Truth and/as Love: ‘Tisoy Brown: Hari ng Wala’

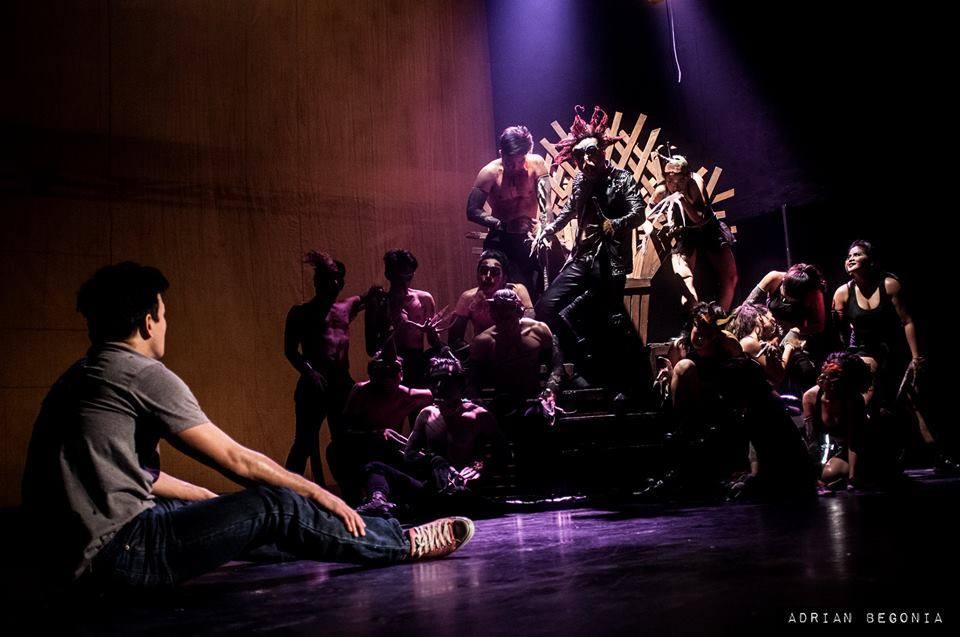

Jose Estrella’s Tisoy Brown: Hari ng Wala recently played at the Wilfrido Maria Guerrero Theater of the University of the Philippines Diliman as the opening piece of Dulaang UP’s current theatrical season.

Fans of this critically acclaimed director’s oeuvre would have easily noticed a difference in this production’s artistic vision: unlike the typically disjointed, phantasmagoric, and visionary “devisings” of her recent work, this new production sees her employing a mostly episodic and straightforward dramatic strategy, following almost earnestly the act-by-act unfolding of Henrik Ibsen’s infamously difficult Peer Gynt, adapted and translated for the Philippine stage by the prolific and extraordinary playwright, Rody Vera.

Watching the play, however, one quickly remembers the fact that the original material is a dramaturgical pastiche that is stylistically incongruous and cinematically interleafed as it is (which is why it has been deemed, by critics, to be a most astonishing theatrical text that was preternaturally ahead of its own time), and that because of this there really is no pedagogical need to aesthetically complicate and devise it any further.

The versified language has of course been chucked in this audibly local and deliberately “banalized” adaptation, as have all the temporal and historically specific allusions in the original. In their place Vera has opted for a locally recognizable set of circumstances: the picaresque hero is still a teller of tall tales, but is now a smart-alecky and slightly oafish Amerasian Juan Tamad or pilandok, who moves from misadventure to misadventure in his quest for self-realization, in the process trampling on the affections of the few people who care about him genuinely, despite his being singularly and patently unlovable.

The bare bones of this plot are of course meant to be entirely reducible to this mythical structure, as Ibsen’s play is quite obviously about the spiritual crisis of his nation during his time, caught as it was between the rational imperatives of individualism on one hand, and the unreasonable and increasingly hopeless nostalgia for its evanescent past, on the other.

We may think of this dynamic as being synonymous with the conflict between the mythologizing imperatives of secularism and religiosity, both. Tisoy Brown, paupered by his particularly anguished situation (biracial, indigent, uneducated, overweight, etc.), understands early on the consolation that the self-championing stories of the hero’s journey must provide, especially given the contrast and the privations of one’s own difficult reality.

In piecing together his most memorable character, Ibsen is said to have drawn from a smattering of Nordic fair tales, although in his critical revisioning of the monomyth the hero proves tragic and almost antiheroic in his mistaken decision to narrativize himself into being by emulating the egotistic ideal that individualism enshrines. This is an inward movement toward rationality that means to supersede and moot spirituality, but in Ibsen’s play it doesn’t, or simply can’t: as the playwright has so acutely determined, it is to the mental asylum that the absolute privileging of the solitary ego must eventually lead, for there can be no subjectivity without the other (which is another way of saying that, at the very least, there can only be intersubjectivity).

In this translation Vera succeeds the most in his hewing faithfully to this theme—that it isn’t the self but rather the other who can verify one’s truth—albeit his decision to “Filipinize” Peer Gynt into Tisoy Brown unwittingly complicates his identity to the point that the premise of the original text may be said to no longer obtain: Gynt’s antiheroic journey and inexorable descent to insanity presupposes a monocultural (Western) ground upon which his identity stands. In this regard it would be useful to remember that this ground’s dissolution into materialism did historically happen on one hand, and it did lead to a continent’s cultural schizophrenia on the other, that orphaned it of the verities—and the ethics—that had shored it up across the centuries, and that consequently led to its wholesale (modernist) rejection of all social and representational norms.

By contrast, the very ambivalence of a character like Tisoy Brown ironically renders him uniquely impervious to this kind of ontological despair, as his very identity always already presumes self-difference: its very “mixedness” is ironically its uncommon source of strength, that suspends it between polarities, and thus enables it to elude categorization. Simply put: Tisoy Brown’s psychoses—metaphorized in this pious text as variations on the idea of the diabolical—couldn’t have been remotely comparable to Gynt’s, since they are a function not of existential alienation (or even of religious cynicism) but rather of the simultaneously heady and harrowing possibilities afforded by the experience of cultural hybridity. In other words, Vera’s adaptation introduces a critical element that it unfortunately doesn’t thematize or conceptually develop: as Amerasian, Tisoy Brown isn’t simply a self, for he embodies a historical otherness that Ibsen couldn’t have foreseen.

In any case, the sentimentally religiose ending—foreordained by Ibsen’s avowed piety—very clearly works in this case, despite Vera’s decision to excise what would have been the hokey reappearance of Gynt’s (here, Tisoy Brown’s) deceased Nanay in the play’s final act. The scene works anyway, because it’s where the play’s donnee is memorably spoken by the good and long-suffering lover, whose selfless devotion is what finally affirms the beloved as true, despite his having narrated and renarrated his egotistical self to the point of existential falsehood (which is to say, of madness).

The exhortation to invest in the other rather than in oneself is of course another way of describing what the most important Christian doctrine—of Charity—decrees, and we do need to say that as a theological virtue it is supposed to supersede even as it must derive from its sister virtue, Hope. As embodied by the competent performances of Tisoy Brown’s cast (excellently headed by the slick and affectingly pudgy Paolo O’Hara, his real-life and feistily earthy mother Peewee O’Hara, and the always wonderful Delphine Buencamino), the journey from reality to truth that the hero undertakes is the same journey that Ibsen’s and Vera’s texts admirably carry out.

While the limit of what is real is what can be experienced, the limit of what is true is what can be envisioned, what can be imagined… This makes truth sound a lot like love, which is also nothing, in the end, if not an act of Faith. As the characters of Tisoy Brown and his devoted and forbearing Maristin (in the original, Solveig) so poignantly illustrate, love is love only if it has no rational basis—which is to say, if it isn't actually earned (or deserved). — BM, GMA News

Dulaang UP's production of "Tisoy Brown: Ang Hari ng Wala" was at the Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater in Palma Hall, UP in February.