Late response, clunky policies leave Saudi OFWs, kin in misery

A few weeks before Father's Day in 2015, Noli Cagayan called home to say that he's going back to the Philippines, permanently.

"Uuwi na ako ng 30, bibili na ‘ko ng ticket kinabukasan," he told his wife.

Noli had spent nearly three decades working in Saudi Arabia, but things had taken a downturn after the sudden drop in world oil prices rocked the kingdom. Two months had passed since Saudi Oger Ltd. had paid his salary.

The 50-year-old was primed for retirement even without the urgency imposed by Oger's financial collapse. With the youngest of his four children nearly finished with school, he figured he no longer had much reason to work abroad.

To prepare for his trip home, he sold his van, which he had used to ferry himself and other workers — some of whom he personally recruited during his vacations in the Philippines — to two different job sites.

Days before his flight home, Noli suffered a heart attack.

“Papasok na siya. Bigla na lang siyang, ‘yun, inatake. ‘Di na natuloy. Kaya namatay siya nung Father’s Day," his widow Charito told GMA News Online at their home in Valenzuela.

The house, a small one-story rental, has gone unpaid for five months. Their children Dincy Joseph, Daisy Jane, and Charles Cagayan are doing their best to fix their home and pay the bills.

But a significant chunk of their family income has gone into paying for the education of their youngest sibling Charmaine and for claiming benefits from the Overseas Worker's Welfare Association (OWWA).

Charito estimates that the family has spent some P70,000 in the past year trying to claim her husband’s unpaid salary of two months from Saudi Oger and benefits worth P400,000 from the OWWA.

“Bagsak ang Saudi Oger ngayon,” Charito said.

“Lahat ng mga nagtatrabaho dun stranded, wala na silang makain, namumulot na lang ng kakainin. Ilang buwan na silang naka-stuck, lahat ng mga kasamahan niya wala nang trabaho, nandun na lang sa bahay, nasa kampo na lang sila," she added.

Before Noli's sudden death, Charito had applied to claim his OWWA benefits. The money they would have gotten from the government's various programs for OFWs would have paid off their debts, transferred a land title from Noli’s parents to their name, and funded their own business.

They got back his remains from Saudi Arabia 45 days after his death, but since then, the family has had little to show for their efforts. Last April, the got P15,000 from the Livelihood Component of OWWA’s Education and Livelihood Assistance Program (ELAP) for deceased OFWs.

“Nasa 28 years siya sa Saudi, sa iba-ibang company. Inabot siya nun ah, kulang 30 years,” Charito said.

“Alam naman nila na every time na uuwi siya yearly, meron siyang, may binabayad siya dun. Kaya kumbaga, bakit naman yun lang ang nakuha ko?” she added.

OWWA Deputy Administrator Josefino Torres said the problems plaguing the Cagayan family was not necessarily due to the government’s neglect, but a misunderstanding among OFW families on how claiming benefits work.

“Hindi porke namatay ay pwede nang ano kasi our system here, as far as the death benefit is concerned, is like an insurance coverage. Ang insurance coverage, you only get when you are active,” Torres said.

“If the death occurs two months after effectivity of membership, pwede pang mag-claim ang heirs mo ng death benefit. Ang problema, most of these people in camps, nag-expire na ang membership nila with OWWA, so their heirs are no longer entitled to claim their death benefit," he added.

Torres said OWWA could not simply give out benefits to OFWs, because in the end, they could also end up in hot water.

“'Di naman kami pwedeng bigay ng bigay kasi ano kami talaga, accountable kami dito," Torres said.

"We need also to buttress ourselves from blame. ‘Pag hindi naming ginawa ito, according to our set of accounting rules and regulations, patay kami ,” he added.

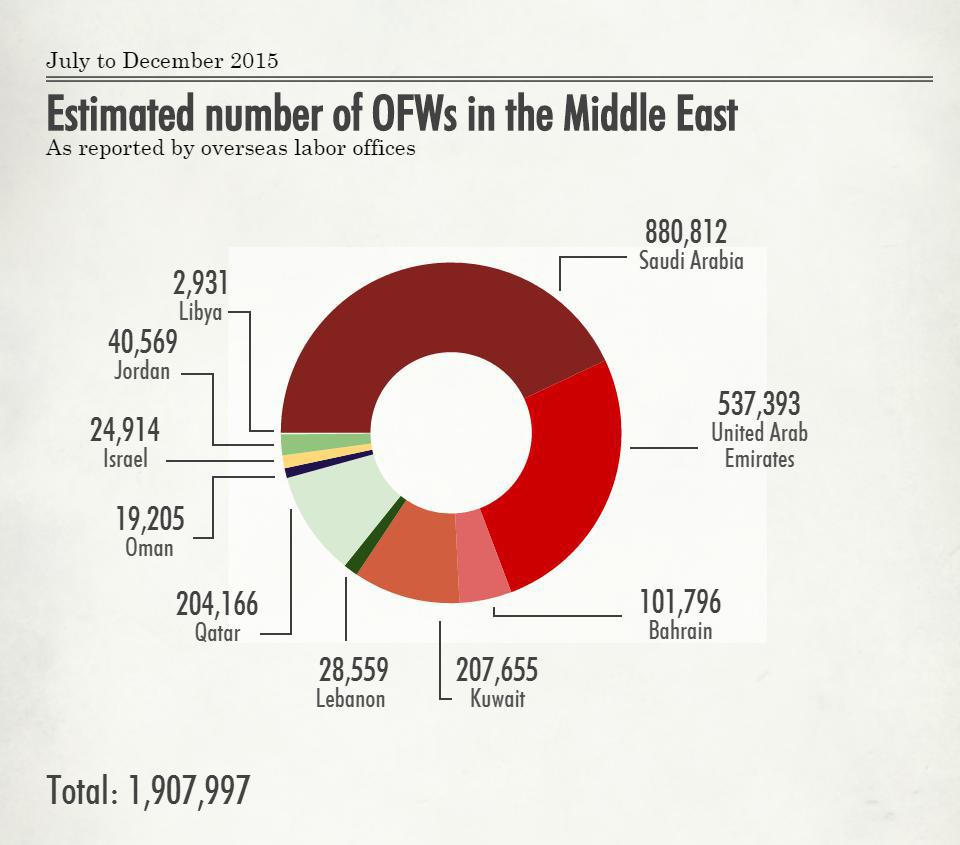

Noli Cagayan was just one of the more than 800,000 estimated OFWs in the kingdom as of last year.

In a report submitted to the Senate this month, OWWA described Saudi Arabia as “admittedly one of the oldest markets for OFWs” as Filipinos began “trooping en masse” to the country in the early '70s.

In his book “Saudi Arabia,” Dr. Sherifa Zuhur wrote that Filipinos began migrating to Saudi Arabia for work in 1973 in various fields such as the health, oil and manufacturing, and service sectors.

But the economy of the oil-rich kingdom took a massive hit after world crude oil prices began to drop in 2014 due to a glut in supply. From $100 per barrel in 2014, prices dropped to as low as $26 in February, before rebounding to $50 in June this year.

Because 73 percent of the government's budget is dependent on oil revenue, Saudi Arabia's estimated budget deficit rose from 3.4 percent of its Gross Domestic Product in 2014 to 16.3 percent in 2015.

This, in turn, led to massive retrenchment among workers. As early as 2014, the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) had been in contact with companies such as the Mohammad Al-Moji Group (MMG), one of the first companies to reduce the number of its Filipino workers.

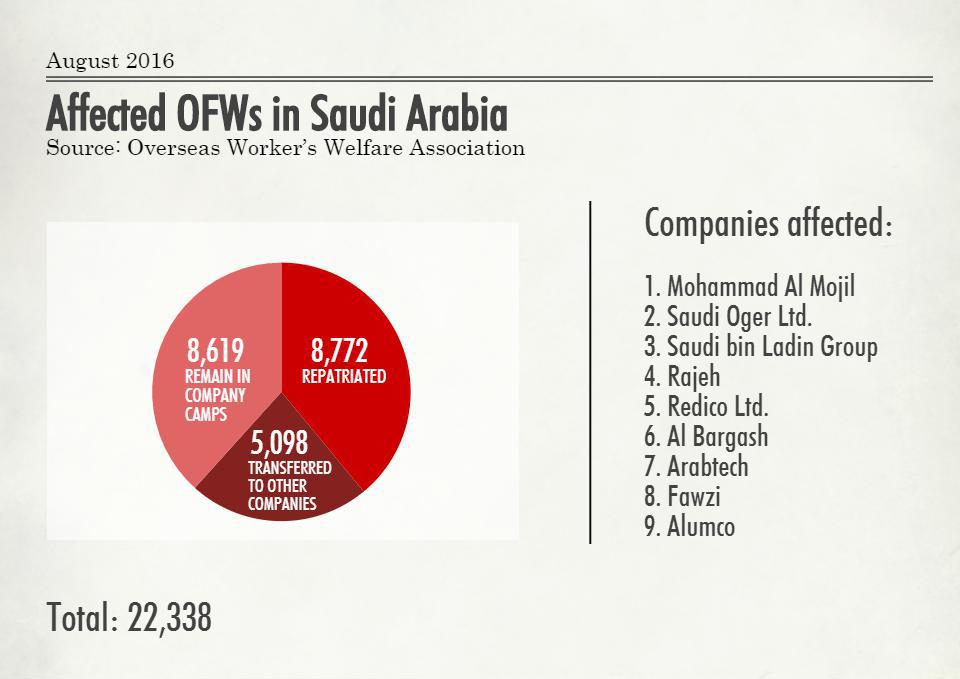

OWWA has identified some 22,338 Filipino workers from nine major companies affected by the oil crisis. Of these, 8,772 have been repatriated while 5,098 have been transferred to other companies and 8,619 have decided to remain in company camps.

For some, the situation has been truly dire. Workers have been reduced to sleeping on cardboard boxes and rummaging trash cans for food. The Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) has received reports that some retrenched OFWs have tried to commit suicide out of frustration.

Among those who have chosen to stay in the camps is Edelberto Araja, who took a job in Saudi Arabia 10 years ago to provide for his family after his cocolumber business fell apart.

“Nagpunta siya ng abroad kahit ayaw niya para mapagpatuloy lang ng mga kapatid ko yung pag-aaral,” Mark Arvin, Edelberto's eldest child, told GMA News Online.

“Kahit wala siyang experience sa pag-aasikaso ng kahit anong papel. Lakas lang ng loob," he added.

Sharing his father's dream for his siblings, Mark dropped out of school years after his father left. Instead of wasting resources, he said, he would rather help his father make sure that his younger siblings make it.

But for the past six months, he carried a secret of his father’s that would derail their plans: Edelberto, like Noli Cagayan, had not seen a paycheck in months.

Leftover savings allowed Edelberto to keep up the ruse, until news of widespread joblessness in Saudi Arabia reached the Philippines.

Edelberto considered the government's offer of repatriation and application into its Relief Assistance Program (RAP) for stranded OFWs worth P20,000.

In the end, he decided to stay in a camp to pursue a case against his employer for his end of service benefits, and so that his family could claim an additional P6,000 from OWWA.

Workers are no longer entitled to receive the additional P6,000 meant for their families if they apply for assistance after their repatriation.

“Pwede naman dapat talaga siya umuwi kasi pagtutulung-tulungan namin yun,” Mark said.

“(Pero) inaantay talaga niya yun kasi yun yung ipagsisimula niya dito pag umuwi siya. Yun yung parang gagawin niyang puhunan para hindi na lang ulit siya babalik sa abroad,” he added.

But if the crisis started in 2014, why does it appear that the government is addressing the situation only now?

Susan Ople of the Blas F. Ople Policy Center & Training Institute said that OFWs had sounded the alarm about the impending crisis in Saudi Arabia long before the government organized its response.

“I remember also verbally discussing this with some officials of DFA and DOLE. Kasi nga we were also being appraised of the situation by Filipino community leaders in Saudi Arabia. I remember that siguro mga August or the last quarter of 2015, the Ople Center was already calling for a team to go to Saudi Arabia,” Ople said.

“When the prices of oil were dropping we were already alerting the government na imposibleng walang impact ito. But I guess it’s easier to react 'pag andyan na,” she added.

OWWA Deputy Administrator Josefino Torres defended the agency, saying that it had sent help early on.

“Yung financial assistance ngayon lang. Pero ang assistance it came in the form of food, etcetera, dun sa camps. Noon din, right there and then, nung 2014,” Torres said.

“Before meron, kumbaga, sporadic assistance, hindi organized. Ibig sabihin, ‘pag pupunta yung team, okay, may dala silang food. Provisions, supplies. Pero ngayon, mas organized kasi," he added.

But Torres himself admitted that the agency was surprised by the scale of the problem.

“Yung magnitude, aware kami, mababa lang yung magnitude. Kumbaga, ang sabi ko nga kanina, one or two companies pa lang yung... We did not realize that, kumbaga, widespread na ‘yun,” he said.

Last March, the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) sent a team to Saudi Arabia to assess the labor situation in Saudi Oger Ltd., Mohammad Al Mojil Group (MMG), and Saudi Bin Laden Group.

It was followed by another mission in May that came up with an initial list of nine companies that retrenched workers due to the oil price drop.

The list quickly became outdated as workers from affected companies that were not included showed up at diplomatic posts for financial assistance.

A second OWWA board resolution was passed on August 11, 2016 approving the expansion of the list of beneficiaries for OWWA’s RAP.

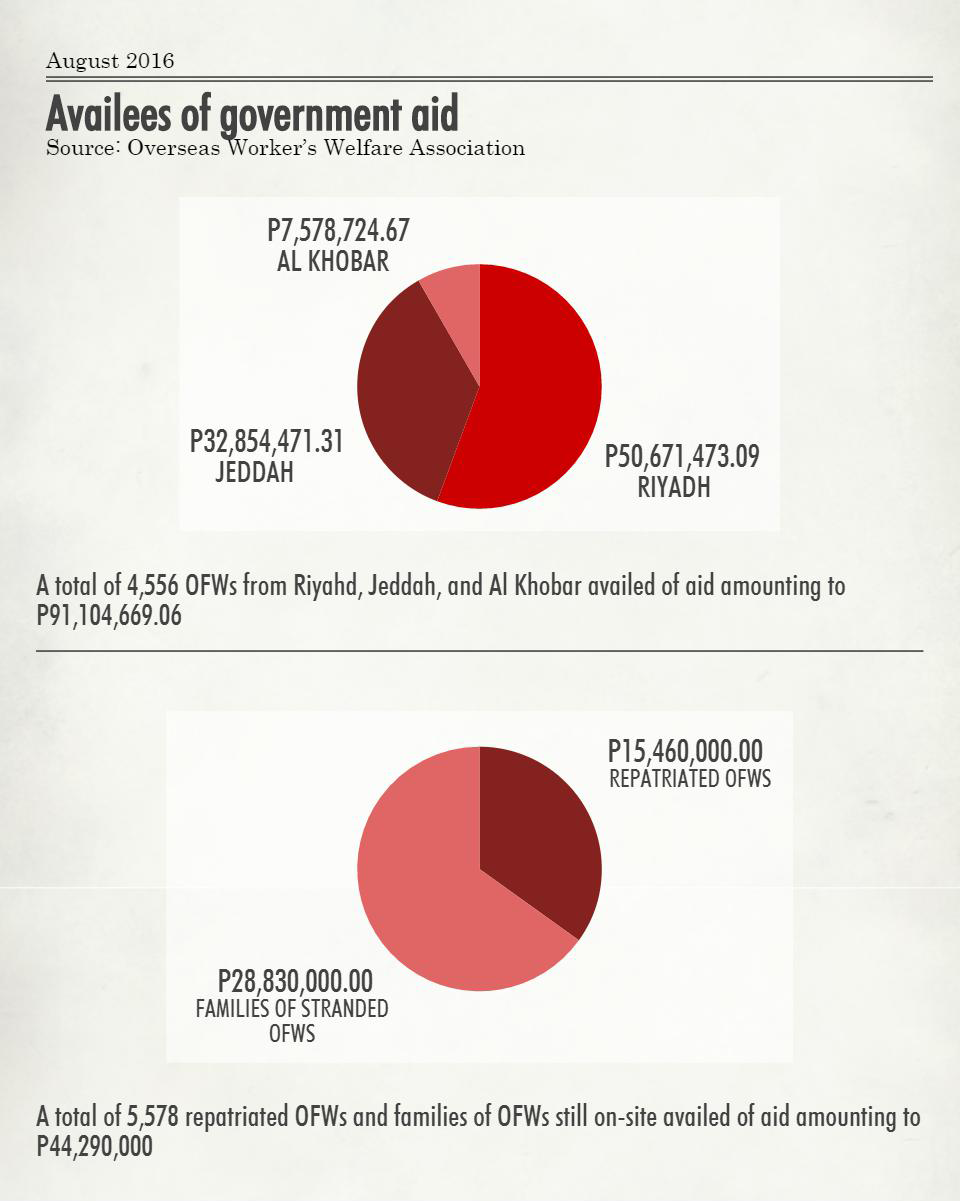

As of August 15, a total of 4,095 OFWs in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Al Khobar were granted SR 1,590 or P20,000 from the P500-million aid approved by the OWWA board for workers from the nine companies.

Torres defended the seemingly slow process of providing aid.

“We had to ascertain the conditions. Hindi naman pwedeng basta-basta mag-act dun sa Saudi Arabia. It’s another country, another set of rules to work with. We had to work also with our Embassy doon sa Saudi Arabia, who is working with the authorities there,” Torres said.

“For instance, there is seemingly alarm in Riyadh that we’re transferring so much money. Dito wala, kasi kita naman dito yung ating purpose eh, so na-transfer natin yung pera. Pero pagdating mo ng Saudi Arabia, we need to negotiate the smooth transfer of money to the hands of our people from the banks. Kasi may mga precautions to prevent money laundering, etc.” he added.

Securing the money while being transferred to work camps, and the safety of personnel bringing this money, Torres said, was the only real delay in transferring aid to OFWs.

On Wednesday, Labor Secretary Silvestre Bello III promised 129 newly-arrived OFWs at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport that lawyers sent by the government to Saudi Arabia to assist Filipinos would not go home until all their benefits had been claimed.

President Rodrigo Duterte also promised to fast-track benefits for OFWs and to link repatriated workers to other government initiatives until they are able to work again.

The ability of the government to create a response in a short time, after nearly a year of being ignored, has come as a surprise to OFWs and their families, according to Ople.

“The workers were telling me, ‘Ma’am, pwede naman pala na mabilis mag-aksyon yung OWWA na magbigay ng financial assistance sa amin. Pwede pala na iba’t-ibang ahensya makarating sa amin,’” Ople said.

She explained that the response was hastened because of: a better understanding and appreciation of “the gravity of the crisis and its social dimensions”; better “decision-making at the very top” ; and “external pressures” like foreign governments such as India and France negotiating “the best term for their workers” ahead of the Philippines.

But Ople said that OWWA still had a lot of work to do in terms of reaching out and making itself accessible to workers.

“OWWA continues to stay in their comfort zone of dealing lang with traditional media and waiting for walk-in clients. They haven’t really embraced social media, which is sad for me because most of their clients abroad are accessible through social media,” Ople said.

“Hindi ba pwedeng, with the size of OWWA and the resources at its disposal, ‘di ba sila pwedeng mag-create ng social media team na makulit sa pagpapaalala and can clarify these questions not only for beneficiaries abroad but the families here? Communications has always been the weak link of OWWA and I think even our embassies and consulates," she added.

But even with their misgivings, OFWs and their beneficiaries feel they have a higher chance of getting their benefits and back pay with the help of the government.

“I think with this administration, the chances are higher dahil I don’t think the president will tolerate an Embassy accepting money meant for OFWs and not turning this over. The question really is how long it will take?” Ople said.

The DFA said that while the oil crisis, which it calls an “experience that is common to all oil-producing countries,” has no effect on the diplomatic relations between the Philippines and Saudi Arabia, it certainly would have an effect on the next generation of Filipinos who plan to work abroad.

In its acknowledgement of the shortcomings of the Philippines’ Saudi policy, OWWA said the current situation of OFWs called “for a fresh and more serious policy rethinking and reset on the whole arrangements that’s responsible for sending domestic workers to Saudi Arabia.”

“Perhaps, the debate should go far beyond merely enunciating constitutional right of Filipinos to travel. It should be carefully balanced with the capability of the State to deliver on its mandate 'to provide protection to all citizens whether here or abroad..."

“The Department should, henceforth, adopt a resolute, coherent , consistent and sustainably long-term policy position on it; (a) deployment policy to Saudi Arabia, with emphasis on vulnerable workers group.”

These policy changes, at the moment, remain vague as the government continued to focus on giving emergency aid.

“It wasn’t really on the radar screen of the policy decision makers,” Ople said.

“Maski nagpalit na yung secretary, the people in charge are still there. They’re still part of the bureaucracy," she added.

Ople said one possible step the DOLE could take was to improve the government’s ability to prepare for and prevent large-scale crises such as this.

“At a macro level, we need to deepen our economic intelligence. There were signs already that these companies were already in trouble. Sabi nga ng OWWA, 2014 meron na,” Ople said.

She ticked off the lessons that should have been learned from the experience in Saudi Arabia.

“Number one: not to be complacent. Hindi porket marami pa ring job orders, ibig sabihin the economy of the country is general… Pangalawa, I think, nakita rin natin na we need to also diversify our markets," Ople said.

"Not that we want to push our workers to leave, but if you see that the Saudi and other Middle East countries are struggling, then why would you want to see more of your workers going there? Feeling ko lang, in anticipation of a similar crisis in the future, baka we need to look at the mandatory insurance,” she added.

If and when the government institutes these changes, it will be too late for Noli Cagayan, Edelberto Araja, and their families.

Yet it might ultimately prove to be a blessing for two of Cagayan’s children, who headed to Singapore and Malaysia after their graduation for the same reasons their father left for Saudi Arabia 24 years ago. They are now second-generation OFWs.

But Charito Cagayan isn’t concerned with the future or with policies in which they don’t have any direct say. For many OFWs, what matters is getting help, now.

“Wala na silang makain, ilang buwan na silang naka-stock- lahat ng kasamahan niya, wala nang trabaho, nandun na lang sa bahay, nasa kampo na lang sila. Yung iba, umutang na lang para umuwi, para makauwi lang sila. Hanggang ngayon, wala pa silang sahod,” Charito said.

It would help too, if families finally get the benefits they feel they deserve.

“Yun lang talaga ang inaasahan namin sa ngayon. Nakapagpatapos yung mga anak ko, umutang ako ng 5-6 para lang makatapos sila dahil nga sa nangyaring yun. Wala na talaga. Kaya ngayon, ang iniisip ko, sana naman po, maibigay na yung benefits” Charito said.

"Tulungan niyo po," she added. —with additional graphics from Jannielyn Ann Bigtas/JST/NB, GMA News