The Japanese charmer who helped Filipinos move on from the war

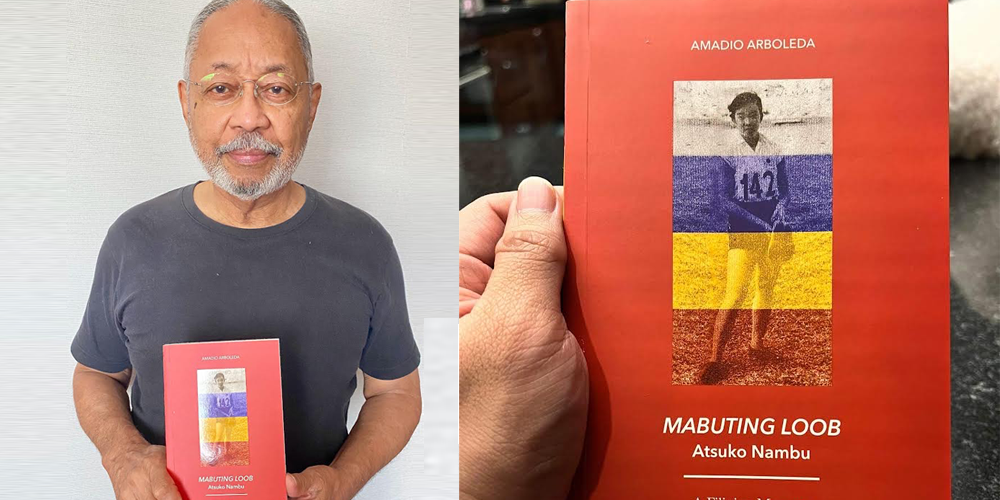

Amadio Arboleda was an Ateneo college junior when he first saw the comely Japanese sprinter Atsuko Nambu at the 1954 Asian Games in Manila.

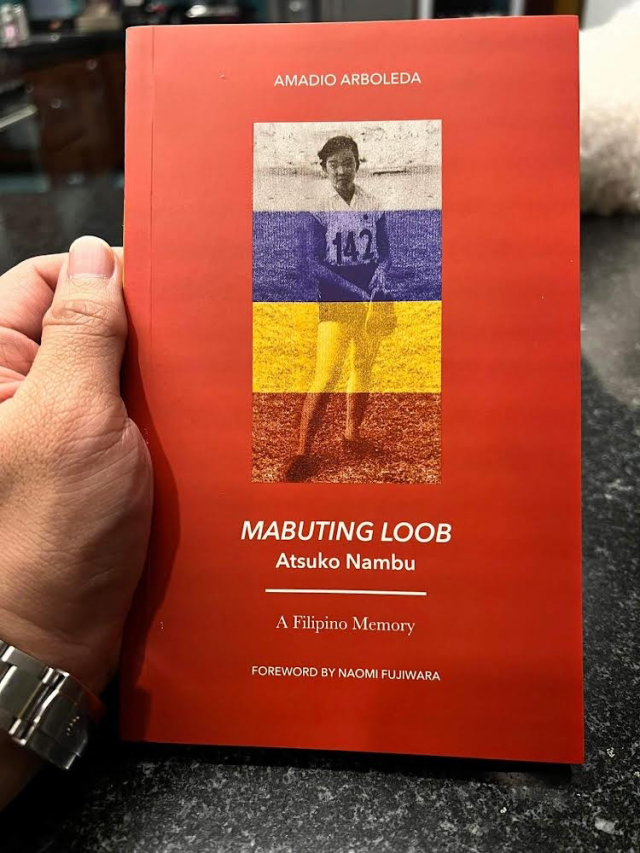

Amadio was smitten, along it seems with a whole generation of Filipino men, and apparently not a few women. From media reports at the time, the celebrated 19 year old from a small town in Japan had captured the hearts of a nation with her beauty, grace, and modesty, even as she was overpowering a field of sinewy rivals from across the continent. Atsuko Nambu won the 100 meters gold medal at the games in an Asian record-setting time.

This book by the 88-year-old Filipino-American writer Arboleda, a longtime resident of Japan, is about his quest for any memories of “the sweetheart” of the Games, now long dead after a car crash that killed her when she was just in her 30s.

Arboleda narrates the stunning twists of this quest in a series of heartfelt letters to the dead Atsuko through the years. That style of storytelling does sound a bit creepy, like the work of an obsessed fanboy gone mad. But his earnest tone and the larger context of his infatuation make this a poignant rather than mushy read.

By itself, a charismatic athlete charming a host country would not be considered historic. But the late teen-age years of both the author and the “crush ng bayan” Atsuko were no ordinary time in history; just nine years before, Manila had suffered the massacre of tens of thousands of civilians at the hands of a rampaging Japanese Imperial Army as it faced defeat in World War 2.

In the months leading up to the 1954 Asian Games, the Philippine and Japanese governments were worried that the appearance in Manila of hundreds of Japanese athletes and their coaches would cause a public uproar, even turning violent, with Filipino spectators nursing fresh war memories.

Much was at stake aside from medals. The two nations were then engaged in delicate negotiations over war reparations. After nearly a decade as a global pariah, Japan wanted to present a benevolent version of itself and be welcomed again into the community of nations. The Philippines aimed to show the world that it had recovered from the ravages of war and could stage a well-organized event as a gracious host.

To the surprise of many, the Asian Games turned out to be a smashing success and enabled both nations to achieve its goals, even creating the atmosphere for an amicable reparations agreement two years later.

The courteous and reserved Japanese delegation — so different from their cruel military compatriots just a decade earlier – was credited for much of that success, even if their athletes embarrassed the host country with their dominant medal haul.

No athlete at the games garnered more attention than the approachable Atsuko Nambu, who established herself as Asia’s fastest woman. Yet accompanying many newspaper reports about her victories were words like “pretty” and “beauteous,” which today would be frowned upon as being sexist in the context of sports, but back then was simply part of the normal exuberance of a pre-feminist time.

In an interview published in a Manila magazine at the time, Atsuko was asked little about sports and instead was peppered with questions about her love life and ideal man. Hers was a gentle, feminine, and even mildly coquettish persona associated with the nation that had recently brutalized Filipinos – that’s what intrigued the author as he aged and saw beyond the blinding effects of youthful hormones. In his effusive narrative, Atsuko Nambu helped an entire nation move on from a traumatic event.

It was emblematic of a promising era for both countries. Japan was on its way to becoming a global economic power, but now under a pacifist Constitution that explicitly renounced war. And the Philippines was led by a youthful President Ramon Magsaysay who was on the cusp of ending the Huk insurgency. The Korean War had ended a year earlier, before it could spread to other parts of Asia.

The Asian Games of 1954 were a watershed moment in an idyllic age that would be short-lived, as the turbulent 1960s approached. The heartwarming cordiality of the event would soon be a distant memory.

Atsuko herself would be mostly forgotten, her track record soon eclipsed by faster Asian women.

But Amadio never forgot. After graduate school in the US, he found himself employed in Japan as the chief editor for an English-language press. The stage seemed set for a dramatic rendezvous. But soon after he arrives in Japan, and before they could meet up, Atsuko dies in a road crash. He is crushed and waits in grief for 18 years before beginning the years of detective work that would yield the pieces of the affectionate portrait in this book.

Obsessions are always hard to fathom. But for many, they’re the reason to get up in the morning, the driving force that gets turned into a book. The author assures us this is not a self-indulgent lark, but a tribute to a significant historical figure, one who was instrumental in making Japan acceptable in a post-war Philippines. In other words, she was much more than the pretty face that launched a thousand Filipino wet dreams.

Yet there could also be a more critical view, casting her as an unwitting Trojan horse for less benevolent forces. Within 25 years, Japanese timber companies would be so welcome, the Philippines willingly suffered among the fastest rates of deforestation the world had ever seen. There seemed little memory of war that could have raised red flags about Japan’s intentions. Did the Asian Games and its Japanese darling help make that war feel even more distant and less consequential? A case can be made after reading this book, with its sentimental recreation of a halcyon 1950s.

“This account is about remembering,” the author writes towards the end of the book. But we can’t remember everything. It is up to each generation to curate what needs to be remembered and determine what weight to assign certain facts in relation to others: who must be remembered more, the invader who bayoneted babies or the teen-age charmer who came after him? Can we not remember both equally? Is that even possible?

And now in the Age of Disinformation, Filipinos are being told to remember events that didn’t even happen and forget horrors that did.

Arboleda at least frequently references the war, even as he was gathering evidence to solidify the legacy of a “rescuing Japanese Joan of Arc.”

A past generation might have wished a transcendent, humanely unifying figure like her had appeared in the previous decade, in the years 1941-45. — LA, GMA News

“Mabuting Loob: Atsuko Nambu” is published and distributed by the Ateneo University Press.