI.

In its memorandum, the DMCI pleaded anew that the temporary restraining order against the construction of the condominium be lifted. The firm said the suspension of the construction and development of Torre de Manila unjustly deprives DMCI of its right to build on its property without due process of law.

DMCI also insisted that the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, the National Museum and the National Commission for Culture and the Arts have no jurisdiction over Torre de Manila.

Likewise, the DMCI said the City of Manila may not be compelled by mandamus to revoke the permits and licenses issued to the property developer, as well as to order the demolition of Torre de Manila.

"To allow the Torre de Manila to rise against the backdrop of Jose Rizal’s monument is not to tarnish his memory or overshadow his greatness as a national hero. Rather, to allow the Torre de Manila to stand tall behind Jose Rizal is a towering manifestation that this Honorable Court is firm in its commitment to uphold the rule of law," the memorandum stated. — ELR, GMA News

Tags: torredemanila

More Videos

Most Popular