ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Genuflection according to Iggy Rodriguez

By Katrina Stuart Santiago

In a daily landscape riddled with notions of religion and religiosity, where impeachment trials begin with a prayer for national unity, even as the more powerful easily and always spout Catholic rhetoric to justify faults and abuses, here where the poor are taught to be thankful and hopeful because God will provide, there is necessary unease in the idea of genuflection. In fact, in Iggy Rodriguez’s hands, we are told that this act of bowing down to the sacred is equally about those who imagine themselves the most sacred of cows, and those who we have allowed to become worthy of genuflection. Both can only echo our discomfiture at being told we are so much smaller than we think.  “Genuflect” is a small exhibit, in a small gallery, that echoes far louder than most work that gets in your face about and against our contemporary notions of faith and Catholicism. The pièce de résistance takes up a third of the floor space, with an installation of a miniature cathedral, doorways filled with three Christ child icons, all in various states of deterioration. Now those seem like objects asking to be found by the luckier of artists, but it is also telling of the excesses of an institution that likes to deny its wealth. Of course, falling into the hands of Rodriguez, what these found religious icons become are object and subject for discourse on the enterprise of religion and faith, sacredness and everything it represents, tied together by structure and image that are familiar. What works here more than anything is the attention to detail, which must begin with the decision at details that are pertinent to the discussion at hand. The dirtied and dismembered Christ child icons are encased in a miniature cathedral that’s layered with symbols of violence (toy guns and soldiers) and sin (serpents). The whole structure stands, the floor is filled, with plastic toy centipedes, which in this number and context resonate as symbolic of instability and ruin, if not just the venomous and evil that’s here. Entitled “Annuit Coeptis,” which literally translates to "He approves of the undertakings," with a rendering of the Eye of Providence or what’s considered as the “All-seeing eye of God,” here is work that points a finger at the ways in which this Catholic faith allows for evil, and is actually an enterprise that’s complicit in these forms of violence. Though probably what astounds more, what could be the bigger work here, are Rodriguez’s untitled series of pen and ink works, all only lettered for classification purposes, and all revealing the same attention to detail that’s in the bigger installation, and all working from it, maybe off it, if not against it, too.

“Genuflect” is a small exhibit, in a small gallery, that echoes far louder than most work that gets in your face about and against our contemporary notions of faith and Catholicism. The pièce de résistance takes up a third of the floor space, with an installation of a miniature cathedral, doorways filled with three Christ child icons, all in various states of deterioration. Now those seem like objects asking to be found by the luckier of artists, but it is also telling of the excesses of an institution that likes to deny its wealth. Of course, falling into the hands of Rodriguez, what these found religious icons become are object and subject for discourse on the enterprise of religion and faith, sacredness and everything it represents, tied together by structure and image that are familiar. What works here more than anything is the attention to detail, which must begin with the decision at details that are pertinent to the discussion at hand. The dirtied and dismembered Christ child icons are encased in a miniature cathedral that’s layered with symbols of violence (toy guns and soldiers) and sin (serpents). The whole structure stands, the floor is filled, with plastic toy centipedes, which in this number and context resonate as symbolic of instability and ruin, if not just the venomous and evil that’s here. Entitled “Annuit Coeptis,” which literally translates to "He approves of the undertakings," with a rendering of the Eye of Providence or what’s considered as the “All-seeing eye of God,” here is work that points a finger at the ways in which this Catholic faith allows for evil, and is actually an enterprise that’s complicit in these forms of violence. Though probably what astounds more, what could be the bigger work here, are Rodriguez’s untitled series of pen and ink works, all only lettered for classification purposes, and all revealing the same attention to detail that’s in the bigger installation, and all working from it, maybe off it, if not against it, too.  Of the five pen and ink works on paper, three are portraits, unconventional as these are: all heads, with only mouths visible, all seeming to have grown from the ground like tree trunks with no leaves, all cyborg-like with tubes that connect the body to elsewhere beyond the canvas. Covering the eyes and making up the heads of these portraits are statements on notions of faith, if not the things we genuflect to. The saddest of portraits has pursed lips, closed eyes, top of the head filled with fingers raised up to the sky, where the eye of providence is drawn. The one with mouth agape has a crown down to its nose, and making up all of its head, where power is that which also blinds, which must also mean speech in mid-sentence, always in the process of articulation, of being misunderstood, if not silenced. Another portrait has the mouth open in a scream, as if in pain, maybe in anger. This one is without tubes, but its head is filled higher than the other two, up to the top edge, with tangled thorns interwoven with tubes and machine parts. The weight it carries is far heavier than the other two. And yet, at the same time, it would seem the weight is ours to bear. The sadness and pain in these images speak of a suffering that is sadly familiar, where genuflection is not just about religiosity anymore, as it is about what we fill our heads with, what it is we allow to blind us, what are in our empty screams. The pen and ink work of a body, as if attached to an invisible cross, is pierced with six tubes that enter one side of the torso and come out in the other. Where its stomach should be is a TV set; the pelvis evolves into plant-like creatures that symmetrically fill the sides of the paper. The man’s eyes are closed, his face weary more than anything else. Rodriguez’s drawing of a hand in a religious gesture, with an eye in its palm, is the one pen and ink work with some color: a pink circle behind the hand is a halo of sorts, one that drips and is imperfect, which contrasts sharply with the blood red border and color on the page. Where the wrist should be are gears that render the hand itself, and its symbols of worship, as machine.

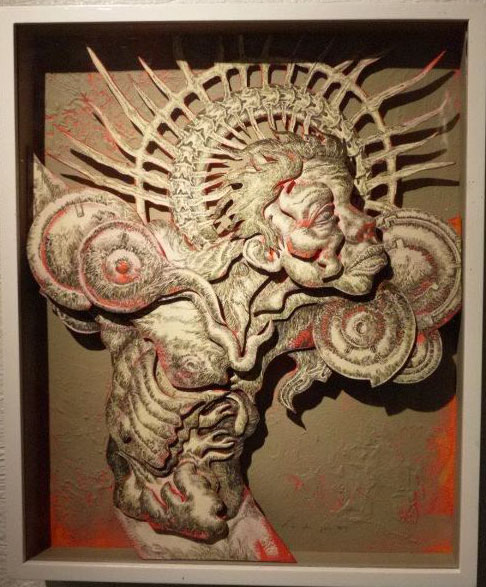

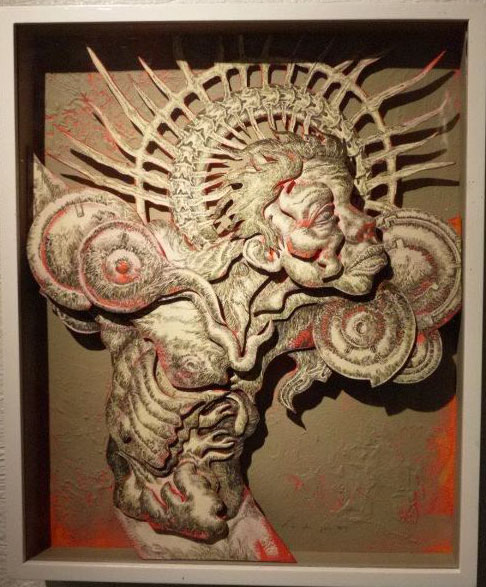

Of the five pen and ink works on paper, three are portraits, unconventional as these are: all heads, with only mouths visible, all seeming to have grown from the ground like tree trunks with no leaves, all cyborg-like with tubes that connect the body to elsewhere beyond the canvas. Covering the eyes and making up the heads of these portraits are statements on notions of faith, if not the things we genuflect to. The saddest of portraits has pursed lips, closed eyes, top of the head filled with fingers raised up to the sky, where the eye of providence is drawn. The one with mouth agape has a crown down to its nose, and making up all of its head, where power is that which also blinds, which must also mean speech in mid-sentence, always in the process of articulation, of being misunderstood, if not silenced. Another portrait has the mouth open in a scream, as if in pain, maybe in anger. This one is without tubes, but its head is filled higher than the other two, up to the top edge, with tangled thorns interwoven with tubes and machine parts. The weight it carries is far heavier than the other two. And yet, at the same time, it would seem the weight is ours to bear. The sadness and pain in these images speak of a suffering that is sadly familiar, where genuflection is not just about religiosity anymore, as it is about what we fill our heads with, what it is we allow to blind us, what are in our empty screams. The pen and ink work of a body, as if attached to an invisible cross, is pierced with six tubes that enter one side of the torso and come out in the other. Where its stomach should be is a TV set; the pelvis evolves into plant-like creatures that symmetrically fill the sides of the paper. The man’s eyes are closed, his face weary more than anything else. Rodriguez’s drawing of a hand in a religious gesture, with an eye in its palm, is the one pen and ink work with some color: a pink circle behind the hand is a halo of sorts, one that drips and is imperfect, which contrasts sharply with the blood red border and color on the page. Where the wrist should be are gears that render the hand itself, and its symbols of worship, as machine.  The other work in “Genuflect” that uses some red is one that isn’t simply a pen and ink work on paper. Attached to sintra boards, this one is installed as a seemingly layered and three-dimensional imagining. Here is a man carrying some weight on his shoulders, his head surrounded by what looks like a halo of the sun, powerful and scary at the same time, removed from the head but attached to it too, brightness and heat in equal parts. The man’s face is nonchalant, which is to say a hint of sadness, a sense of the weight it carries, exists here. But what’s actually here, in this small stark white space, and across these works in “Genuflect” is not just Rodriguez’s critical perspective and intellectual stance on religiosity and faith, nor is it just this great attention to detail. In fact in this exhibit what resonates is the discipline, the control, the knowing when to stop and how. After all, between the installation and the pen and ink works, a lesser artist would’ve and could’ve gone crazy. But in Rodriguez’s hands there is a sense of taking an image and running as far away with it as possible, and taking it back to where it started to make sure it’s saying what it must. Here one finds that Rodriguez is able to push the spectator into acknowledging those limitations, seeing the control, and finding that anger and discontent can be in the thinnest of lines drawn, its magnitude measurable by the painful patience that must have gone into such detailed work. It’s in this sense that “Genuflect” as such is far bigger than the discourse on religiosity and sacredness as we know it, as it might be discussed vis a vis art and creativity by the mainstream bearers of information and judgments like media. There is much here that echoes powerfully about Pinoy Catholicism of these times, yet (thankfully!) there is nothing here that would be easy, or comfortable enough, for the media to take notice and think: oh my, it’s anti-Catholic. There is nothing here that would merit TV coverage, because there is nothing here that would be as superficial as the notions of religiosity and sacredness that our popular culture lives off. Such is its failure at dealing with art. Such is a measure of our capacity at intelligent discourse about culture. And such is the power of genuflection according to Rodriguez. Because here we are told that the silences we carry are not only painful, but pained. Here we are told that the sacred is not what we think, and our smallness is larger than life. Here we are reminded that in a land of questionable sacredness, given religiosity now constantly failing in the face of close scrutiny, we have lost all reason to genuflect. We are larger than our silences. We are more powerful than we think. – YA, GMA News “Genuflect” by Iggy Rodriguez runs at the Kanto Artist Run Space at The Collective in Malugay, Makati City until May 29, 2012.

The other work in “Genuflect” that uses some red is one that isn’t simply a pen and ink work on paper. Attached to sintra boards, this one is installed as a seemingly layered and three-dimensional imagining. Here is a man carrying some weight on his shoulders, his head surrounded by what looks like a halo of the sun, powerful and scary at the same time, removed from the head but attached to it too, brightness and heat in equal parts. The man’s face is nonchalant, which is to say a hint of sadness, a sense of the weight it carries, exists here. But what’s actually here, in this small stark white space, and across these works in “Genuflect” is not just Rodriguez’s critical perspective and intellectual stance on religiosity and faith, nor is it just this great attention to detail. In fact in this exhibit what resonates is the discipline, the control, the knowing when to stop and how. After all, between the installation and the pen and ink works, a lesser artist would’ve and could’ve gone crazy. But in Rodriguez’s hands there is a sense of taking an image and running as far away with it as possible, and taking it back to where it started to make sure it’s saying what it must. Here one finds that Rodriguez is able to push the spectator into acknowledging those limitations, seeing the control, and finding that anger and discontent can be in the thinnest of lines drawn, its magnitude measurable by the painful patience that must have gone into such detailed work. It’s in this sense that “Genuflect” as such is far bigger than the discourse on religiosity and sacredness as we know it, as it might be discussed vis a vis art and creativity by the mainstream bearers of information and judgments like media. There is much here that echoes powerfully about Pinoy Catholicism of these times, yet (thankfully!) there is nothing here that would be easy, or comfortable enough, for the media to take notice and think: oh my, it’s anti-Catholic. There is nothing here that would merit TV coverage, because there is nothing here that would be as superficial as the notions of religiosity and sacredness that our popular culture lives off. Such is its failure at dealing with art. Such is a measure of our capacity at intelligent discourse about culture. And such is the power of genuflection according to Rodriguez. Because here we are told that the silences we carry are not only painful, but pained. Here we are told that the sacred is not what we think, and our smallness is larger than life. Here we are reminded that in a land of questionable sacredness, given religiosity now constantly failing in the face of close scrutiny, we have lost all reason to genuflect. We are larger than our silences. We are more powerful than we think. – YA, GMA News “Genuflect” by Iggy Rodriguez runs at the Kanto Artist Run Space at The Collective in Malugay, Makati City until May 29, 2012.

Pen and ink on paper mounted on sintra board by Iggy Rodriguez Jasmine Ferrer

Iggy Rodriguez's "Annuit Coeptis" is everything you've wanted to say about the Pinoy Catholic religion, and then some. Jasmine Ferrer

A detail of "Annuit Coeptis."Jasmine Ferrer

More Videos

Most Popular