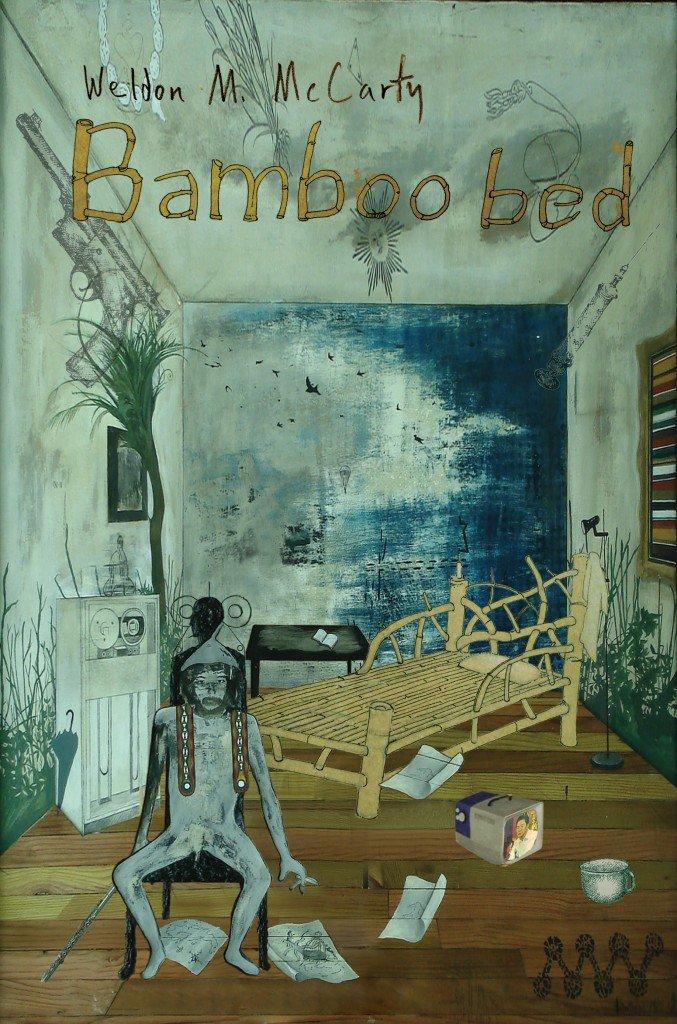

He’s home, part 2: Weldon M. McCarty’s ‘The Bamboo Bed’

Read Part 1 of Sylvia L. Mayuga's article here.

Yuji Izaki of “Sampaguita and Gold Button” emerged from the highly ritualized Oriental culture centuries old in the Japanese archipelago. Weldon M. McCarty, the bright adopted son of a Texan family, emerged from the loosely woven immigrant tapestry of continental America.

Both their “strong” countries compelled their young to war, however. The fictional Yuji obeyed with a ceremonial bow. Real-life Mac, as detailed in his autobiography “The Bamboo Bed,” went the opposite direction—a citizen not quite of America nor even of this world, but of Life itself. Resigned to the fact that America “would always have a war somewhere,” Mac joined the Air Force instead of waiting to be drafted, gambling to avoid shooting it out in the infantry.

♦

But what Mac really wanted was to get “as far away from Texas” as possible. The Philippines was his first choice. His book records his youthful psychodrama played out in the sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll subculture of Manila, Baguio and Pampanga—good and bad swirling like a disco ball, a microcosm of the larger psychodrama of our generation.

Trigger to this psychodrama was the communism vs. “democracy” that transported young Mac to Clark Air Base to help “save” Vietnam from the communist Viet Cong.

Trained to repair and maintain cryptograph machines, he turned into a human cog of a giant war machine. But this writer/musician born subversive was beyond the pale of the powers-that-be. Worse, the same blind spot had Marcos declaring martial law to quash the new Communist Party of the Philippines soon after Mac arrived.

But here was luck. His arrival coincided with a moment of sharp polarization between the militarist status quo and a new global generation’s stubborn refusal to live this way. Instantly recognizable to one another, music became a generation’s sign language, peace signs and prayer beads their emblems, “mind-bending” drugs their communion all over the world.

There was more to this upside of a young American’s fate in the Philippines. It started when the lovely cone of Mt. Arayat beckoned to him from the distance of Clark Field. Finally getting there on holiday by jeep, bus and foot was his “true arrival in the Philippines,” writes this long-time camper.

“There was a chilly little pool among the rocks, a place to win free of the dust of the grassy foothills. On the first night, in the resort-like atmosphere of the TDY barracks, I touched something of the spirit of the place and later in the plaza downtown, found that spirit in a different form. But here in the sheltered beauty and rich fecundity of my little stream-side camp, I was at last overtaken by the numinous power that would make the Philippines forever the home of my heart.”

But the Philippines was more. Its natives also happened to make music of all genres and levels of refinement. Musician Mac was home. He took to Filipinos like a native—jamming with a never-ending stream of brown “music freaks,” alternately meditating and risking life dealing in illegal marijuana. Hawks killed. Doves got stoned, painted, made music, made love.

With them he experimented with different musical instruments, finally settling on the flute. Meanwhile he was going deeper and deeper into his inner world with drugs. Of course, painful lessons descended—jail time on base for daring to express his political views in an army newspaper, then going AWOL.

But those temporary breaches of his freedom were nothing compared to the “monkey” now on his back: heroin addiction acquired in the Philippines, wrecking his health, depriving him of freedom worse than jail or war. More dead than alive, Mac burns in the pain of withdrawal, purging his system for a whole month of agony on the bamboo bed that gave his book its title. Deciding to “clean out” and write about it years later is a mature artist’s hand extended to the unwary young.

Now it must be said: the LSD and mescaline Mac also ingested are largely not considered physically addictive.

What they did was trigger visions and dreams that artists feed on. Neither was his stock in trade, marijuana, addictive. It’s been proven as medicine for cancer and nervous ailments now. A Philippine government mercilessly slaughtering meth a.k.a. shabu addicts could do worse than listen to ex-addicts like Mac on how to break free from this “poor man’s cocaine.”

That, however, was farthest from Mac’s mind while he lived on his chosen knife edge. He’d entered a drug underworld in and out of prison. Learning prison gang rules while keeping his reflective silence brings him to paradoxical spiritual growth amid society’s “dregs.” What he records of the different sort of human family he found is not everyone’s cup of tea. But it reveals a shadow self yielding insight on the “normal” world’s parallel insanity.

Today this “normal” world’s overworked cops are still badly in need of further education. Its overburdened legal system’s outdated ideas continues to try drug cases it barely understands. Media still sensationalizes, ignorantly spinning facts in great disservice to life itself.

Mac McCarty’s years of experience as an “outsider” back and forth the normal world and its shadow, make him a unique witness to a side of Philippine history too little understood. With no intention to save souls but his own, his memoirs have much to teach Filipinos about their own unnamed struggles for light and belonging in a world awash with drugs pretending to be friends and saviors.

University of the Philippines Press’ publication of “Bamboo Bed” acknowledges this danger. — BM, GMA News

“The Bamboo Bed” by Weldon M. McCarty is available at the UP Press Bookstore on E. delos Santos Street, UP Diliman.