ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

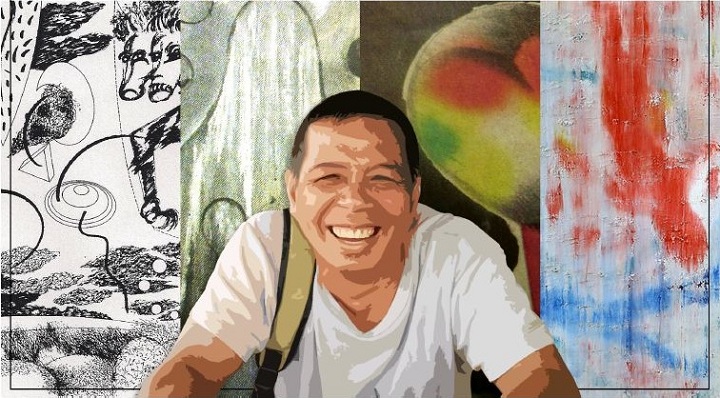

Matchless Modesto talks of sadness, maddening isolation, and art’s power

By FILIPINA LIPPI

Fernando Modesto. Photos courtesy of Eleanor Modesto

In the early part of a career that began in the 70s, his contemporaries could approximate his joyous and delightful images: angels in love, their wings accompanying lovers up in the sky; airplanes soaring above the clouds; abstract art printed with colors springing from his own naked body; curved lines glowing into luxurious petals with a feminine mystique; harlequins unabashedly crying and smiling; turgid tops whirling in the horizon; roots of trees sipping the earth; stars and flowers looking like delectable oysters. Critics compared his works with those of Marc Chagall, the Russian artist who painted unabashed lovers levitating beyond the confines of their room. American-Russian-Jewish avant-garde artist Man Ray was also an early influence.

In a recent exhibit at the West Gallery in Quezon City, Modesto depicted sadness and maddening isolation, the depth of which equals the height of his famous playfulness and robustness when he painted his archetypal “Man Rising” that critics celebrated as endearing and sexy.

Modesto’s piece, “T. S, Eliot,” is a collage containing a dried and brittle twig and a painting of a red figure almost obliterated by blue shadows. It alludes to Eliot’s famous poem, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” which tells a depressing message about ageing, alienation, decay, depreciation, indecisions, paralysis, sadness, and death.

The titles and images of Modesto’s works that are pervaded with Eliot’s gloom are self-explanatory. “Falling Man” is the counterpoise of “rising man”—Modesto’s constant theme in earlier works. “Angels Without Wings” and “St. Michael Looking for Stars” are the opposite of “Angels Conversing with Stars,” done in 1988. He uses palette as a canvas, its hole (meant for the artist’s thumb) projected as a faceless entity. When combined with mirrors, they connote bottomless expectations, unreachable dreams, and unfinished art works—the ironic, ultimate image of man’s fate as seen by Modesto. Indeed, his old images about irrepressible “younging” have disappeared, replaced by figures replete with wrinkles and lines. Carving them with brushes that seem like scalpels and swords, his new images reflect the disembowelment of an artist who used to be the shining warrior of energy and life.

Modesto’s new genre: coming to terms with man’s loneliness

'Match'

It is a holdover of Modesto’s quintessential spirit. It declares the attitude that art or creativity has power—it is the final medium of redemption from a life of drudgery, limitations, and pain. It reiterates an old saying that when an artist creates, no one can hurt him or touch his uncompromised world.

“I paint ideas,” Modesto says. “My images come out naturally and fast, but they have a long history…they are not just images for images’ sake [like the ones] one finds on television—seen once, and quickly forgotten because they are without depth.”

Self-referred contemporary icons

'Holy Smoke'

Modesto’s choices of rare contemporary artistic idols are not objective cast of their innate qualities: they are self-referred—his choices that mirror him, his rarity and idiosyncracies. Dylan has chronicled in songs the anti-war and civil rights rhetoric of his time; Harvey is known for innovative indie, erotic and alternative rock; and Murphy is praised for sad ditties ironically sung in a ringing baritone.

Philosophy of found objects

'Falling Man'

“I used to think a lot about the materiality of material things—one of the visual challenges imposed by my mentor Bobby Chabet,” recalls Modesto. “I used to think of the human body as a good answer, the reason why I was fixated on organ-like images. Then I discovered that inanimate objects, too, can stand alone with emotional impact.” His predilection to plumb emotions through found objects without altering them has remained with him despite his deep-seated fascination for imaginative images on canvas.

Synthesis of the erotic, grounded, and spiritual images

'Angels Without Wings'

“Having a family and children changed and grounded him, but he has remained irrepressible,” explains his wife Eleanor.

“I am also in constant dialogue with poets…my ambition in the past was to be a writer,” confides Modesto, who has covetously adopted poetic titles for his works. The title of a 1981 prize-winning print, “Eleanor’s Satin Horse,” was derived from an Ezra Pound poem.

It should be noted, however, that his new images of sadness and willful redemption (through art), even when they evoke Eliot, are not borrowed: they are life-honed. In 1994, at 42, the artist underwent angioplasty. He suffered a stroke in 2010, when he was 58.

Explaining the title of his new show, he says, “When one is sick, one prays. When one is sick, one is attended to, though sometimes not really minded. One becomes anonymous. No one seems to mind me now [as an artist], but I am happy. I now understand the meaning of freedom.”

From 1986 to 2009, he and Eleanor stayed in Indonesia where she was the head of advertising agency Lintas Jakarta. They have two children: social media manager Paula, 28, and saxophone player Roxanne, 27. Five years ago, they returned to the Philippines, where he is loaded with endless physical therapy and a back-breaking schedule of annual exhibits. — BM, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular