A rare evening

What was an activist doing in serenity as the streets began a night-long wailing outside? Truth is, it was difficult choosing the Ayala Museum for my dear friend’s sake.

Patricia and I had already been through a similar upheaval together down EDSA in this country we deeply love. We had also begun earning our full humanity with her younger sister Elvira back then. This path has taken us to forests, caves and mountains inside and outside ourselves for decades.

Now on this very evening of celebrating their father Luis Ma. Araneta’s hundredth year of birth, our nation was in the agony of great dishonor in a stolen state burial for the tyrant we banished three decades ago. Difficult choice: street protest or silent witness?

Choosing, I entered a growing circle of Aranetas and Benitezes with their interrelated clans mingling with apostles of culture, folk dance theater pioneers in the Bayanihan (whose birth Don Luis sponsored) among white-cowled young monks and a maverick historian or two.

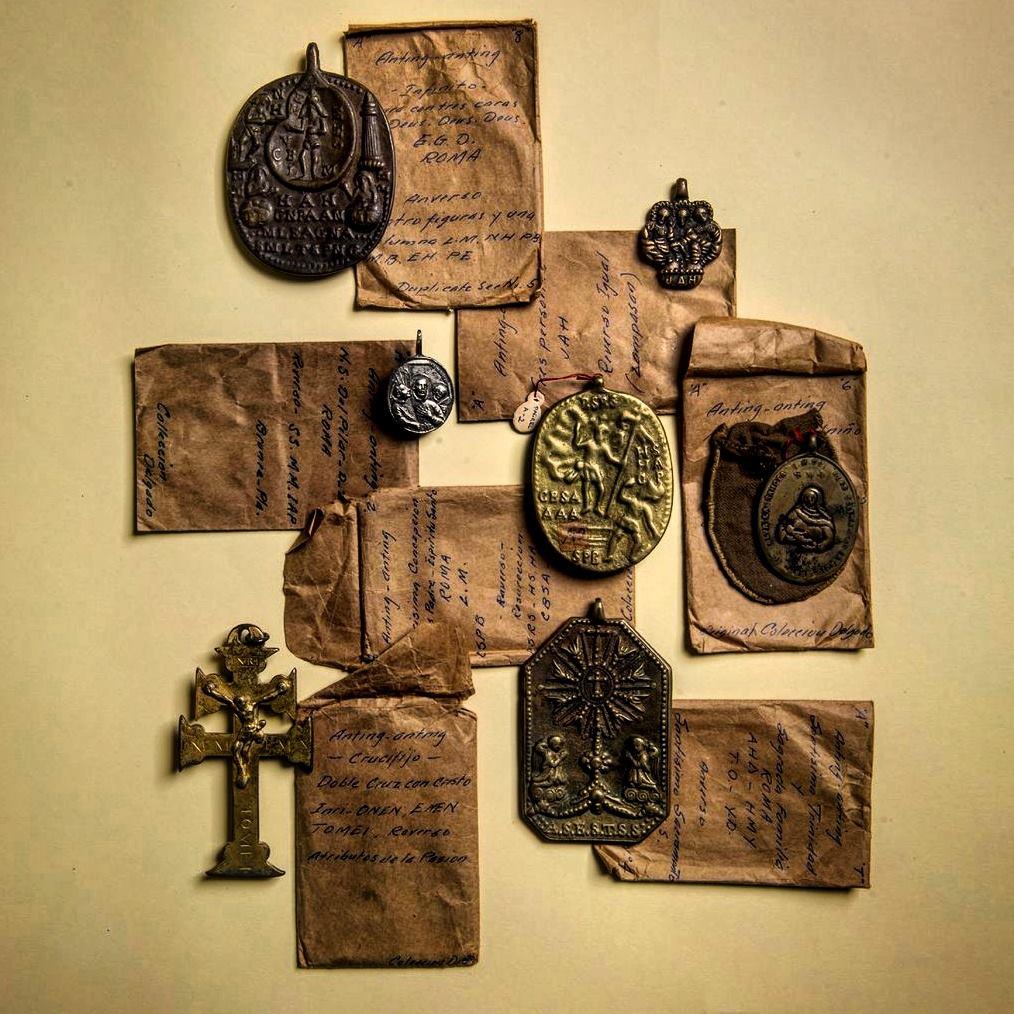

We were gathered “In My Father’s Room,” a book and exhibit of the art and life of the legendary art collector Don Luis. The moment the ribbon was cut on priceless objects, I peered closely at emblems of this man’s lifelong mystical voyage – anting-antings, historic medallions, a handsomely-bound Pasyon (the passion and death of Jesus Christ still chanted today on Holy Week by folk heirs of the mid 19th century religious rebel Manong Pule), and exquisite religious icons carved by animist soul meeting Christianity.

Soul! That was it! That’s what binds Don Luis to the Filipino people forever. I stared again at his formal portrait by the Chilean hyper-realist Claudio Bravo that I’d gotten used to on many visits to his daughters. He sits, a calm scholar in toga with small objects he himself chose to pose with, his hand resting on the Pasyon. What a contrast to that striking black-and-white candid shot of him in our parliament of the streets.

Here he wears a priceless silver-encrusted salakot that historians know to be a symbol of indio nobility, smiling shyly, walking with his cane alongside the “Ibagsak!” crowds. Never mind that he loved his new daughter-in-law Irene, the tyrant Marcos’s daughter, too. How to understand this contrast without Don Luis’s own daughters telling us more?

Only when I helped Patricia edit this book did I read a letter her father wrote and an anecdote he share with an old friend, about a phrase he scratched on the wall of his prison cell, did I finally know that this high-born man was imprisoned in Fort Santiago for his guerrilla work against the Japanese, too. His Spanish words on that priceless lesson of adversity whispered in my ear that evening with his blood kin and kindred spirits in a circle of warmth.

To me, much of the warmth radiated from his own daughters’ recollections of their “life with father.” Here their very private family bares their souls in a book at a time when so many are blinded by bared flesh instead. This family shares meals, debating political flashpoints, pointing the way as each one sees it, sometimes merely tolerate the other’s opposing point of view while always affectionately watching the other grow at their own pace.

What luck that father himself was learning from them. He made it so easy to learn from him, too – a single parent to three children abandoned by their mother. Here, in his daughters’ words, is what he taught them: kindness, generosity, love for art at par with scholarly devotion to Philippine history, love for family, and above all, passion for justice and equity in the Light of Faith.

So rich are these two sisters’ memories that when Patricia invited her old friend Floy Quintos to do a monograph on her father’s ivory pieces, this poet/playwright instantly saw that their memories and reflections were very much part of the story. And so the monograph became a book, with the multi-talented visual artist Karl Castro as designer of both book and exhibit. Visions blended; the whole thing flowed in art, in life.

This monograph-turned-book became both an objet d’art and well as handsome guidebook to both art and life. Its well-chosen font, its storytelling rhythm and sharp color reproductions all perfectly match these exquisite ivory icons of Christian saints traveling east when they were caught by the hands of Oriental artists.

Floy and Patricia agreed that ecclesiastical art scholar Esperanza B. Gatbonton, author of “A Heritage of a Saints” should introduce the long history of these ivory icons carved in Goa, Sri Lanka, and the Chinese Parian in Manila’s Old Walled City. Next we learn how European royals fell so in love with these celestial visions, they drove up the price of ivory into the value of “white gold”.

The consequence no one thought of them was the widespread slaughter of elephants for their tusks. Today more and more in the awakened world condemns this continued slaughter, but prices are still rising while human greed and vanity deny the animal kingdom’s equal right to life.

The good news: You don’t have to own these icons to revel in sheer beauty – in delicate curves of saintly necks, those sinuous slopes of the Virgin’s shoulder, the heart-melting drowsy eyes of the Holy Child falling asleep. They’re in the book.

Patricia’s deep love and respect for her father wears his eyes as she finds the way to share his legacy more and more widely. Not the least of it is how Don Luis broke boundaries of time and place to gather all these treasures together in his lifetime, then towards the end, donated most of them to the San Agustin Museum, now a World Heritage Site. That he did so in his own children’s name for all Filipino children to come was the final gesture of a truly elegant soul.

His eldest daughter followed suit when she invited the Agustinian fathers to lend their museum’s name to the book along with the ivory pieces she chose to exhibit in another museum. This in turn inspired the Ayala Museum’s director Mariles Gustilo to waive rental fees for this special exhibit throughout the long Filipino Christmas season until Jan.29, 2017.

Everything takes money in a cash economy. But this energy from the Araneta father and daughters is contagious, rare and far more precious. I break my own boundary as a journalist sworn to detached objectivity now to highly recommend defying traffic for this taste of heaven in hell.

What that rare evening made clear is this: the Lord of History makes serenity and agony one in a nation whose living and departed continue voyaging together in time into eternity. — BM, GMA News

"In My Father’s Room: Stories and Small Things Near and Dear to Luis Ma. Araneta" is on exhibit at Ayala Museum in its Ground-Floor Galleries through January 29, 2017.

Ayala Museum's Ground Floor Galleries are open Tuesdays-Sundays, from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. The museum is on Makati Avenue corner De La Rosa Street, Greenbelt Park, Makati City.