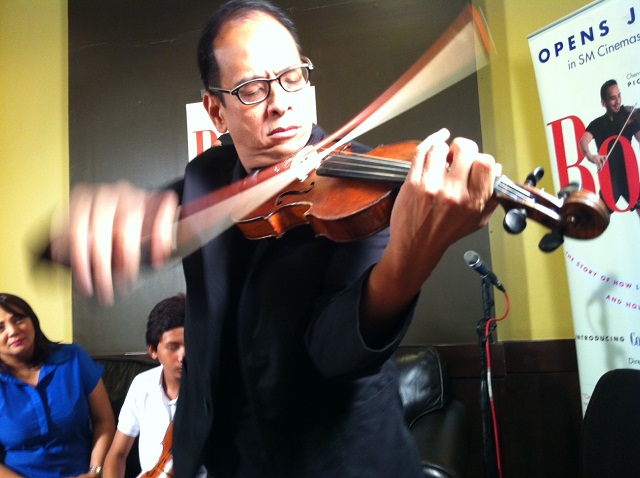

Fridays with violinist Coke Bolipata

It wasn't yet 2 p.m. that one Friday in August when the music from more than 20 violins began to fill the hallway. The weekly three-hour class of renowned violinist Alfonso "Coke" Bolipata with bright-eyed seven- and eight-year-old kids had started earlier than the appointed time, as usual, since the children and their mentor just couldn't wait to start playing.

"Who hasn't played yet?” Coke asked, and a dozen little hands shot up, each child hoping to be called by the teacher.

Coke picked a boy seated in the middle of the room, a small towel sticking out of the back of his shirt. The boy raised his violin, put his chin on the rest, and proceeded to draw his bow across the strings while focusing on the series of notes on the whiteboard.

He sat down as soon as he was done, and after Coke praised him, more little hands went up, volunteering to do a solo.

It has always been like this at the Center for Excellence (Centex) in Tondo, Manila, ever since the after-hours violin class with Coke and his apprentices was started three years ago. These kids, about two dozen of them, were still in kindergarten then. Now they are in Grade Two at the public school run with private sector support, led by Ayala Foundation Inc.

“I've seen them grow. They have all improved,” said Coke.

Asked if anyone of them are gifted, like Julian Duque, Coke's student at Casa San Miguel in Zambales and his co-star in the indie film “Boses,” Coke nodded and said, “Oo, marami. I know it's hard to tell from what you hear. The potential here is really great. And alam na sa preselection pa lang kasi sila mismo, for them to get a scholarship, they have (to pass) an aptitude test for academics. So all of them have a pretty high IQ.”

The kids, who don’t come from privileged backgrounds, are all scholars at this school, so these are the cream of the crop, so to speak. But to get admitted in this music class, they had to hurdle another exam.

“It's more of a proclivity test. They're tested for kinesthetic (skills). There was an aptitude test also, the way they move, the way they listen. Parang the basic functions of eyes, ears, and body,” said Coke. This means the kids are expected to be able to pick up the lessons quickly and read musical notes.

But aside from being smart, the students are also very endearing. Many times that afternoon, Coke joked that they’ll be dismissed soon, and the kids shot back with a resounding, “No!”

“They're very appreciative. I don't know if it's institutional or they're taught to do it, but makita mo, even after (the class), they'll come, ihahatid ka pa sa auto. It's really very heartwarming,” said Coke.

Maybe it's also because it's Coke.

Asked if she knew her teacher is a well-known musician, seven-year-old Pauline G. Baltazar said, “Opo. Ginoogle ko.”

Prodded to say more, Pauline said Coke is “mabait at magaling. Gusto kong aralin ang violin hanggang paglaki ko kasi si Teacher Coke, parang masaya ako 'pag may talent akong ganun.”

Another student, seven-year-old Andriel Norly, said he wants to study the violin “kasi mayroong chance maging katulad ni Teacher Coke na magaling... Napanood ko siya sa TV... Hindi siya nagyayabang. Marunong tsaka mabait.”

Coke as child prodigy

Coke himself started music lessons early since he grew up in a musically-inclined family. At age eight, he began violin lessons with maestro Oscar C. Yatco and had subsequent lessons with Basilio Manalo and Rizalina Buenaventura, according to Bolipata's biography posted on his Facebook page.

He won first prize at the National Music Competitions for Young Artists when he was 12, and not long after, he was enrolled at the world-renowned premiere music school, the Juilliard School of Music in New York.

Of that experience, he told GMA News Online it gave him a “traumatic childhood.”

“It was not smooth sailing for me,” he said. “As a child, it was not good for me to be away from my parents. The idea that you will give up everything, in the '70s it was a different mindset. There are other ways. A slower cook I think is a more healthy recipe. During that time of Cecile Licad, you give up everything talaga for music.”

But he stayed in the US, and was soon playing music everywhere. Name it, he has probably performed in it—whether it’s Carnegie Hall or Kennedy Center, or in major global cities like Frankfurt, Munich, Paris, and even Beijing, Japan, and Indonesia.

A grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington and Artists Affiliates in New York in the early '90s led him to do outreach activities in rural areas in the US.

This got him thinking – if he could do this in America, why can’t he do the same in the Philippines?

And so he returned to the Philippines, and talked to his parents about turning the family property in Zambales, which got burned down, into an arts place, later called Casa San Miguel. He brought in artists who mounted art exhibits, and started the Pundaquit Festival.

In 1996, Coke felt it was time to do more, and decided to turn the place into an arts school for the local community as a social development program. They started offering extension programs in violin taught by Coke, visual arts handled by renowned artist Elmer Borlongan, and music lessons in cello and viola.

“Now, 98 percent of our teachers have trained with us, some since 1996. They started lessons with us, and now they are teaching,” Coke said. Some of them graduated from the Conservatory of Music at the University of Santo Tomas.

Discovering Julian

One of those teachers, who taught Julian Duque, pointed out the boy to Coke. Julian started violin lessons at Casa San Miguel at four years old, and the boy’s talent just shone through.

Coke said Julian got accepted at six years old at an Indiana school, but although he has a scholarship, the boy could not avail of it as he needs more funds to bring his parents there and provide for their living expenses. Julian, now 13, is currently in high school and a scholar at De La Salle Zobel in Alabang.

Right now, four teacher-apprentices who have been trained at Casa San Miguel help teach the kids at Centex in Tondo. Aside from their weekly group class with Coke, the Centex students have a 30-minute individual lesson every week with a violin teacher.

“It’s part of teacher training... We're trying to teach our apprentices in Zambales to do it. We call it ‘playing’ it forward. Since they get it for free, they should pass it on. It's part of our system there that if you're a scholar of Casa, you have to teach six hours a week. Pwedeng three hours in Zambales, three hours in Tondo... In exchange we pay for their tuition fees, allowance, rent,” said Coke.

He said they have a 10-year plan to put up schools in Metro Manila to create more jobs. “It's like what Ryan (Cayabyab) has, Center for Pop. But really more advocacy—less commercial but more advocacy,” he said.

Coke said they are also set to open a Waldorf-inspired preschool at Casa San Miguel this month, “a creativity-based school that’s homegrown.” Residents of San Antonio, Zambales will get a hefty tuition discount as part of the school’s service to the community.

Playing it forward

What drives him to do all these, to split his time between performing and teaching, and inspiring aspiring artists especially among the less privileged? Why do it when he could have stayed in the international arena and be a rock star in the classical music world like Yo-Yo Ma?

“Sa akin, I have always tried to be wholistic in a lot of things. You cannot do one without (the other)," said Coke.

"Parang sa akin, you're not complete with just performing. Nakakapagod din ang performing. With ‘Boses’ we did a whole provincial tour of Cebu, Davao. Performing can get really monotonous and boring," he added. "In America we were doing it worse pa nga eh. We were on a three-month tour, we perform in one city, you sleep, you get up, travel, unpack, perform. Talagang daily grind yon. Nakakasawa. If I could balance it with teaching, with doing music, and doing outreach programs, it won't get so monotonous."

And it’s really about “playing” it forward. “It's passing on a piece of who you are to other people. It's actually not that hard eh. All you need is mentorship, and a real commitment to a student,” he said.

“What music means to me now has a lot to do with how it became part of my life growing up. I want that opportunity to be available to other children,” Coke added.

With that, it was time to go back to his class. The strains of “Bahay Kubo” could soon be heard in the hallway. “Bahay Kubo” on strings? Why not, indeed. It was beautiful. – YA, GMA News